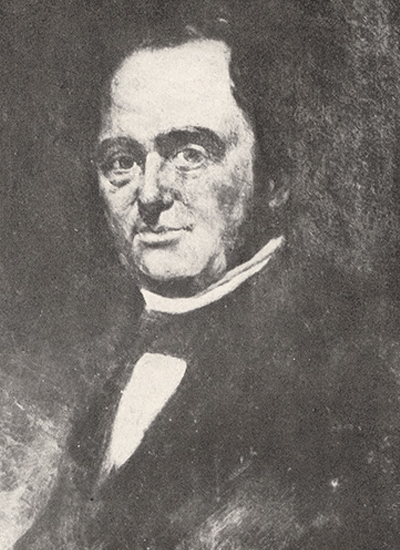

Moses Austin

Introduction

Moses Austin was an American merchant and lead miner who brought national attention to America’s mineral wealth. He built communities on the frontiers of Virginia and Missouri, and laid plans for the colonization of Texas.

Early Years and Education

Moses Austin was born in Durham, Connecticut, on October 4, 1761. He was the youngest of nine children born to Elias Austin and Eunice Phelps Austin. As a child, Moses attended Durham’s small community schoolhouse. Although his formal education was limited, he developed a love of books. Both of his parents died by the time he was fifteen. Afterward, Austin moved to Middletown, Connecticut, where his brother Stephen gave him a loan to start a merchant shop.

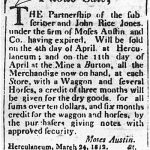

As a merchant, Moses Austin learned how to judge the value of trade items and began the lifelong practice of buying and selling on credit, since cash was often hard to come by at this time. In 1783 Moses started a shop near Stephen’s business in Philadelphia. There he fell in love with Mary Brown (whom he called Maria) and married her on September 28, 1785, after opening a branch of his business in Richmond, Virginia.

Becoming a Miner

“. . . We have reason to flatter ourselves that not only the Interest of this State but the United States in General . . . is interested in the Success of our undertaking.”—Moses and Stephen Austin

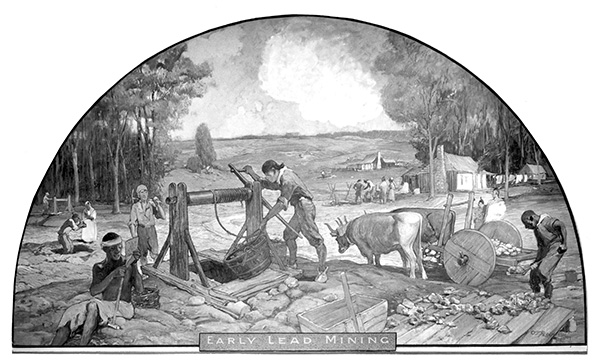

In 1789 Moses and Stephen became partners in a mine on the Virginia frontier. Initially, they were greatly successful. They convinced the U.S. Congress to raise a tax on lead imported from foreign countries, which encouraged people to buy American lead. They also were paid to put a lead roof on the Virginia state capitol building. More good news came in 1793 when Stephen F. Austin, Moses’s son and brother Stephen’s namesake, was born.

Moses and his brother bought the land around their mine in order to expand the business, built a town for their workers called Austinville, and spent a lot on transportation improvements. This expansion caused debt, which worsened when the Virginia capitol roofing project failed. In 1794 they tried to sell the mine but could not find a buyer. Around this time, Moses read an account of the vast mining potential of Spain’s Louisiana Territory and started planning a trip after his daughter, Emily, was born in 1795.

Moving to Missouri

“Notwithstanding the Unpleasent Situation I was in, I could not but be charmed with the Country I had pass.d.”—Moses Austin

On December 8, 1796, Moses Austin and one of his workers set out on a two-thousand-mile round-trip journey through pristine wilderness to what is now southeast Missouri. As they approached the Mississippi River, they got lost in a huge snowstorm, ran out of food, and ended up sixty miles off course. In Missouri, Austin met John Rice Jones, an American who became his business partner and translator to the territory’s French population, and Commandant François Vallé of Ste. Genevieve, another future business partner, who led Austin to a place with exceptionally rich lead deposits called Mine á Breton. Austin soon made a formal request for this land to the Spanish government.

Shortly after Austin returned to Virginia in March 1797, the price of lead dropped by about half because the Congress lowered its tax on foreign lead. Moses dropped out of his partnership with Stephen, who went bankrupt, and the two had a major falling out over money. After Moses received permission from the Spanish, he left for Missouri in June 1798 with a small group of men, women, children, and enslaved people. After a trip fraught with illness and death, they reached Mine á Breton in October.

Within a year, many buildings were erected, including Austin’s stately mansion, Durham Hall. Unfortunately, the French settlers living in the area disputed Austin’s land claims, and the resulting tension cost him his partnerships with both Vallé and Jones. In 1800 the two sides came to a working agreement concerning land rights, which became official in 1802.

The King of Lead

“No country yet known furnishes greater indications of an inexhaustible quantity of lead mineral, and so easily obtained.”—Moses Austin

Business at the new mine boomed. Austin profited by mining the rich ore, renting land to other miners, and selling merchant goods. He also employed new technologies, like a special machine to wash out impurities and new furnaces which were so efficient that many of the region’s miners paid Austin to smelt their ore for them. Just as he had done in Virginia, Austin continually expanded his mine in Missouri and built transportation links like roads, bridges, and ports. For four straight years, starting in 1805, Austin’s mine produced over 800,000 pounds of lead.

In 1802 about thirty Osage attacked Austin’s settlement. The French settlers refused to help, and Austin, a proud man known for his temper, never forgave them. He found and repaired an old abandoned cannon, which warded off future attacks, but the threat of violence always loomed.

Austin’s son, James Elijah Brown Austin (called Brown), was born in 1803, the same year that the Louisiana Purchase made the region part of the United States. U.S. officials appointed Austin as a judge and sought him out for advice. Soon afterward, John Smith T, a rival jealous of Austin’s land and social position, was given Austin’s judgeship by the corrupt territorial governor and was made a militia leader. He tried to get Austin’s land claims overturned and threatened him with violence. Over the next several years, Smith T and Austin engaged in a constant war of words and a number of lawsuits.

Going for Broke and Going Broke

“I have been so much taken up with my own distresses that I could say nothing on any Other subject…”—Moses Austin

Starting in 1807, Austin experienced a series of financial setbacks. First, the price of lead shot dropped by about 40 percent. Then a large load of Austin’s lead got stuck at the port of New Orleans for over a year because Austin’s agent there committed suicide. Aside from high legal fees from his lawsuits with Smith T, Austin paid his brother Stephen $5,000 to settle old debts. In 1812 another large lead shipment was delayed when it got stuck in a sandbar. The price of lead dropped sharply before it could be recovered.

Austin’s response to these setbacks was to take out loans and expand his businesses. He planned the town of Herculaneum as a port on the Mississippi River, and built a nice home, a store, and a tower to manufacture lead shot there. However, Mine á Breton’s production dropped. Most of the workers left to mine newly discovered lead deposits. The War of 1812 severely disrupted business on the western frontier as well. In 1812 the mine produced about half of its 1808 total. When Maria, Brown, and Emily ran out of money on a trip to Philadelphia in 1811, they had to live off the charity of others for two years because Moses could not afford to bring them home.

Austin attempted to remedy his financial problems by leasing a large number of enslaved people to work in the mines, but this proved too costly and only caused more debt. Moses tried placing Stephen F. in charge of the mine, but it did not help. As a final attempt to change their fortunes, Moses and his son Stephen F. helped start a new bank, called the Bank of St. Louis. Their finances were utterly ruined when the bank failed during the Panic of 1819.

Austin’s inability to pay his enormous debts led to a wave of lawsuits from his creditors. He became so desperate for money that he was willing to sell Mine á Breton for less than one-third of its market value, but still could not find a buyer. On March 11, 1820, Moses Austin was arrested and put in jail for failing to pay his debts. Ten days later, Mine á Breton was seized by the government; eventually it was sold to settle a portion of Austin’s debt.

A New Frontier

“To remain in a Country where I had enjoyed wealth in a state of poverty I could Not submit to.”—Moses Austin

As Austin’s finances collapsed and his social standing declined, he made plans to leave Missouri. On May 12, 1820, Austin sold his lead-shot facility in Herculaneum for $2,000 and used the money for a trip to the Spanish territory of Texas. After making preparations for several months in Arkansas with Stephen F., Moses borrowed a horse and departed in October for Texas with Richmond, who was enslaved by Stephen F. They arrived in late December.

Austin’s petition to the territorial governor was initially rejected. However, he happened to meet up with an old acquaintance, the Baron de Bastrop, a Dutch businessman who had a good relationship with the Spanish government. Bastrop was able to get Austin another meeting with the governor, who finally gave his consent to file Austin’s petition to bring three hundred families to start a settlement in Texas.

On the way back, Austin discovered that a fellow traveler, Jacob Kirkham, was trading in illegal livestock. Kirkham then stranded Moses and Richmond in the wilderness without horses or supplies. That night, Austin survived an attack by a wild panther, but both he and Richmond caught pneumonia during the eight days they went without food and shelter. After finding help at a frontier cabin, Austin was bedridden for weeks. He eventually recovered enough strength to travel, and arrived home on March 23, 1821. Five days later, he found out that Spain had granted his colonization petition.

Death and Legacy

“Tell dear Stephen that it is his dieing fathers last request to prosecute the enterprise he had Commenced . . .”—Moses Austin

Moses Austin never fully recovered from his bout with pneumonia. He overworked himself trying to settle his financial affairs and became so ill that he could not even dismount his horse by himself during a trip to Emily’s house. Austin was bedridden for several days, and on his deathbed, passed the responsibility of colonizing Texas to his son, Stephen F. Austin, who is remembered today as “The Father of Texas.” On June 10, 1821, Moses Austin died. He was still $15,000 in debt. Maria lived in poverty in Herculaneum until her death three years later. Emily had their bodies moved to Potosi in 1831.

Moses Austin was an important businessman and community builder on America’s frontier. He helped found Austinville in Virginia, and Washington County and the cities of Potosi and Herculaneum in Missouri. He improved transportation, trade links, and mining methods in these areas, and brought national attention to their mineral wealth. He also started the process of the colonization of Texas. Many Americans moved to Texas after Austin received permission to colonize, and the territory ended up declaring its independence from Mexico in 1836. Nine years later, Texas became the twenty-eighth state of the United States.

The state of Texas recognizes Moses Austin as an important historical figure. When a Texan undertaker was sent to relocate Austin’s body to the Texas State Cemetery in 1938, the local government of Potosi stopped him. After a legal battle over Austin’s remains, the state of Texas decided instead to honor Austin with a statue in San Antonio the next year. Moses Austin’s grave site in Potosi remains near the spot where his majestic Durham Hall once stood.

Text and research by Todd Barnett

References and Resources

For more information about Moses Austin’s life and career, see the following resources:

Society Resources

The following is a selected list of books, articles, and manuscripts about Moses Austin in the research centers of The State Historical Society of Missouri. The Society’s call numbers follow the citations in brackets.

Articles from the Missouri Historical Review

- Viles, Jonas. “Missouri in 1820.” v. 15, no. 1 (October 1920), pp. 36–52.

- Viles, Jonas. “Population and Extent of Settlement in Missouri before 1804.” v. 5, no. 4 (July 1911), pp. 189–213.

Articles from the Newspaper Collection

- “Missourians Played Leading Roles in the Conquest of the Southwest.” Kansas City Times. February 2, 1935. Supplement D. [Reel # 24040]

- “Settlement of Texas Was Planned in Missouri Town.” Kansas City Journal-Post. October 8, 1922. Magazine section, p. 4. [Reel # 19714]

- “Some Bits of Missouri History.” Clark County Courier. August 17, 1923. p. 3. [Reel # 18580]

Books and Articles

- Austin, Moses. A Memorandum of M. Austin’s Journey from the Lead Mines in County of Wythe in the State of Virginia to the Lead Mines in the Province of Louisiana West of the Mississippi, 1796-1797. N.p., 1900. [REF F516.1 Au77 1900]

- Austin, Moses. A Summary Description of the Lead Mines in Upper Louisiana. City of Washington: A. and G. Way, Printers, 1804. [REF F571 Au77 1900, In Case]

- Cantrell, Gregg. Stephen F. Austin: Empresario of Texas. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999. [REF F508.1 Au77ca]

- Gardner, James Alexander. Lead King: Moses Austin. St. Louis: Sunrise Publishing Co., 1980. [REF F508.1 Au772]

- Garraty, John A., and Mark C. Carnes, eds. “Moses Austin.” American National Biography, v. 1. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999. pp. 766–67. [REF 920 Am37 v. 1]

- Gracy, David B., II. “Moses Austin.” Our Heritage. v. 22, no. 1 (October 1980), pp. 5–11. [REF 929.3 T312sag]

- Gracy, David B. “Moses Austin and the Development of the Missouri Lead Industry.” Gateway Heritage. v. 1, no. 4 (Spring 1981), pp. 42–48. [REF F550 M69gh]

- Gracy, David B. Moses Austin: His Life. San Antonio: Trinity University Press, 1987. [REF F508.1 Au772g]

- Phillips, Charles, and Alan Axelrod, eds. “Moses Austin.” Encyclopedia of the American West, v. 1.New York: Simon & Schuster Macmillan, 1996. p. 117. [REF 978 P541 1996 v. 1]

Manuscript Collection

- Clarence Edward Breckenridge Papers (C1037)

Folder 10 in this collection contains a speech delivered on March 21, 1949, before the U. S. House of Representatives by A. S. J. Carnahan, entitled “Moses Austin and the Lure of Lead.” - James A. Gardner Papers (C3702)

This collection contains an extended, unpublished version of historian James A. Gardner’s biography of Moses Austin, as well as his Master’s thesis and doctoral dissertation on Austin. - Guy Brasfield Park Papers (C0008)

Folder 2086 contains a number of historical summaries of Missourians important to Texas, including Moses Austin. - State Historical Society of Missouri Typescript Collection (C0995)

Item #2 in this collection contains a speech delivered before the Annual Meeting of the Texas Agricultural Workers’ Association, which gives a brief history of the Austin family. Item #147 references major events in the life of the Austin family. Item #393 contains a short summary of Austin’s life from a speech made at the dedication of the Austin-Pitcairn roadside park near Festus, Missouri. Item #447 contains the Henry R. Schoolcraft Papers, which includes Schoolcraft’s correspondence with Moses and Stephen F. Austin. - Ste. Genevieve, Missouri Archives (C3636)

Folder 113 contains images of legal paperwork referring to James Bryan’s (Moses Austin’s son-in-law) administration of Austin’s estate after his death. Folder 304 contains legal papers and handwritten letters from Austin regarding lawsuits with Matthew Mullins, Robert Greer, and Bartholemew Butcher and Michel Butcher. - U. S. Works Projects Administration Historical Records Survey of Missouri (C3551)

Folder 18296 in this collection contains a short survey of Austin’s life and the recollections of someone who lived near Austin’s grave site in Potosi. Folder 21853 includes summaries of court cases decided against Austin concerning debt. Folder 21586 contains legal documents recounting the creation of Washington County. - Washington County (Mo.). Probate Records (R0632)

Volume 1 in this set contains information on several court cases related to settling the estate of Moses Austin after his death. - “The Wythe Lead Mines,” H.A. Buehler, 1917 (C2092)

This manuscript submitted to the Missouri Historical Review gives biographical information about the men, such as Moses Austin and his brother Stephen, who owned or operated the Wythe Lead Mines in Wythe County, Virginia, between 1750 and 1812.

Outside Resources

These links, which open in another window, will take you outside the Society’s website. The Society is not responsible for the content of the following websites:

- Moses and Stephen F. Austin Papers, 1676, 1765-1889

This website provides a description of the Austin Papers at the Briscoe Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin. - The Battle for Moses Austin

Here is a link to the Texas State Cemetery’s account of the battle between the officials of Potosi, Missouri, and the state of Texas over the remains of Moses Austin.