Henry Rowe Schoolcraft

Henry Rowe Schoolcraft wrote the first published account of the Missouri and Arkansas Ozarks. He introduced the region to the world, but his writing helped establish enduring negative stereotypes of the Ozarks and its inhabitants.

Henry was born on March 28, 1793, in Albany County, New York, the son of Lawrence and Margaret Rowe Schoolcraft. His father was an officer in the county militia and superintendent of a glass factory. Schoolcraft received a standard education and, at age thirteen, began working at the glass factory where he learned the trade from his father.

Although Schoolcraft did not attend college, he privately studied mineralogy and geology with Professor Frederick Hall of Middlebury College. Hall praised Schoolcraft’s scientific aptitude, declaring, “I know of no person on this side of the Atlantick, who stand[s] a fairer chance than yourself to become a first rate operative chemist.”

Despite his promise as a chemist, Schoolcraft proved to be unsuccessful as the owner and superintendent of a glassworks in Keene, New Hampshire. By 1817 he declared bankruptcy and sought a fresh start in the West.

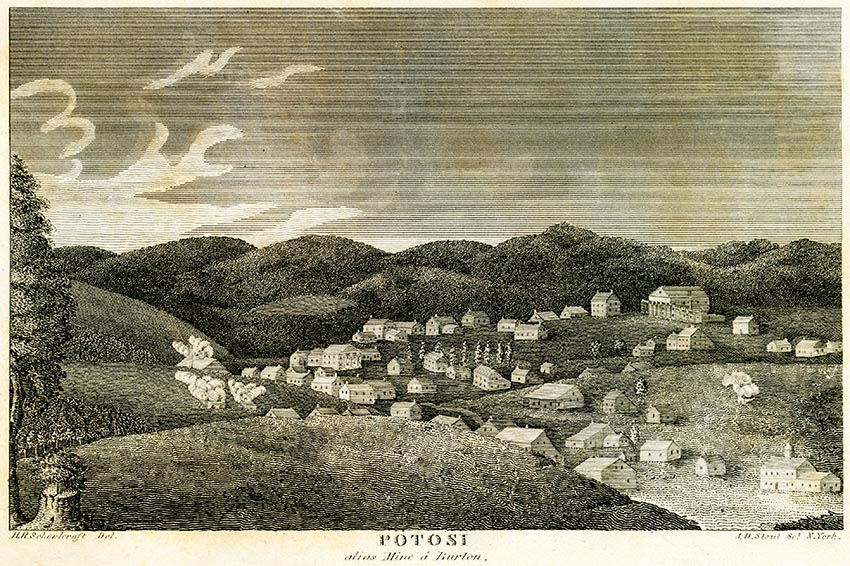

In the summer of 1818 Schoolcraft arrived in Potosi, the heart of Missouri Territory’s lead mining region. Schoolcraft surveyed the area’s mining and smelting operations before he decided to investigate rumors of rich lead deposits in the White River Valley.

He convinced Levi Pettibone, a fellow New Yorker, to accompany him on a three-month, nine-hundred-mile journey through the thinly populated White River Valley region of the Missouri and Arkansas Ozarks during the winter of 1818–1819.

Schoolcraft and Pettibone were poorly prepared when they embarked on their journey. Inexperienced as outdoorsmen, they lacked the proper clothing and equipment for a winter expedition. During the first week of the trip, their packhorse wandered off twice. Later, while they were trying to ford a river, the packhorse plunged into the water, ruining most of their supplies. Schoolcraft and Pettibone found themselves lost without food or dry gunpowder.

Fortunately, the two men met a white hunter named Wells, who, like many of the individuals the duo encountered, generously fed and sheltered them. After buying supplies from Wells, Schoolcraft and Pettibone set out for the James River, a branch of the White River, where they located lead deposits. After conducting tests and recording their findings, they returned from the Ozarks.

Back in Potosi, Schoolcraft quickly wrote and published A View of the Lead Mines of Missouri. He hoped the report would convince government officials to appoint him federal superintendent of the Missouri lead district, but he was instead selected to be the mineralogist and naturalist for the Cass Expedition, which explored Lake Superior and the Upper Mississippi.

In 1821 Schoolcraft published his account of his earlier trip, Journal of a Tour into the Interior of Missouri and Arkansaw. His descriptions of the wildlife, geography, and waterways of the Ozarks introduced the region to readers in the East.

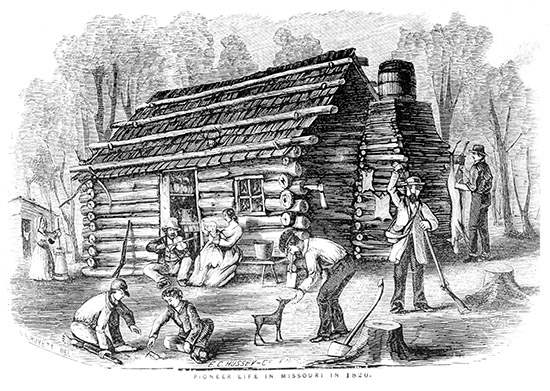

Schoolcraft, however, was less than complimentary of the Ozark’s inhabitants. He was overly critical of their perceived lack of education and rustic, frontier lifestyle. Schoolcraft’s prejudiced account influenced the way that outsiders viewed the people of the Ozarks. He claimed that they had “abandoned the pursuit of agriculture, the foundation of civil society, and embraced the pursuit of hunting, so characteristic of the savage state in all countries.” He neglected to write about the farmers and entrepreneurs he encountered and failed to recognize the independent, self-reliant, adaptive spirit of the early Ozarks frontiersmen and their families. Unfortunately, Schoolcraft’s judgmental views helped establish the lasting popular perception of the Ozarks region as the home of an uneducated and unsophisticated people.

After he left Missouri, Schoolcraft spent the rest of his life as an employee of the federal government. In 1822 he was appointed Indian agent for tribes in the Upper Great Lakes region. The following year he married Jane Johnston, an educated and accomplished woman of Ojibwa and Scots-Irish ancestry. Jane helped Schoolcraft gather and record Native American languages, history, folklore, and customs.

The couple’s first child, William Henry, died at the age of three after contracting croup. The couple had two additional children, Jane Susan Anne and John Johnston Schoolcraft.

In 1832 Schoolcraft led an expedition to Lake Itasca, the source of the headwaters of the Mississippi River, in what is now Minnesota. He published an account of the expedition, Narrative of an Expedition Through the Upper Mississippi to Itasca Lake.

The final years of Schoolcraft’s life were filled with heartbreak. The family’s savings were wiped out during the financial Panic of 1837. A Democrat, Schoolcraft lost his government position in 1841 when President John Tyler, a Whig, was elected to office. The heaviest blow of all came with the sudden death of his wife, Jane, while Schoolcraft was in England.

In 1847 Schoolcraft married Mary Howard, an enslaver from South Carolina. Howard’s dislike of Schoolcraft’s biracial children led to strained relations between the explorer and his children. The following year he suffered a severe stroke, but with the help of his second wife, Schoolcraft published Historical and Statistical Information Respecting the History, Condition and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States in six volumes. Although it was full of useful information, it was poorly organized and not indexed, and thus was not widely used.

After years of declining health and a series of strokes, Henry Rowe Schoolcraft died penniless on December 10, 1864, in Washington, DC. He is buried in the city’s famed Congressional Cemetery.

Text and research by Kimberly Harper

References and Resources

For more information about Henry Rowe Schoolcraft’s life and career, see the following resources:

Society Resources

The following is a selected list of books, articles, and manuscripts about Henry Rowe Schoolcraft in the research centers of The State Historical Society of Missouri. The Society’s call numbers follow the citations in brackets.

Articles from the Missouri Historical Review

- Lange, Lou Ann. “Travelers and Travel’s ‘Significant “Others”’: Three Visitors to the Arkansas Territory in 1818–1819.” v. 100, no. 1 (October 2005), pp. 19–39.

- Luckingham, Brad. “A Note on the Lead Mines of Missouri: Henry R. Schoolcraft to William H. Crawford, 1820.” v. 59, no. 3 (April 1965), pp. 344–348.

Articles from the Newspaper Collection

- “Letter of Henry R. Schoolcraft describing his western travels.” Franklin Missouri Intelligencer. September 25, 1821. p. 1, c. 1. [Reel # 11512]

- “Letters of Henry R. Schoolcraft to Dr. Lewis F. Linn reporting on his geological survey.” St. Louis Missouri Argus. November 11, 1836. p. 3, c. 1. [Reel # 55151]

- “Schoolcraft describes the picturesque country along the source of the Saint Francois River.” St. Louis Missouri Argus. May 31, 1838. p. 1, c. 1. [Reel # 55151]

Books and Articles

- Bremer, Richard G. “Henry Rowe Schoolcraft: Explorer in the Mississippi Valley, 1818–1832.” Wisconsin Magazine of History. v. 66, no. 1 (Autumn 1982), pp. 40–59. [REF 977.5 W75m MICRO 1982–1983, v. 66]

- Christensen, Lawrence O., William E. Foley, Gary R. Kremer, and Kenneth H. Winn, eds. Dictionary of Missouri Biography. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1999. pp. 675–676. [REF F508 D561]

- Conard, Howard L., ed. Encyclopedia of the History of Missouri, Vol. 5. New York: Southern History Company, 1901. p. 503. [REF F550 C743 v. 5]

- Mumford, Jeremy. “Mixed-Race Identity in a Nineteenth-Century Family: The Schoolcrafts of Saulte Ste. Marie, 1824–1827.” Michigan Historical Review. v. 25, no. 1 (Spring 1999), pp. 1–23. [REF 977.4 M5842hr]

- Nigh, Tim, and Larry Houf. “In the Footsteps of Schoolcraft.” Missouri Conservationist. v. 54, no. 5 (May 1993), pp. 9–15. [REF M799 M691m]

Manuscript Collection

- The State Historical Society of Missouri Typescript Collection (C0995)

Item #447 contains papers of Henry R. Schoolcraft, 1819–1822, 1848. Schoolcraft’s correspondence with Stephen F. Austin, Moses Austin, Thomas H. Benton, Rufus Pettibone, and others is included. Originals are located in the Library of Congress and Smithsonian Institution.

Outside Resources

- Library of Congress: Papers of Henry Rowe Schoolcraft

The Library of Congress holds the papers of Henry Rowe Schoolcraft. This link will take visitors to the online finding aid for Schoolcraft’s papers.