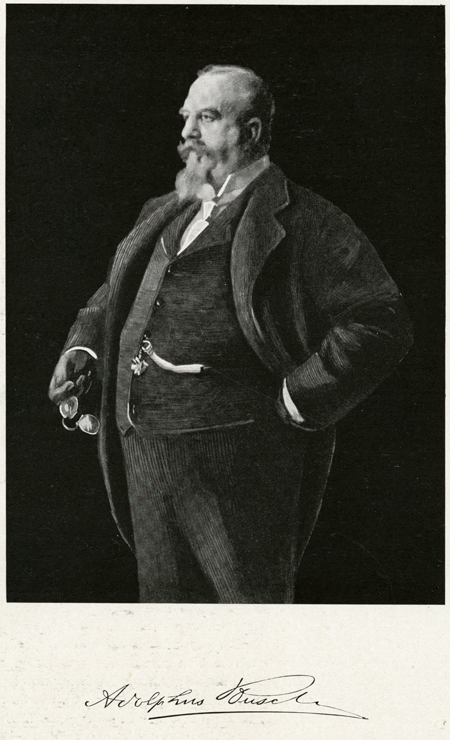

Adolphus Busch

Introduction

Adolphus Busch was a German immigrant who was instrumental in building the Anheuser-Busch Brewing Association in St. Louis, Missouri, into the largest brewery in the United States. He is recognized as one of the most successful businessmen of his era, and is memorable for both his extravagant spending habits and his charitable giving.

Early Life and Education

“The best advice I can give a young man just starting in business life is to work faithfully and loyally and with untiring energy for his employer—to give his employer double what he is paid for.”

–Adolphus Busch

Adolphus Busch was born on July 10, 1839, in Kastel, a small community near Mainz, Germany. He was the twenty-first child born to Ulrich Busch, a successful businessman from Mainz, and the fourteenth with his second wife, Barbara Pfeifer Busch. They provided Adolphus with a first-rate education. He went to the gymnasium in the city of Mainz and the academy at Darmstadt. After this, he studied French at the Collegiate Institute of Brussels, one of the best colleges in Belgium.

Adolphus worked at his father’s lumber yard for a short time, and then went to work for a shipping house in Cologne, a port on the Rhine River in western Germany, where he learned a lot about the river trade. Busch moved to St. Louis in 1857 after hearing many tales about greater business opportunities in America.

Busch was able to put his knowledge of river trading to good use as a clerk in a shipping house. Although he started off cleaning windows and sweeping floors, his hard work and intelligence were noted. He was soon a familiar face along the row of merchant houses on the riverbank known as “Commission Row,” hunting bargains and judging the quality of the merchandise that arrived in the city. He was especially skilled at judging brewing supplies, like hops, malt, and barley, a skill that would come in handy later as a brewer. After his father died, Adolphus inherited a sizeable amount of money from his father’s estate which allowed him to partner with a local merchant to start a trading business, Wattenburg, Busch & Co., in 1859.

Family Ties

“For every man of responsible position there must be ready another to succeed him…”

–Adolphus Busch

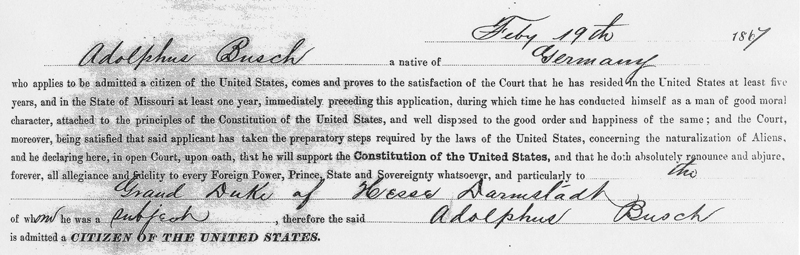

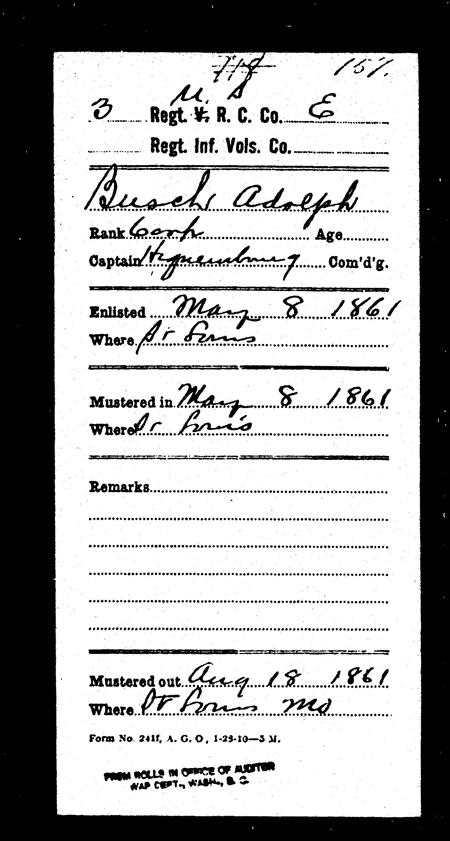

About the same time that Adolphus Busch came to St. Louis, a wealthy soap manufacturer named Eberhard Anheuser purchased a struggling business called the Bavarian Brewery. Anheuser bought brewing supplies from Busch and the two became friends. On March 7, 1861, Adolphus married Anheuser’s daughter, Lilly, in a double wedding ceremony in which his older brother, Ulrich, married Lilly’s older sister, Anna. A little over a month after the wedding, the Civil War started and Adolphus Busch joined the Union Army. He was honorably discharged with the rank of corporal after serving out his three month enlistment.

Because of his shrewd investments, Busch profited during the war years when many of his peers suffered severe financial losses due to the wartime disturbance of the river trade. By the war’s end, Anheuser was too busy running his successful soap business to continue to give attention to his small brewery. He felt it would help to bring in someone younger and more energetic to manage the business. Having firmly established himself as a successful business manager and salesman, Busch invested in the brewery in 1865 and joined Anheuser in the brewery’s management.

Between 1863 and 1884, Adolphus and Lilly Busch had thirteen children—five boys and eight girls. Three girls died in infancy, but the remaining five, Nellie, Edmee, Anna Louise, Clara, and Wilhelmina, all married either German or German-American men and lived into late adulthood. Clara married Baron Paul von Gontard of the German empire, and became a famous trendsetter in the city of Berlin. Anna’s husband, Edward Faust, and Nellie’s husband, Edward Magnus, eventually served as vice presidents in the brewery. Of Busch’s five sons, one, Carl, was born with disabilities and required special care, while three others, Edward, Adolphus Jr., and Peter, died of appendix-related medical conditions by mid-adulthood. Only August A. Busch lived past his mid-thirties. He became second in command to Adolphus at the brewery, and eventually took over the brewery’s leadership after his father’s death.

A Good Captain

“Good men are scarce. Good captains are still scarcer.”

–Adolphus Busch

Once Adolphus Busch joined the management of the struggling Bavarian Brewery, the company’s fortunes changed immediately. Busch’s leadership and salesmanship skills, keen business sense, and good judgment in the hiring of employees helped him grow the brewery to great success in a short amount of time.

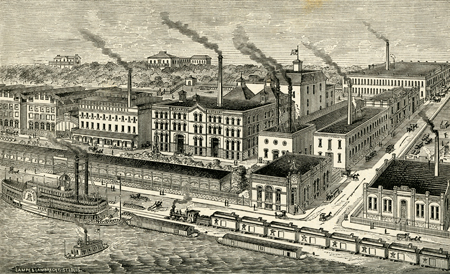

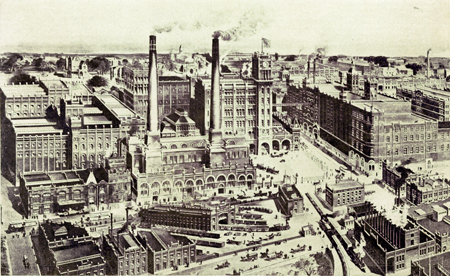

Busch not only wanted the brewery to be successful, he wanted to make it look successful as well. He set up an elegant office with expensive carpeted floors, easy chairs, and artistic decorations. This plan backfired at first because some bankers assumed he was frivolous with money and were reluctant to give him a loan to expand the brewery. Eventually, he did get the loan, and as the business expanded so did Busch’s role in the company. The company eventually became a stock-selling corporation with Busch and his wife as the major stockholders. In 1879 the corporation’s name was changed to the Anheuser-Busch Brewing Association.

The brewery’s expansion allowed it to brew and sell more beer to the country’s rapidly increasing population. The more beer that was sold, the more profits increased. Much of the profit was then used to further expand the brewery, and the cycle of sales, profit, and brewery expansion continued. In 1885 Anheuser-Busch became the leading brewery in St. Louis and by the late 1890s was the highest selling brewery in the nation.

Busch also made business decisions that improved the lives of his workers. In 1891, in response to a boycott of Anheuser-Busch beer from the American Federation of Labor, Busch became the first major brewer to sign an agreement with a labor union. This prompted other brewers to do the same. In the years after this, the average wage for American brewery workers increased and hours worked per week declined. In 1910 Busch instituted a “happiness fund” to provide entertainment for current workers, pensions for retired workers, and aid to the families of needy workers.

The King of Beers

“The Anheuser bottled beer is now found among every civilized nation, including the most fashionable cafés of the world.”

–A Tour of St. Louis; or The Inside Life of a Great City, 1878

Busch was always looking for ways to get Anheuser-Busch beer into new markets around the country. He embraced innovations in industrial technology and made frequent trips to Europe to adopt the latest brewing methods. Busch addressed the major problem of beer spoilage by investing in refrigerated railroad cars and setting up ice supply centers along railroad lines that carried his beer to markets far away from St. Louis. He also bought huge refrigeration machines to be used inside the brewery. By 1873 the Anheuser-Busch brewery found a way to use Louis Pasteur’s method of pasteurization in the bottling of beer. In this process, bottles were heated with steam and rapidly cooled off, killing the bacteria that caused spoilage. This meant that Busch could ship bottled beer anywhere in the country, even the world, without having to worry about it spoiling.

At the time, most beer was made and sold locally in the United States and many regions had their own unique tastes in beer. The Budweiser brand was created in 1876 to appeal to a wide variety of tastes, so it could be sold everywhere. It did not take long until Anheuser-Busch bottled beer was selling so well that Busch called it “the cream of our business.” Budweiser was marketed as the “King of Beers,” and went on to become the world’s best-selling brand of beer.

Busch was also involved in several other business activities. Many of his business ventures helped lower the costs of making and transporting Anheuser-Busch beer. Busch was either president, director, or a major stockholder in several companies related to brewing, marketing, or transporting beer, such as those dealing with banking, telephone communication, railroads, electric power, diesel engines, ice production and refrigeration, or bottling facilities. As profits from the Anheuser-Busch brewery steadily climbed and money from his other investments poured in, Busch became extremely wealthy.

The First Citizen and the Prince

“…there’s my friend, Prince Busch!”

–President William Howard Taft

Adolphus Busch lived a royal lifestyle. He owned mansions in Missouri, California, New York, and Germany, and built a luxury hotel named after himself in Dallas. He gave mansions as gifts to his children and paid for extravagant ceremonies at family weddings and funerals. He toured the country in a luxurious private railcar which he often loaned to family and friends at his expense. On his fiftieth wedding anniversary, a huge celebration was thrown in Pasadena where his wife was seated on a throne and given a crown worth $200,000. Another celebration was held for his brewery workers in St. Louis where an estimated 50,000 bottles of beer, 10,000 cigars, and 30,000 sandwiches were provided. Busch also had rich and powerful friends, including Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft, Edward VII of the United Kingdom, and the Emperor of Germany. Busch’s nickname among his friends was “the Prince.”

Busch was also a generous philanthropist. He funded a medical clinic at the University of Missouri and made sizeable gifts to Washington University for the study of science, medicine, and the German language, and Harvard University for a museum of Germanic culture. Busch allowed free public access to the beautiful gardens at his estate in California. A group of religious leaders named Busch the “First Citizen of St. Louis” because he donated money to so many of the city’s charities. Busch also served as a director and major promoter of the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis.

Death and Legacy

In 1906 Adolphus Busch caught a cold that turned into pneumonia. After this, he grew increasingly weaker until his death from a heart attack on October 10, 1913. His estate was worth approximately $60 million at the time of his death. Busch’s funeral was attended by thousands of mourners, including a representative from the Emperor of Germany. Reportedly, twenty-five truckloads of flowers arrived at the funeral and florists were sold out for miles around. Funeral services were held in all thirty-six cities where there were branches of the Anheuser-Busch Brewing Association and St. Louis observed a five-minute moment of silence in Busch’s honor.

The buildings built by Busch’s donations to Harvard and Washington University, both called Adolphus Busch Hall, and the Hotel Adolphus in Dallas are still in use today. The museum Busch founded at Harvard, now called the Busch-Reisinger Museum, is still the leading museum of Germanic culture in the United States. In 2007, the United States Department of Labor Hall of Fame honored Adolphus Busch for promoting fair labor practices. The Anheuser-Busch brewery stayed under the leadership of the Busch family until 2008, when it was purchased by the Brazilian-Belgian brewer InBev. The resulting corporation, Anheuser-Busch InBev, is the largest brewing association in the world.

Text and research by Todd Barnett

References and Resources

For more information about Adolphus Busch’s life and career, see the following resources:

Society Resources

The following is a selected list of books, articles, and manuscripts about Adolphus Busch in the research centers of The State Historical Society of Missouri. The Society’s call numbers follow the citations in brackets.

Articles in the Missouri Historical Review

- “This German-Born St. Louis Brewer was one of America’s Great Industrial Pioneers.” v. 52, no. 3 (April 1958), pp. 249-251.

- “Views From the Past: Missouri Landmarks.” v. 71, no. 3 (April 1977), pp. 330-332.

Articles from the Newspaper Collection

- “25 Truck Loads of Flowers Sent to Busch Funeral.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. October 25, 1913. p. 1. [Reel # 41998]

- “Adolphus Busch Dies Abroad; Wife and Son at His Bedside.” St. Louis Republic. October 11, 1913. pp. 1-3. [Reel # 45021]

- “Body of Busch to Lie in State in St. Louis.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. October 12, 1913. p. 3. [Reel # 41998]

- “Buried in Bellefontaine.” St. Louis Globe-Democrat. April 18, 1898. p. 5. [Reel # 39499]

- “Busch Employees Feast and Dance at the Coliseum.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. March 8, 1911. p. 5. [Reel # 41967]

- “Busch Services in Thirty-Six Cities.” St. Louis Globe-Democrat. October 25, 1913. pp. 1, 3. [Reel # 39657]

- “Clinic in Hospital Given by Busch.” University Missourian. October 13, 1913. p. 1. [Reel # 8823]

- “Florists are Taxed by Busch Tribute.” St. Louis Globe-Democrat. October 24, 1913. pp. 1, 4. [Reel # 39657]

- “Funeral of Adolphus Busch is Dramatic; Thousands Join in Tribute to His Memory.” St. Louis Globe-Democrat. October 26, 1913. p. 1. [Reel # 39657]

- “Gifts Worth Half Million at Busch Golden Wedding Include Kaiser’s Tribute.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. March 7, 1911. p. 1. [Reel # 41967]

- “I Will, Scharrer Says, and Squeezes Hand of His Bride.” St. Louis Globe-Democrat. March 4, 1906. p. 1. [Reel # 39573]

- “Leaves $60,000,000 Sum, Cut by Philanthropies.” St. Louis Globe-Democrat. October 11, 1913. p. 2. [Reel # 39656]

- “President and Kaiser Send Wedding Gifts to Busches.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. March 7, 1911. p. 2. [Reel # 41967]

- “Read Will to Family To-Morrow.” St. Louis Globe-Democrat. October 27, 1913. p. 1. [Reel # 39657]

- “The Remarkable True Life ‘Success Story’ of Adolphus Busch.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. October 11, 1913. p. 3. [Reel # 41998]

- “A Sadder Budweiser Firm.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. January 16, 1883. p. 1. [Reel # 41775]

- “Stories of the Personal Side of Adolphus Busch.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. October 12, 1913. p. 4.[Reel #41998]

Books and Articles

- “The First Adolphus.” Terminal Railroad Association of St. Louis Historical and Technical Society Newsletter. v. 14, no. 1-2, (Winter/Spring 2000), pp. 4-21. [REF H235.78 T2732]

- Baron, Stanley Wade. Brewed in America: A History of Beer and Ale in the United States. Boston: Litte, Brown and Company, 1962. [REF 338.47 B268]

- Brown, Mary Louise. “The Stork and Anheuser-Busch Imagery, 1913-1933.” Gateway Heritage. v. 19, no. 2 (Fall 1988), pp. 19. [REF F550 M69gh]

- Cochran, Thomas C. The Pabst Brewing Company: The History of an American Business. New York: New York University Press, 1948. [REF 338.47 C643]

- Hernon, Peter, and Terry Ganey. Under the Influence: The Unauthorized Story of the Anheuser-Busch Dynasty. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1991. [REF H235.28 An49h]

- Krebs, Roland. Making Friends is Our Business: 100 Years of Anheuser-Busch. St. Louis: Anheuser-Busch, Inc., 1953. [REF H235.35 An49]

- Plavchan, Ronald Jan. A History of Anheuser-Busch, 1852-1933. PhD Dissertation. St. Louis: St. Louis University, 1969. [REF H235.28 An49p]

- Stevens, Walter Barlow. Eleven Roads to Success Charted by St. Louisans Who Have Traveled Them. St. Louis, 1914. [REF I ST478e]

- Wilson, R. G. and T. R. Gourvish, ed. The Dynamics of the International Brewing Industry Since 1800. London, New York: Routledge, 1998. [REF HD9397.A2 D96 1998]

Manuscript Collection

- Hadley, Herbert Spencer (1872-1927), Papers, 1830-1943 (C0006)

Folders 164, 166, 167, 169, and 193 contain a series of letters by the suffragist Phoebe Couzins concerning the reclamation of a salary agreement she once had with Adolphus Busch. - Reeves, Charles Monroe (1868-1920), Papers, 1892-1970 (C3356)

Folders 10, 11, and 14 in this collection contain information about Adolphus Busch’s involvement in the Louisiana Purchase Exposition Company that promoted the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair. - State Historical Society of Missouri, Typescript Collection (C0995)

Item 88 in this collection contains “Story of the Enduring Friendship between Sen. George C. Vest and Adolphus Busch,” as told by Aleck S. Vest and Mollie Vest Jackson, the children of Senator Vest. - St. Louis Typographical Union No. 8, Records, 1856-1974 (C3661)

Folder 54 in this collection contains a formal letter of regret over Busch’s death that names Busch as an early ally to the union’s cause. - Trail, E. B. Trail (1884-1965), Collection, 1858-1965 (C2071)

Folders 44, 50, 52, 60, and 90 contain inventory sheets for beer supplies from Adolphus Busch’s shipping company. - University of Missouri, President’s Office Papers, 1892-1966 (C2582)

Folders 4297 and 4341 refer to Adolphus Busch’s donation to the University of Missouri to build a clinic for the university medical program. - Mitchell Ewing Young, Jr. (1873-1954), Papers, 1840-1949 (C1041)

Folder 615 contains an attack advertisement accusing Adolphus Busch of controlling Missouri politicians.

Outside Resources

These links will take you outside the Society’s website. The Society is not responsible for the content of the following sites:

- Adolphus Busch Hall

This website at Washington University in St. Louis gives a short history of Adolphus Busch Hall. - United States Department of Labor: Hall of Fame

A short biography of Adolphus Busch can be found at this website that recognizes Busch’s 2007 induction into the Labor Hall of Fame.