James Buchanan Eads

Introduction

James Buchanan Eads spent his life solving difficult engineering problems that made life on and around the Mississippi River safer and more convenient. Eads created a business that removed dangerous debris and shipwrecks from the river. He also designed an armored steamship that helped the Union seize and maintain control of the Mississippi River during the Civil War. His most important engineering achievement was designing and building the first bridge to cross the Mississippi River at St. Louis. His bridge provided a crucial connection between Missouri and eastern cities.

Early Years and Education

James Buchanan Eads was born on May 23, 1820, in Lawrenceburg, Indiana, to Thomas C. Eads and Ann Buchanan Eads. Thomas Eads worked as a merchant in Lawrenceburg and later in Louisville, Kentucky, when James was a child. Because his business was struggling, Thomas decided to move his family to St. Louis in 1833. Ann traveled ahead of her husband with thirteen-year-old James and his two sisters aboard a steamboat called the Belle West. As the boat approached their destination, alarm bells began to ring, announcing that the Belle West was on fire. The captain managed to steer the steamship to the riverbank, and the Eads family safely disembarked. Their possessions, however, were destroyed when the ship burned and then sank to the bottom of the river.

In St. Louis, James peddled apples around town to help his struggling family. By the winter he realized that selling fresh fruit would not provide him with enough money to last through the year. Soon he found a job running errands for Barrett Williams, who owned a dry goods store. Williams saw that James did not attend school, since his family needed him to earn extra income. Recognizing the boy’s intelligence, Williams opened up his personal library to James. With access to the merchant’s books, James taught himself to solve complex engineering problems.

River Salvage

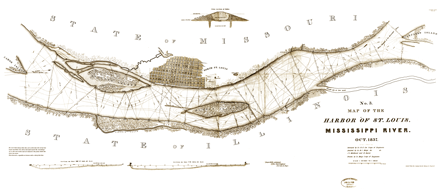

After five years of working for Williams and enjoying the use of his library, Eads took a job on a steamship. While traveling the Mississippi River, he experienced the danger that submerged logs posed to steamships firsthand when his boat, the Knickerbocker, hit a snag and sunk. Though the crew escaped, the boat’s valuable cargo of lead bars sank to the bottom of the river. James began to design a diving bell that would allow a person to work underwater and find lost cargo. At the age of twenty-two, he took his design, which he called a submarine, to a pair of shipbuilders, Calvin Case and William Nelson. The three men went into the river salvage business together based on Eads’s design. Beginning in 1842, their salvage business operated on the Mississippi River from Galena, Illinois, to the Gulf of Mexico. Eads and his company were able to rescue lost freight that included valuable metals and other durable materials.

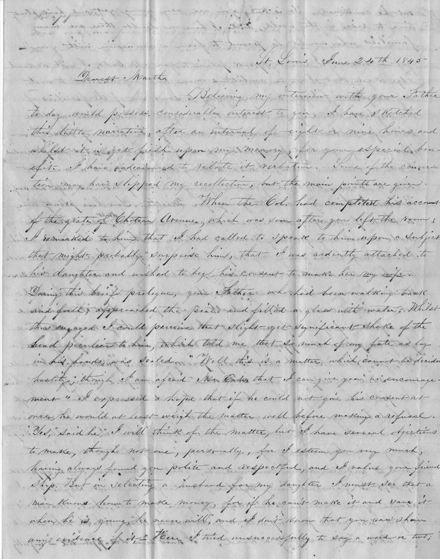

Starting a business made Eads “feel fully competent to support” his sweetheart, Martha Dillon. He wrote to her father, Colonel Patrick Dillon, to ask for permission to marry her. After some difficulty getting Colonel Dillon’s approval, the two were married in St. Louis on October 21, 1845. They had two daughters, Eliza and Mattie. Because he worked on the river, Eads often wrote letters to Martha about interesting experiences away from home. In one, he described an occasion when his workers broke open a sunken ship and casks of bacon surfaced and floated away. Eads and his crew “started for the swinish treasure, after a half mile hard pulling we overtook one cask.”

Armored Steamships

When the United States erupted into civil war, Eads wanted to use his knowledge of the western rivers and his engineering skills to help the Union. In 1861 he wrote to Edward Bates, the US attorney general, to suggest that the Union needed to build a fleet of armored steamships for use on the river. Bates, who was from Missouri, summoned Eads to Washington to make the case for a river navy in the West. Soon after the meeting, the army advertised for bids, and Eads’s design won the contract to build warships. He promised to build seven steamships with iron plating within just sixty-five days. The ships were called “ironclads.”

Because the country was at war, supplies and workers were difficult to find. The first of the gunships, the St. Louis, launched five weeks after Eads started work. Eads failed to build all seven ships in sixty-five days, but after one hundred days the last of the seven entered the Mississippi River. Eads wrote to President Abraham Lincoln that the “St. Louis was the first iron clad built in America…She was the first armored vessel against which the fire of a hostile battery was directed on this continent.” Eads’s ironclads were important in helping the Union to regain control of the Mississippi River. In August 1864, four of Eads’s ships helped defeat Confederate forces in the Battle of Mobile Bay. Armored steamships allowed the Union to resume shipping along the western rivers.

Battle for a Bridge

Eads continued to show his talent for innovation after the war. By that time, railroads were helping to transport people and goods from eastern cities to St. Louis much faster than ever before. Once the train arrived across the Mississippi River from St. Louis, however, the cargo had to be removed and ferried to the city by boat because there was no bridge closer than Rock Island, Illinois, more than 250 miles to the north. Though Eads had devoted much of his life to river travel, he recognized that “truly, these railroads are a great invention!” Not only could trains travel to many places that could not be reached by boat, but they could get there at speeds that steamships on the river could never match.

Following the Civil War, leaders in St. Louis wanted to strengthen the city’s economic outlook. The war had disrupted river-based trade through St. Louis. Meanwhile, Chicago saw its trade increase through growing connections to railroad networks. By the winter of 1866-1867, many St. Louis business leaders had realized that their city was losing control of the region’s economy to Chicago. They believed a railroad bridge would help return St. Louis to prominence as a commercial hub. St. Louis promoters began to make plans for a bridge.

At the same time, the Chicago bridge builder Lucius Boomer convinced Illinois lawmakers to grant him the right to build a bridge for St. Louis. Boomer had close connections to Chicago, and some St. Louisans worried he might try to sabotage the project. Some also remembered that the Gasconade River Bridge, which collapsed in 1855, had been built by Boomer. Like many in St. Louis, Eads lost friends in the bridge disaster, which killed thirty-one passengers on a train that had embarked from St. Louis. Calvin Chase, one of Eads’s river salvage partners, had died in that crash.

Though he had never designed a bridge before, Eads prepared a plan that met the requirements laid out by the legislature. Because the river supported freight shipping, the bridge had to have a central span of five hundred feet to allow large ships to pass beneath it. Eads decided to use steel to achieve this difficult engineering goal. At the time, steel was not commonly used as a building material. Boomer and Eads presented their competing designs before a convention of engineers that Boomer had assembled. Though many of the engineers supported Boomer’s design, the public discovered that he had schemed to manipulate their decision. In January 1868, Boomer conceded the design competition to Eads, leaving the self-taught engineer in control of the project.

Building the Eads Bridge

The use of steel allowed Eads to build a bridge with a central span wide enough for river traffic to safely pass underneath. But Eads also faced another engineering challenge. His knowledge of the river’s strong currents made him realize that the bridge would have to be exceptionally sturdy. Each of the piers holding the bridge above the river had to go deep underground to the bedrock so they would not sink or move. Eads had to devise a plan to sink his brick-and-stone piers through water and ground to a depth of over one hundred feet. He decided to use water-tight structures called caissons from the bottom of the river to the surface. Large pumps removed water from inside the structures. Crews of workers, called submarines, shoveled the sand at the bottom of the river into large pumps. As the workers removed the sand, the piers were slowly lowered into the hole. Curious to witness this feat, hundreds of spectators traveled down the stairs of the caissons to experience the feeling of being underground. The work itself proved to be dangerous; of the six hundred submarines involved in building the caissons, over one hundred got sick from the working conditions, and fourteen died.

A final challenge came with Eads’s choice of steel as the building material. Structural steel had never been used on a project as big as the bridge. Several manufacturers expressed interest in producing the steel, but after seeing Eads’s demanding requirements, many withdrew their bids. The Keystone Bridge Company in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, agreed to produce the steel, but their product did not pass the stress tests designed by Eads and his engineering team. Even after improving the manufacturing techniques, the steel still failed in 10 percent of the tests. Eventually, Eads decided to use chrome steel, which proved easier to work with and became a standard building material in later years. In all, the bridge contained over 13 million pounds of steel, iron, and wood when completed.

A Short-lived Celebration

On July 2, 1874, thousands of people gathered to celebrate the completion of the bridge. Eads planned to provide a demonstration of the strength of his steel structure. In an attempt to promote public confidence, the scientifically minded engineer agreed to an informal test first: an elephant was brought in to cross over from St. Louis to Illinois. People believed that elephants had an ability to know if a structure would collapse. When the elephant stepped onto the bridge without hesitation, the crowd cheered.

Eads also had a bigger demonstration in mind: fourteen locomotives loaded with water and coal to travel back and forth across the bridge. During this show of strength, spectators filled the upper deck from one side of the river to the other. This demonstration succeeded as well. Yet despite the celebration at its opening, the bridge did not immediately improve St. Louis’s economy. Railroad companies initially boycotted the bridge, choosing to ferry their goods across the river in the bridge’s shadow because they owned a substantial share of the Wiggins Ferry Company. Eads’s company therefore went bankrupt a year after the bridge was completed. By the time of his death on March 8, 1887, Eads had not yet seen his bridge become successful. Only in the 1890s would the Terminal Railroad Association of St. Louis manage to fully integrate the bridge into the national network of railroads.

Legacy

James Buchanan Eads used his engineering ability to enhance transportation along and over the Mississippi River. Though he had no formal training, Eads changed the way that large bridges were built by pioneering the use of structural steel. His vision and demanding specifications resulted in a bridge connecting St. Louis to Illinois and the East that continues to stand today. Eads’s activity as an engineer earned him membership in many scientific societies, including the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Text and research by Zachary Dowdle

References and Resources

For more information about James Buchanan Eads’s life and career, see the following resources:

Society Resources

The following is a selected list of books, articles, and manuscripts about James Buchanan Eads in the research centers of The State Historical Society of Missouri. The Society’s call numbers follow the citations in brackets.

Articles from the Missouri Historical Review

- “Missouri Miniatures: James Buchanan Eads.” v. 34, no. 3 (April 1940), pp. 368-373.

- Richardson, Kelli. “Caissons and Calamity: The Tragedy and Triumph of Eads Bridge.” v. 92, no. 1 (October 1997), pp. 18-26.

Articles from the Newspaper Collection

- “The Bridge.” St. Louis Republican. June 15, 1874. p. 8. [Reel # 41463]

- “Building the Bridge: An Important Problem Solved.” Missouri Republican. March 1, 1870. p. 4. [Reel # 41439]

- “James B. Eads.” Missouri Republican. March 11, 1887. p. 6. [Reel # 41525]

Books and Articles

- Christensen, Lawrence O., William E. Foley, Gary R. Kremer, and Kenneth H. Winn, eds. Dictionary of Missouri Biography. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1999. pp. 267-268. [REF F508 D561]

- McHenry, Estill, ed. Addresses and Papers of James B. Eads: Together with a Biographical Sketch. St. Louis: Slawson & Company, 1884. [REF F565.2 Ea25]

- Orrmont, Arthur. James Buchanan Eads: The Man Who Mastered the Mississippi. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1970. [REF F508.1 Ea25or]

- Scott, Quinta, and Howard Smith Miller. The Eads Bridge. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1979. [REF H235.21 Sco85 1999]

Manuscript Collection

- James Buchanan and Martha Nash Dillon Eads Letters (C4189)

This collection contains letters that James and Martha wrote to each other from their courtship in 1844 until her death from cholera in 1852. In addition to discussions about their relationship, James includes much information about his salvage business and travels. - James S. Rollins Papers (C1026)

Includes some correspondence between Eads and Rollins pertaining to the development of railroads and transportation in Missouri and along the Mississippi River.

Outside Resources

These links, which open in another window, will take you outside the Society’s website. The Society is not responsible for the content of the following websites:

- James Buchanan Eads Collection, 1776-1974 (A0427)

The Missouri Historical Society in St. Louis holds a small collection of material concerning James Buchanan Eads, including professional and personal correspondence, as well as news clippings.