Kate Richards O’Hare

Introduction

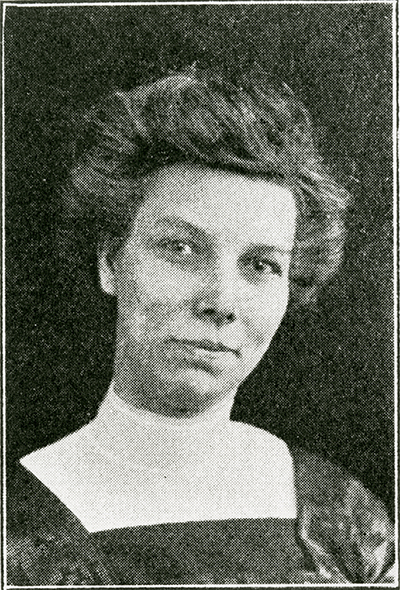

Kate Richards O’Hare was an activist, reformer, and Socialist. She sought to improve the lives of the working class through advocacy and reform. After serving time at the Missouri State Penitentiary, O’Hare became an outspoken critic of the American prison system, calling for better conditions for inmates.

Early Years and Education

Carrie Kathleen “Kate” Richards was born to Andrew and Lucy Sullivan Richards on March 26, 1876, in Ottawa County, Kansas. She was the couple’s first daughter and fourth child. They were a family of farmers.

In 1887 an economic recession followed by a severe drought led the Richards family to sell their Kansas homestead and relocate to Kansas City, Missouri. At the age of eleven, Kate moved from the wide-open prairie to the gritty slums of Kansas City’s West Bottoms. The neighborhood was populated with factories, slaughterhouses, stockyards, warehouses, rail yards, and tenement houses where workers and their families lived in squalid conditions. Andrew Richards found employment, but his salary of nine dollars a week was barely enough to support his family.

Kate later told audiences, “The poverty, the misery, the want, the wan-faced women and hunger pinched children, men trampling the streets by day and begging for a place in the police stations or turning footpads by night, the sordid, grinding, pinching poverty of the workless workers and the frightful, stinging, piercing cold of that winter in Kansas City will always stay with me.”

Kate graduated from Central High School in Kansas City, earned a teaching certificate from Pawnee City Academy in Nebraska, and then briefly taught school.

Joining the Socialist Party

After she quit her job as a schoolteacher, Richards worked at her father’s machine shop as a bookkeeper, but found clerical work boring. She convinced her father to let her work in the shop and found that she enjoyed working as a machinist.

Richards joined the International Association of Machinists and attended union meetings where she debated social and economic issues. After meeting legendary labor activist Mary Harris “Mother” Jones, she joined the Socialist Party in 1901.

Socialism is a political system in which the government operates business and industry on behalf of the people in an effort to create a more equal society. The Socialist Party believed in government ownership of industry, called for public works projects to end unemployment, and favored a shorter work day, increased workplace safety, abolishment of child labor, establishment of a minimum wage, and the creation of a public pension system.

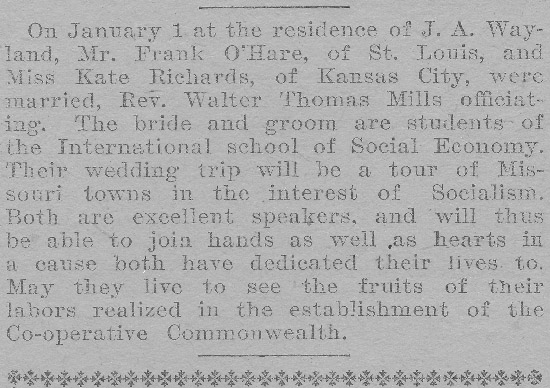

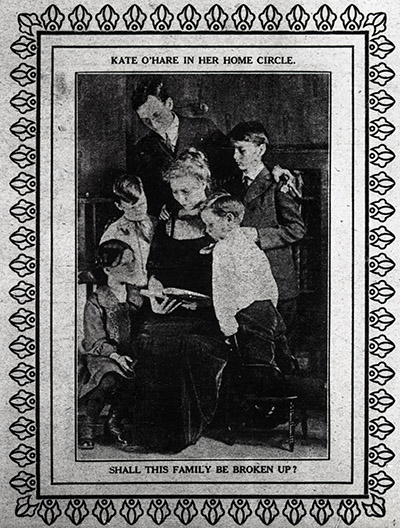

While attending the International School of Socialist Economy in Girard, Kansas, Richards married fellow Socialist Francis P. “Frank” O’Hare on January 1, 1902. They had four children together: Richard, Kathleen, Eugene, and Victor.

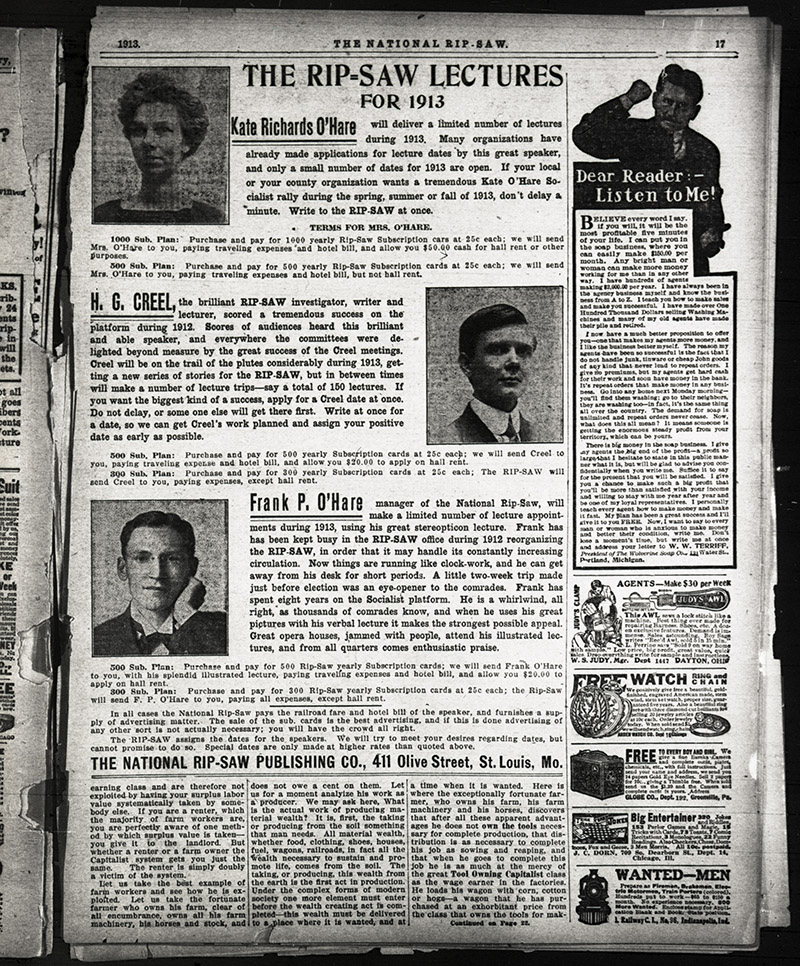

In 1904 the couple moved to Oklahoma Territory, home to many Socialists in this time period. O’Hare became a popular lecturer and author. She gave talks about Socialism across the country and wrote articles for Socialist publications, calling for shorter work days, safer working conditions, women’s suffrage, and an end to child labor.

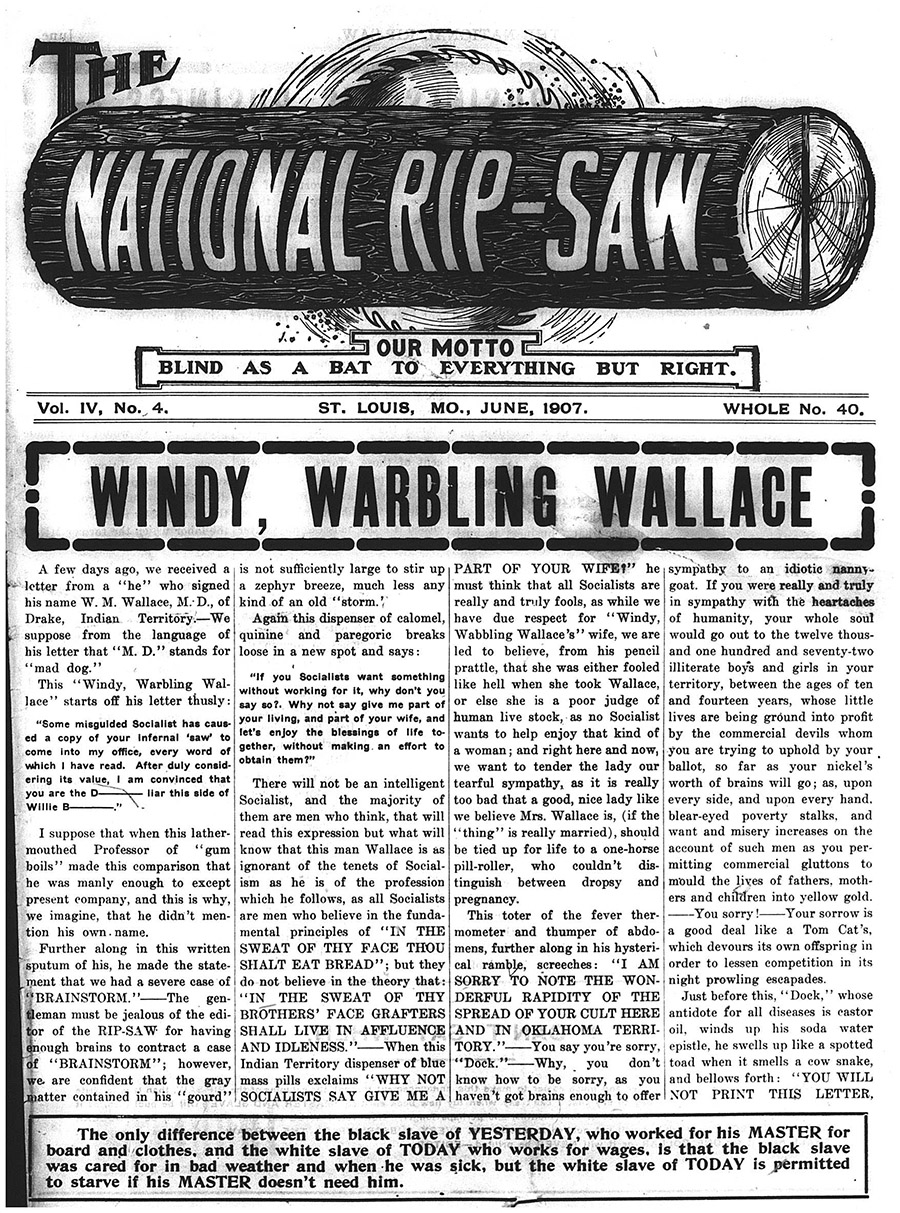

Five years later, the O’Hares moved to Kansas City, Kansas, due to Frank’s poor health and the family’s need for a stable income. In 1910 O’Hare unsuccessfully ran as a Socialist candidate for the U.S. House of Representatives. The following year, O’Hare and her family moved to St. Louis, where she and her husband joined the staff of the National Rip-Saw, a Socialist publication. In 1916 she was nominated as the Socialist Party candidate for the U.S. Senate.

Violating the Espionage Act

During World War I, after delivering a speech deemed to be anti-war, O’Hare was arrested for violating the Espionage Act. She was found guilty and sentenced to five years in prison.

At her sentencing, O’Hare told Judge Martin J. Wade, “It may be that down in the dark, noisome, loathsome hells we call prisons, under our modern prison system, there may be a bigger work for me to do than out on the lecture platform. It may be that down there are things I have sought for all my life … [if] it is necessary for me to become a convict among criminals in order that I may serve my country there, then I am perfectly willing to perform my service there.”

The Missouri State Penitentiary

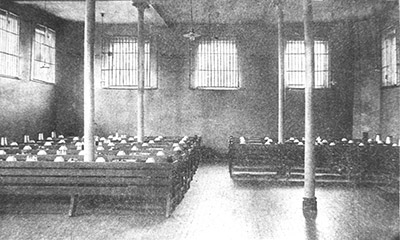

Because the first female-only federal prison did not open until 1927, O’Hare was sent to the Missouri State Penitentiary in Jefferson City as it housed both state and federal prisoners of both genders during this time. The Missouri State Penitentiary was considered “the most wretched and congested prison in the country.”

The conditions that confronted the forty-two-year-old O’Hare were challenging: female prisoners lived in dirty, cramped cells; inmates were forced to remain silent except during recreation hour or else face severe punishment; and prisoners worked five and a half days a week for nine to ten hours a day making clothing in one of the prison’s factories.

In her prison memoir, O’Hare observed, “The average length of a prison term for a woman convict in the Missouri State Penitentiary is about two years and the amount of labor demanded is just about sufficient to wear the average woman out and send her forth a wreck, only fit for the human scrapheap in two years.”

Women who violated prison rules could be placed in solitary confinement or be beaten by guards. Those who fell ill received little to no medical attention.

Dismayed, O’Hare sought to improve prison conditions. Finding many of the women illiterate, O’Hare requested permission to hold night school for fellow inmates, but was denied. She persuaded prison officials to let female inmates use the prison library. After learning an estimated eighty female prisoners shared three bathtubs for bathing with no effort to separate inmates with infectious diseases from healthy ones, O’Hare protested, and additional shower baths were installed.

Reformer

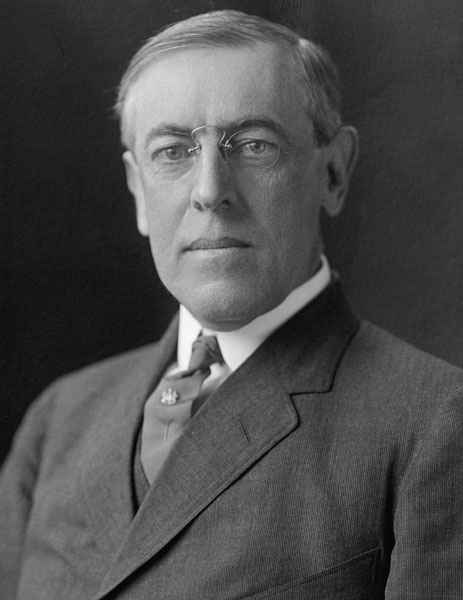

Frank O’Hare, along with others sympathetic to his wife’s situation, repeatedly petitioned the government for Kate Richards O’Hare’s early release. In 1920 President Woodrow Wilson commuted her sentence after she had served fourteen months of her five-year prison sentence.

O’Hare devoted the rest of her life to American prison reform. She published In Prison, a memoir about the wretched conditions she and other female prisoners experienced at the Missouri State Penitentiary.

In 1928 Kate Richards O’Hare and Frank O’Hare divorced. She later married Charles C. Cunningham, an engineer, and moved to California. At the end of her life, O’Hare supported author Upton Sinclair’s ambitious but unsuccessful End Poverty in California (EPIC) movement and served on the staff of U.S. Representative Thomas R. Amlie, a progressive Republican from Wisconsin.

Death and Legacy

O’Hare died of a heart attack on January 11, 1948, at age seventy-one in Benicia, California.

Kate Richards O’Hare was one of the most influential female political figures of her generation. During her lifetime, few men or women could match her political activism on behalf of the working class. She fought to improve the lives of American workers through social, political, and economic reform throughout her career as an activist.

Although not all of the causes O’Hare fought for were adopted, many of the reforms she supported were successful and continue to benefit society to this day, including the eight-hour work day, abolishment of child labor, greater workplace safety, and the establishment of a minimum wage.

Text and research by Kimberly Harper

References and Resources

For more information about Kate Richards O’Hare’s life and career, see the following resources:

Society Resources

The following is a selected list of books, articles, and manuscripts about Kate Richards O’Hare in the research centers of The State Historical Society of Missouri. The Society’s call numbers follow the citations in brackets.

Articles from the Missouri Historical Review

- Stepenoff, Bonnie. “Mother and Teacher as Missouri State Penitentiary Inmates: Goldman and O’Hare, 1917-1920.” v. 85, no. 4 (July 1991), pp. 402-421.

Articles from the Newspaper Collection

- “Kate Richards O’Hare Cunningham Dies; Socialist Crusader Once Lived Here.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. January 12, 1948. p. 8A. [Reel #42780]

Books and Articles

- Basen, Neil K. “Kate Richards O’Hare: The ‘First Lady’ of American Socialism, 1901-1917.” Labor History. v. 21, no. 2 (Spring 1980), pp. 165-199. [REF F508.1 Oh17b]

- Buckingham, Peter H. Rebel against Injustice: The Life of Frank P. O’Hare. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1996. [REF F508.1 Oh175]

- Christensen, Lawrence O., William E. Foley, Gary R. Kremer, and Kenneth H. Winn, eds. Dictionary of Missouri Biography. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1999. pp. 581-582. [REF F508 D561]

- Corbett, Katharine T. In Her Place: A Guide to St. Louis Women’s History. St. Louis: Missouri Historical Society Press, 1999. pp. 173-176. [REF H235.47 C81]

- Dains, Mary K., ed. Show Me Missouri Women: Selected Biographies. Kirksville, MO: Thomas Jefferson University Press, 1989. pp. 226-227. [REF F508 Sh82 v. 2]

- Foner, Philip, and Sally M. Miller, eds. Kate Richards O’Hare: Selected Writings and Speeches. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1982. [REF F508.1 Oh17f]

- Hanley, Marla Martin. “The Children’s Crusade of 1922: Kate O’Hare and the Campaign to Free Radical War Dissenters in the Era of America’s First Red Scare.” Gateway Heritage. v. 10, no. 1 (Summer 1989), pp. 34-43. [REF F550 M69gh]

- Miller, Sally M. From Prairie to Prison: The Life of Social Activist Kate Richards O’Hare. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1993. [REF F508.1 Oh17m]

- O’Hare, Kate Richards. In Prison. St. Louis: Frank P. O’Hare, 1920. [REF 575 Oh1]

- O’Hare, Kate Richards. The Sorrows of Cupid. St. Louis: National Rip-Saw Pub. Co., 1912. [REF F589 Oh14]

- O’Hare, Kate Richards, and Frank P. O’Hare. World Peace: A Spectacle Drama in Three Acts. St. Louis: National Rip-Saw Pub. Co., 1915. [REF F589 Oh14wo]

Manuscript Collection

- Kate Richards O’Hare Letters (C3118)

Kate O’Hare’s letters to her family, April 20, 1919, to April 8, 1920, published in newspapers, and reproduced in book form April 14, 1920. Mrs. O’Hare, a Socialist reformer, wrote the letters from the Missouri State Penitentiary, where she served a fourteen-month term for opposing the draft for World War I. They acknowledge gifts and letters, and discuss the Socialist movement, diseases, prison food, heat and ventilation, and mental disturbances of inmates.