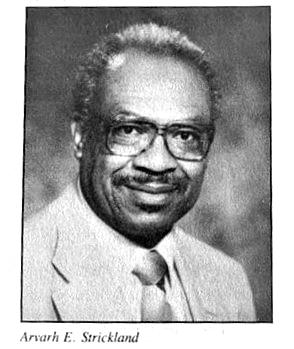

Arvarh E. Strickland

Introduction

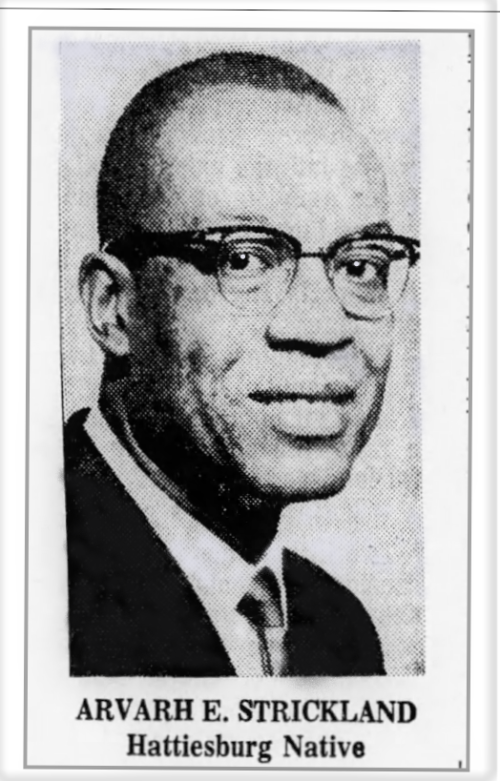

Arvarh E. Strickland was a historian, professor, and the first African American to hold a tenured position at the University of Missouri–Columbia. He wrote several well-regarded articles and books on African-American history and culture. Strickland helped to start the university’s Black Studies program and held important positions as an administrator. To his students, he was a cherished mentor committed to helping them succeed and breaking racial barriers.

Early Years

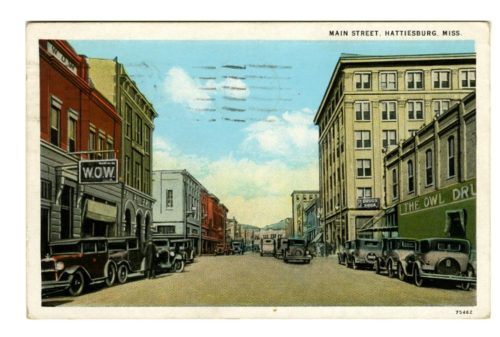

Strickland was born in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, on July 6, 1930. He was the only child of Clotiel Marshall Strickland, a teacher and cook, and Eunice Strickland, a construction worker. His parents’ relationship did not last, and he had little contact with his father before Eunice died in 1962. Arvarh was raised by his mother and grandparents close to Hattiesburg’s vibrant Mobile Street. Growing up in Mississippi, where racial segregation and discrimination were legally enforced, made Arvarh acutely aware of the injustices surrounding him.

Education

In Hattiesburg, he attended the Eureka School, the town’s only school for African American students from 1921 to 1949. He was recognized as an “outstanding student of the nation” by the General Education Board.

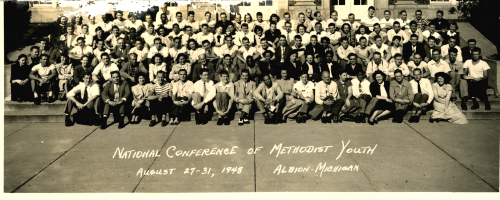

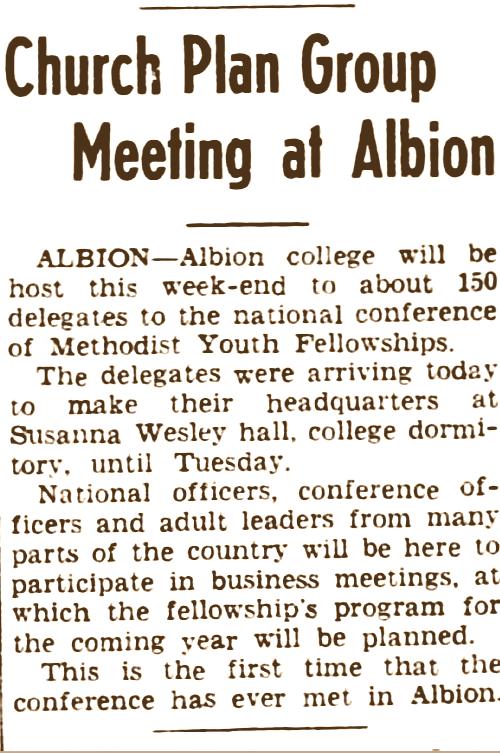

An active member of the United Methodist Church, his faith and values were an essential part of his life. In 1948, Arvarh was picked for the Mississippi Conference Methodist Youth Fellowship. As president, he led the group’s mission of helping his peers to gain a deeper understanding of their faith and connect with others in their church communities.

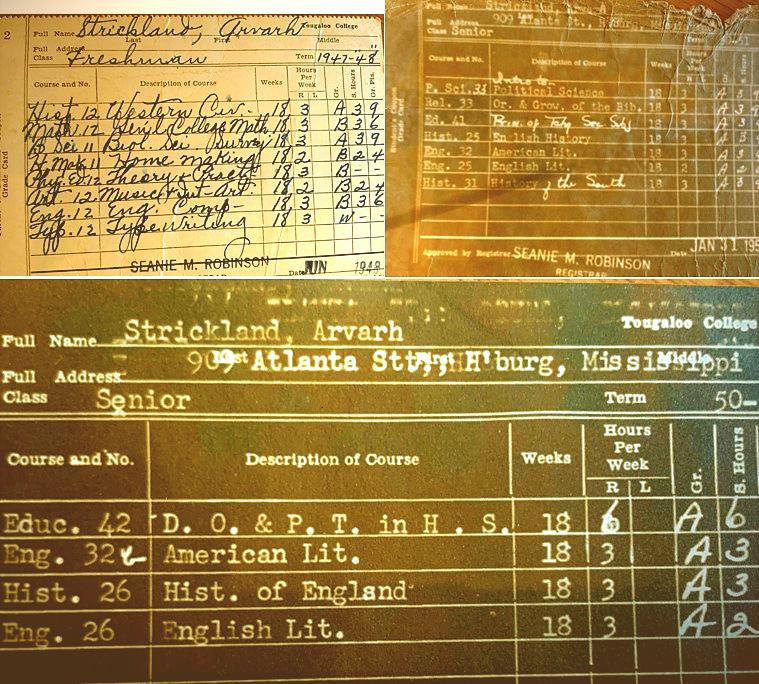

Tougaloo College & Early Career

Arvarh entered Tougaloo College, a private, historically Black school in Jackson, Mississippi, from the eleventh grade. Clotiel supported him in college by quitting her low-paying teaching job for more stable work as a cook.

While at Tougaloo, Strickland gained an appreciation for African American history, culture, and diversity. The students were all Black, but the faculty was integrated. One of Strickland’s professors was the future prolific scholar of African American history, August Meier. Faculty and students were encouraged to socialize by attending weekly chapel services and meeting for refreshments at the president’s residence on Sundays. Arvarh carried those strong values into his role as a social science teacher in his hometown, Hattiesburg. He graduated summa cum laude from Tougaloo in 1951.

the Mississippi Years

Arvarh entered graduate school at the University of Illinois–Champaign on a fellowship in education, although he wanted to pursue his passion for history. According to Strickland, his acceptance into graduate school was part of an “experiment” to see if a degree from Tougaloo “could parallel that available to black [students] in the North.” He earned his Master of Arts in 1953 and then briefly served in the US Army before returning to teaching, this time at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, the school made famous by Booker T. Washington, George Washington Carver, and other well-known Black educators. Years later, he recalled Tuskegee as “a place with a lot of tradition and a lot of elitism… I was out of the Army and somewhat anti-tradition and anti-elitist.”

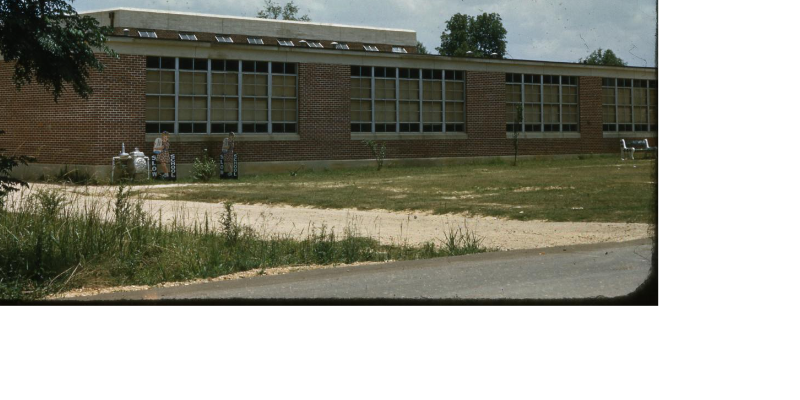

In 1956, Strickland left Tuskegee to become a high school principal in Madison County, Mississippi. After a year in Madison County, he was promoted to supervising principal. This position placed him in charge of all African American schools in the county. The job allowed him to reach one of his “greatest achievements,” requiring teachers to work toward and gain their college degrees. He believed high-caliber teachers shaped achieving students.

Strickland believed engaged students led to more involved parents, creating a perfect learning environment. In Madison County, he saw a positive change in southern Black education. After the Brown v. Board of Education ruling, the state began reluctantly supporting Black students by supplying funds for more modern school buildings and necessities like bathrooms and hot lunches. The unspoken belief among Mississippi’s white leaders was that better schools in African American neighborhoods would stall integration.

In what Strickland called his “Trojan horse” plan, he favored fundraising campaigns aimed at creating lasting changes in education in Mississippi. During his time, Strickland proudly saw “more of Madison County’s Black graduates [go] to college.”

the Universty of Illinois

But he began to think the progress he saw in Mississippi would not last. Instead of staying on, Strickland returned to the University of Illinois in 1959 as a Woodrow Wilson fellow in history. He earned his master’s degree in history in 1960 and a Ph.D. in 1962.

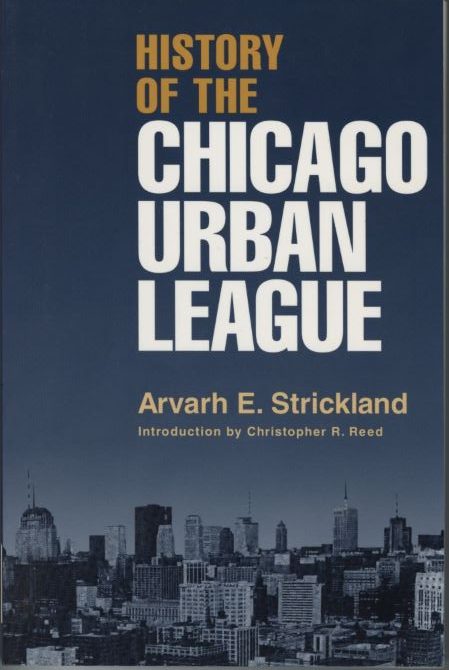

After graduate school, Professor Strickland began teaching at Chicago State University. His first book, History of the Chicago Urban League, was published in 1966. It is considered the first critical study of a Black self-help organization. Scholars credit Strickland’s work with shaping how historians view the Urban League’s impact on the African American community. Sociologist and historian Elliott Rudwick called the book “the sort of study which should be followed for other cities and other organizations.”

University of Missouri

Strickland was hired by the history department at the University of Missouri in the fall of 1969, becoming the first Black professor on the Columbia campus. With this appointment, MU began offering new undergraduate and graduate courses in African American history. As part of the university’s efforts to recruit more African American students, Strickland oversaw course changes and introduced Afro-Americans in the Twentieth Century to the available list of courses. The class is still offered in the history department.

The same year he broke barriers as the first Black faculty member hired by MU, Strickland and his family became the first Black members of the Missouri United Methodist Church in Columbia. Strickland remained active in the church for decades, holding several church committee and council appointments.

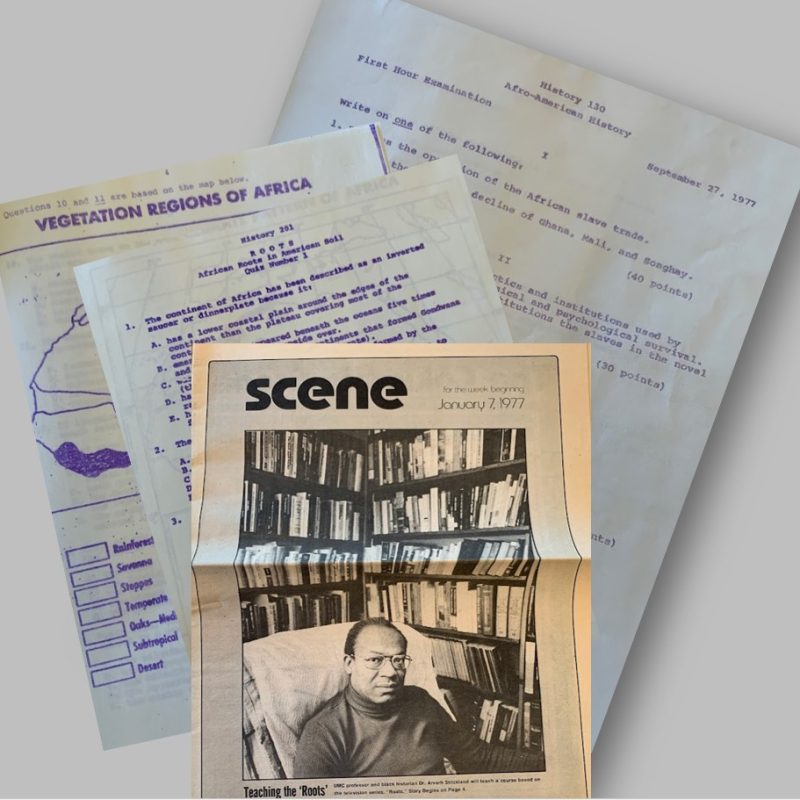

In 1977, he taught a class using the ABC television network premiere of Roots, a miniseries watched by millions of viewers that exposed many of them to Black history for the first time. The course, African Roots in American Soil, was designed by Miami Dade College in Florida and based on the book Roots: The Saga of an American Family by Alex Haley. It was designed to explore African American history, culture, and identity.

The African Roots in American Soil class was an example of Professor Strickland’s commitment to bringing exciting yet challenging learning opportunities to MU. As a member of the Guardians, Inc., and the Kiwanis Club, both service charities aimed at helping children, Strickland’s commitment to young people in Columbia extended beyond the university. His passion for history and culture made him a valued trustee of the State Historical Society of Missouri, a position he held from 1974 until his death. Strickland received the Society’s Distinguished Service Award in 1997 for his decades of service to the history profession and the state of Missouri.

Legacy

In 2007, the General Classroom Building on the MU campus was renamed Arvarh E. Strickland Hall. During the dedication, a crowd of “more than 100 former students, colleagues, friends and well-wishers” came to celebrate. When asked to speak, Strickland told the crowd, “This is not about me. This is a tribute to Lloyd Gaines, to Lucile Bluford, to all of those folks who came, and to some who had tried and had the door shut in their face, and others who got into this institution.”

Arvarh E. Strickland died in Columbia. Missouri, on April 30, 2013. He was 82 years old. Dr. Strickland’s students valued him as a stern but compassionate educator. He held students to the same high standards that he had for himself. He encouraged and supported his students long after graduation and continued advocating for them in their professional careers.

Text and research by Bridget D. Haney

References and Resources

For more information about Arvarh Strickland’s life and career, see the following resources:

Society Resources

The following is a selected list of books, articles, and manuscripts about Arvarh Strickland in the research centers of The State Historical Society of Missouri. The Society’s call numbers follow the citations in brackets.

Articles from the Newspaper Collection

- “Minority Recruiter At Missouri U.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. December 18, 1971. p.3.

- “M.U. Plans to Offer Negro History Class.” Springfield News-Leader. August 1, 1969. p. 10.

- Scher Zagier, Alan “M.U. honors historian, first black professor.” Springfield News-Leader. October 20, 1953. p. 2.

- “‘Soul Week’ Activities Continuing.” Sedalia Democrat. March 22, 1971. p. 3.

Arvarh E. Strickland Papers, (CA4995)

Personal and professional papers of historian, educator, and University of Missouri administrator.

In 1971, several prominent black citizens of Columbia, Missouri, established The Guardians, Inc., a men’s club founded to “provide social activities and personal uplift” for its members and to serve as a leadership force within the black community.

Kiwanis Club of Columbia, (CA6035)

Records of a Columbia, Missouri, service organization include annual reports, minutes, correspondence, and financial records.

- “Dr. Arvarh E. Strickland.” Missouri Times Vol. 9, no. 1 (May 2013): 2.[F550 M691n]

- Strickland, Arvarh E. 2012. History of the Chicago Urban League. Columbia: University of Missouri Press. [362.84 St85 2001]

Outside Resources

Archives

Mississippi Department of Archives & History

MDAH collects and preserves objects of all types that help us tell the great story of Mississippi. Holdings include archival records, historic objects, and archaeological artifacts that span 15,000 years of Mississippi history.

University Archives, University of Missouri

University Archives is the depository of official records of the University of Missouri as well as of the administrative records of the University of Missouri System.

Articles

“The University of Missouri-Columbia is Proud to Announce The Arvarh E. Strickland Distinguished Professorship in African-American History and Culture.” The Journal of Negro History 83, no. 1. (Winter 1998): 100-105.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/2668562

Rudwick, Elliott. Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1908-1984) 60, no. 1 (1967): 82-83.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/40190251

Newspapers

Battle Creek Enquirer, Battle Creek, MI.

Hattiesburg American, Hattiesburg, MS.