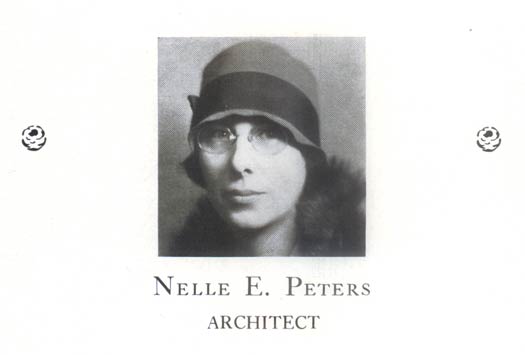

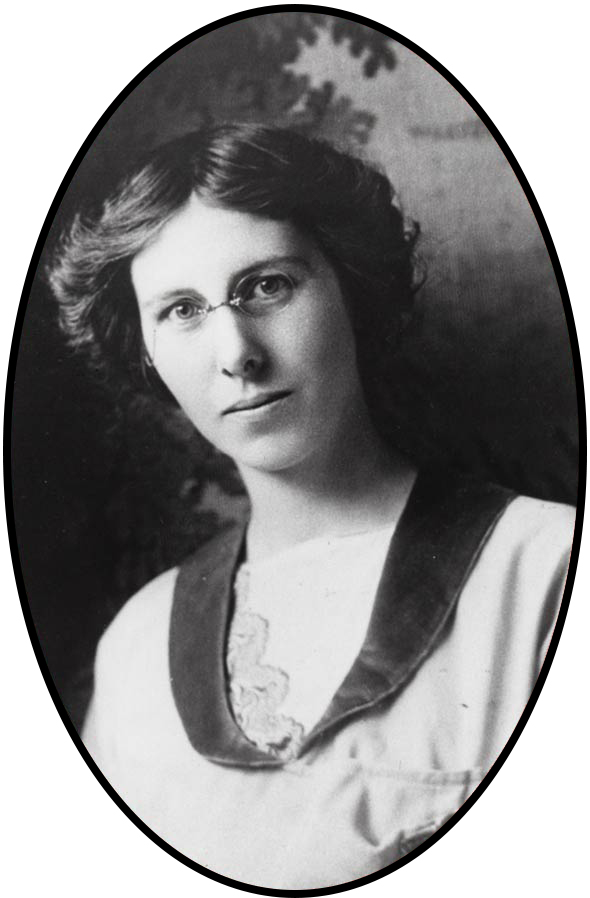

Nelle E. Peters

Introduction

Nelle E. Peters was one of Kansas City’s most productive architects. She designed numerous buildings during the 1920s when she was one of the few women architects to have an independent practice. She specialized in designing apartment buildings and hotels. During her more than sixty years as an architect, Peters designed almost a thousand buildings, mostly in the Kansas City area.

Early Years and Education

Nelle E. Peters was born Nellie Elizabeth Nichols in a sod house in Niagara, North Dakota, on December 11, 1884. Her parents were John and Altha Nichols, and her siblings included Gertrude, Gordon, and John. Reared on a prairie farm, Nellie showed an early talent for drawing and sketching, as well as a love for mathematics, geometry, and algebra. She once told a news reporter, “When I was a child I preferred to draw mechanical things – anything from a bolt with all its threads to a steam engine.” Nellie believed these abilities came from her millwright ancestors.

The Nichols family later moved to Minnesota before settling in Iowa. While not much is known about young Nellie’s early education, she did attend Buena Vista College in Storm Lake, Iowa, from 1899 to 1902. She would have been high school age and studied vocal music at the school’s conservatory. At the time, the college was not officially recognized and did not grant degrees.

After finishing school, Nellie took the advice of her sister and decided to combine her love for math and art by pursuing a career in architecture. Although she lacked formal training, Nichols knew she could do the job. She moved to Sioux City, Iowa, to look for work.

Becoming an Architect

At first, the architectural firms in Sioux City would not hire Nichols. She didn’t give up, however, and went back to offices that had turned her down. Around 1903 her persistence paid off when Frank Colby of Eisentrout, Colby, and Pottenger hired her after making a bet with his partner. Nichols later recalled, “I talked and talked and at last I talked myself into a job.” The firm paid her $3 a week to be a drafter.

During her four-year apprenticeship with the company, Nichols took correspondence courses in architecture to add to the on-the-job training she was receiving. The firm transferred Nichols to their Kansas City branch around 1907, but the lack of work there soon led her to seek outside projects.

Starting Her Own Business

Nichols stayed with Eisentrout, Colby, and Pottenger until about 1909 before she decided to use her “small savings and a large amount of nerve” to set up her own practice in Kansas City. Her office was located at 209 Reliance Building. Nichols’s first works as an independent architect were three small houses, and she charged $15 for each design. Not wanting to appear as a beginner, however, she labeled her first plan No. 25.

In 1911 Nichols married William H. Peters, a design engineer for the Kansas City Terminal Railroad. While Peters continued to work during her marriage, her most productive phase as an architect did not come until after she divorced her husband in 1923. It was also around this time that she began using “Nelle” instead of “Nellie.”

The 1920s and Success

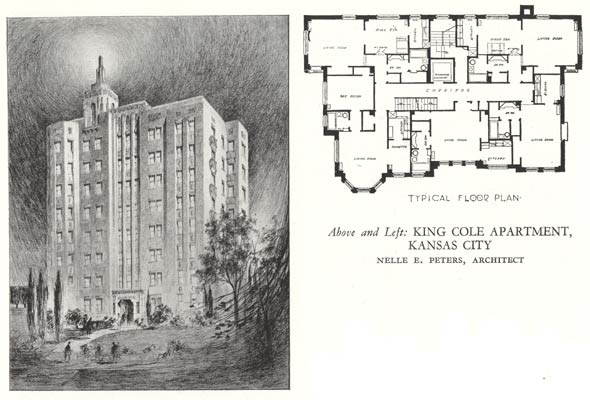

During the 1920s, Nelle E. Peters rapidly became one of Kansas City’s leading architects. Much of this success was due to her partnership with Charles E. Phillips, a local developer. Their business relationship began in 1913, and the association shaped the path of Peters’s career. Throughout the 1920s, Peters designed many hotels and apartment buildings for the Phillips Building Company.

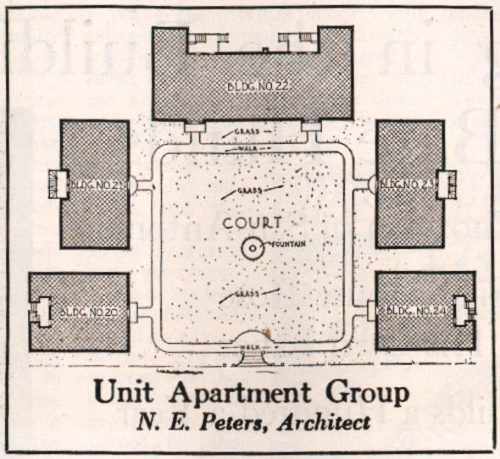

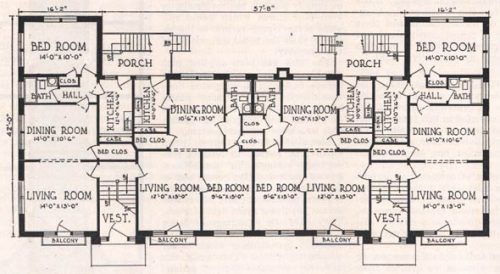

Large apartment complexes constructed around courtyards soon became Peters’s trademark. Her simple designs drew upon Tudor and Spanish Colonial styles, and she favored the use of columns and terra cotta ornaments. She also became known for her efficient use of space in floor plans.

One of Peters’s most well-known sets of apartment buildings is the “literary block,” located on the west side of the Country Club Plaza in Kansas City. Each of the buildings is named after a famous author, including Mark Twain, James Russell Lowell, Robert Louis Stevenson, Washington Irving, Thomas Carlyle, Eugene Field, and Robert Browning.

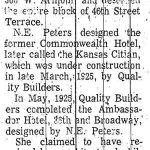

In 1924 Peters completed designs for at least twenty-nine commissions, including the landmark Ambassador Hotel located on Broadway. When it opened the next year, the hotel was the largest in Kansas City and featured a roof garden. Around 1925 Peters set up a new office on the tenth floor of the Orear-Leslie Building.

As Peters built a solid reputation, she also designed apartment buildings for other places in Missouri. In 1927 the Columbia Missourian announced a group of city businessmen would use a design by Peters for a new apartment building near the University of Missouri. The English-style building would have eight apartments on each of its three floors. This building became the Beverly Apartments located on Hitt Street. Later in the year, the same group of investors used another of Peters’s designs and built the Belvedere Apartments across the street. Peters also designed the Bella Vista Apartments in Jefferson City in 1927.

While Peters specialized in designing apartment complexes and hotels, she did not limit herself to them. She also planned single-family homes, office buildings, and churches, as well as at least one hospital. In 1928 Peters did a design for the Kansas City-based Luzier Cosmetics Company, which combined their office and plant. The laboratory’s façade is recognized as one of her most notable designs. When the company acquired the building to its north in 1933, the new section was remodeled to match Peters’s design.

Competing in a Man's Profession

While she may have been one of the few women working as an architect at the time, Nelle E. Peters never saw herself at a disadvantage. During one interview in the 1920s, she talked about working in a man’s profession. One man she designed a building for told her he was surprised to find himself discussing architectural details with a woman. Peters concluded, “All the talk you hear about men not wanting to take instructions from a woman is bunk, I believe.”

One of the reasons Peters had the opportunity to compete and excel as an architect was that the profession was unregulated in Iowa when she began. The profession was also not regulated in either Missouri or Kansas until the 1940s. The lack of regulations in these states meant there were no educational requirements to prevent people from pursuing a career in architecture. This allowed Peters to enter a business otherwise off-limits to most women.

While these circumstances gave Peters the chance to pursue her dream, they did not guarantee success. Her ability to quickly produce high-quality, efficient designs allowed Peters to thrive as an architect in the 1920s. In a 1925 interview with the Kansas City Journal, Peters told a reporter, “I want each building to be as perfect, as economical and practical, as if I were building it for myself.”

The skills Peters developed brought her a lot of work, as well as national attention. In 1930 her work was featured in an Architectural Record article on “the place of the apartment in the modern community.” The article showcased designs by only a handful of Midwestern architects and only one other woman. For Peters to be included was a noteworthy accomplishment.

A Career Fades

While Nelle E. Peters spent almost six decades working as an architect, her career basically ended in the 1930s. During the Great Depression, private construction largely halted across the country. Most of the work available to architects was designing public buildings for the local and federal governments. Since projects like these usually went to much larger firms, Peters saw a sharp decline in work. To make extra money, she did seamstress work, painted china and watercolors, created and sold crossword puzzles, and wrote poetry.

In addition to fewer available projects, Peters faced other setbacks. During the early 1930s, she had a “breakdown” and later became quite ill. For a time, she was unable to walk. Although both she and the economy eventually recovered, Peters never again received the same level or amount of work she had once known.

One of Peters’s last major projects was designing an addition to the Ohio Street Methodist Church in Butler, Missouri. The original structure had been built in 1901, and the church hired Peters to plan an educational wing in 1959. Peters retired in 1965, although she continued to accept small projects that she could complete at home for a short time.

On October 7, 1974, Nelle E. Peters died of heart disease at the age of 89 at the Fairview Nursing Home in Sedalia, Missouri. Her ashes were buried at the Elmwood Cemetery in Kansas City.

Peters's Legacy

Since her death, Nelle E. Peters has received renewed attention for her architectural work. While some of her work has been demolished, many of the buildings she designed still stand. They can be found in historic districts throughout Kansas City, such as the Ambassador Hotel Historic District and the Walnut Street Warehouse and Commercial Historic District.

Two districts in Kansas City have even been named after her, an honor not given to many individuals. In 1982 the city designated a section of buildings at the corner of Summit Avenue and 37th Street as the Nelle E. Peters Historic District. Another section along 48th Street was named the Nelle E. Peters Thematic Historic District in 1989.

With nearly a thousand buildings to her credit, the architectural legacy Peters left behind shaped the appearance of Kansas City, as well as other towns and cities throughout Missouri and the Midwest.

Text and research by Elizabeth E. Engel

References and Resources

For more information about Nelle E. Peters’s life and career, see the following resources:

Society Resources

The following is a selected list of books, articles, and manuscripts about Nelle E. Peters in the research centers of The State Historical Society of Missouri. The Society’s call numbers follow the citations in brackets.

Articles from the Missouri Historical Review

- Ehrlich, George, and Sherry Piland. “The Architectural Career of Nelle Peters.” v. 83, no. 4 (January 1989), pp. 161-176.

Articles from the Newspaper Collection

- “Big Apartment House Planned: Corporation of Columbia Business Men to Build Structure.” Columbia Missourian. March 15, 1927. p. 1, col. 6. [Reel # 7602]

- Blount, Upjohn. “Robert Louis Stevenson: Historic Plaza Living at an Affordable Price.” The Kansas City Star. June 9, 2007. pp. H1, H6. [Reel # 23641]

- “Building Boom in Apartment Houses Here.” Columbia Missourian. December 16, 1927. p. 1. [Reel # 7605]

- Canon, Jill. “Nelle Peters Left Her Stamp on Kansas City.” The Kansas City Star. December 24, 1995. p. K1, K7. [Reel # 22955]

- “Construction Bid Accepted: Kansas City Man to Build Beverly Apartment House.” Columbia Missourian. April 7, 1927. p. 1. [Reel # 7603]

- “Enters Architectural Field Because of Desire for Something Different.” Kansas City Journal. November 21, 1925. p. 7. [Reel # 19265]

- Koppe, George. “Nelle Peters: An Unheralded Architect.” The Kansas City Star. February 8, 1981. p. 2H. [Reel # 22185]

- “Mrs. Nelle E. Peters.” The Kansas City Star. October 12, 1974. p. 10, col. 5. [Reel # 21832]

- Serrano, Richard A. “Historic Building is Razed.” The Kansas City Times. May 7, 1979. p. 1B. [Reel # 22101]

Books and Articles

- “The Amazing Nelle E. Peters.” Preservation Issues: News for the Preservation Community. Missouri Department of Natural Resources, Historic Preservation Program. v. 3, no. 2. pp. 6-7 [REF M 719.32 M691pi]

- Christensen, Lawrence O., William E. Foley, Gary R. Kremer, and Kenneth H. Winn, eds. Dictionary of Missouri Biography. Columbia: Univ. of Missouri Press, 1999. pp. 611-612. [REF F508 D561]

- Dains, Mary K. Show Me Missouri Women: Selected Biographies. Kirksville, Mo.: Thomas Jefferson Univ. Press, 1989. pp. 81-82. [REF F508 Sh82]

- Flynn, Jane Fifield. Kansas City Women of Independent Minds. Kansas City: Fifield Publishing, 1992. pp. 117-118. [REF H128.18 F679]

- Piland, Sherry. “Early Kansas City Architect: A Liberated Woman.” Historic Kansas City News. v. 2, no. 5 (April 1978), p. 8. [REF H128.35 H629]

Manuscript Collection

- Nelle E. Peters Architectural Records (K0041)

These architectural records contain original linen and tissue paper drawings of numerous buildings designed by Nelle E. Peters. The drawings are for apartments and hotels in Kansas City and Jefferson City, Missouri, as well as Tulsa and Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. - Nelle Peters Architecture Photograph Collection (P0180)

Photographs of buildings in Columbia and Jefferson City, Missouri, designed by architect Nelle Peters.

Outside Resources

These links, which open in another window, will take you outside the Society’s website. The Society is not responsible for the content of the following websites:

- Kansas City Register of Historic Places

This website contains a list of historic buildings in Kansas City, including the Nelle E. Peters Historic District and the Nelle E. Peters Thematic Historic District. - Tulsa Foundation for Architecture

This website features an article about Nelle E. Peters and a hotel she designed in Tulsa, Oklahoma.