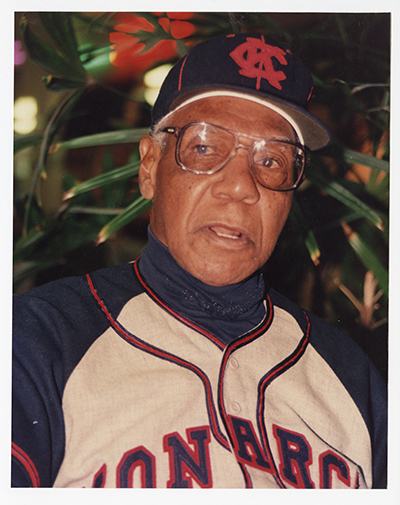

Buck O’Neil

Introduction

Buck O’Neil was a famous baseball player, manager, coach, and scout who was instrumental in bringing national attention and recognition to the Negro Leagues. He helped other Negro Leaguers such as his Kansas City teammate Satchel Paige get inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame, and years after his death he was finally elected to the Hall of Fame himself. He also helped create and run the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City.

Early Years and Education

John Jordan “Buck” O’Neil Jr. was born on November 13, 1911, in Carrabelle, Florida, a small fishing village on the Gulf coast south of Tallahassee. His father, John Jordan O’Neil Sr., was from southern Georgia and his mother, Luella O’Neil, was from Quincy, Florida. Buck had an older sister named Fanny and a younger brother named Warren. His grandfather, Julius O’Neil, was taken on a slave ship from West Africa to the United States when he was a young boy and forced to work on a plantation in the Carolinas. After being freed, Julius moved to southern Georgia, near the Florida border, where John Jordan O’Neil Sr. grew up.

When Buck was a child, his father played on a local baseball team as a first baseman. Buck sometimes traveled with his dad to Florida towns where the team played. He liked baseball so much that he wanted to start playing too. When he was eight years old, his family moved to Sarasota, Florida, where his mother got a job cooking for the members of the Ringling Brothers Circus. Sarasota was a hotspot for baseball, as many major-league teams held spring training in town or nearby. He and the other kids in Sarasota loved seeing white stars like the New York Yankees’ Babe Ruth each spring. They also kept up with African American baseball teams by reading black newspapers. During Buck’s childhood, both baseball and newspapers were segregated by race.

As a teenager, Buck worked as a box boy for a company that harvested celery. His job was to put empty crates in rows for other workers to pack. Most box boys could only carry two boxes, but Buck was strong and could carry four. He did this work for three growing seasons and made $1.25 a day.

In the 1920s, Florida’s schools were segregated, and there were only four high schools for black children in the entire state. When it was time for him to start high school in 1926, Buck’s grandmother told him that he would not be able to attend Sarasota High School because it was only for white students. He cried, but his grandmother told him not to worry because one day all kids would be able to go to Sarasota High School. Buck eventually was able to attend Edward Waters College, a small Methodist school in Jacksonville that provided high school classes for black teenagers from Florida.

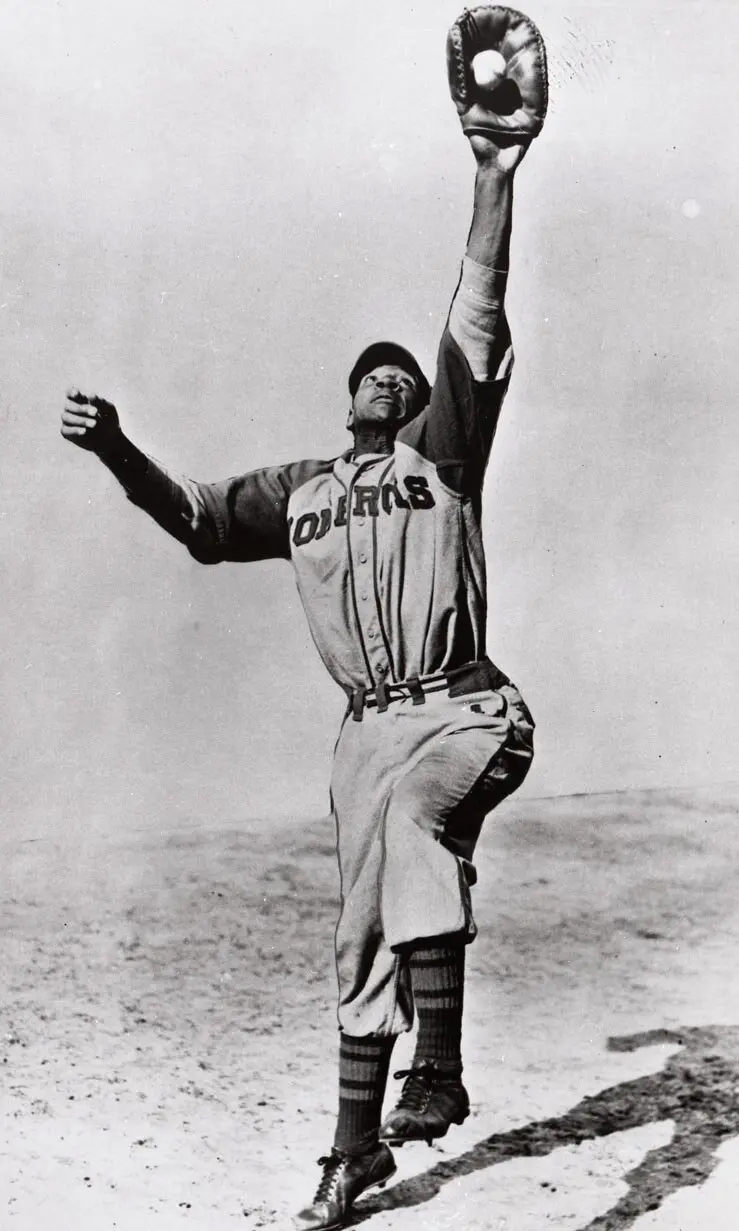

By then, Buck had already started his baseball career. At age twelve he played for a semipro team, the Sarasota Tigers, when they asked him to fill in for their first baseman, who was ill. Buck played for them for two seasons. He also played baseball at Edward Waters College, where his coach, Ox Clemons, played an important role in teaching him the sport.

“Watching [Ox], I learned how to be tough, how to fight and survive, but also how to handle people. I had always been able to get along with people, but Ox showed me that everybody has a different personality and you can’t treat all people the same way. Some you’ve got to stroke, some you’ve got to challenge to get the best out of them. But the most important rule was that every player on a team was equal.” – Buck O’Neil

Early Baseball Career

Around 1933, O’Neil joined his first fully professional team, the Tampa Black Smokers. He played with them for just a short time before receiving an offer to join the Miami Giants. At the time, “Giants” had become a commonly used name for a black team. Many white newspapers refused to print pictures of African Americans, but the name “Giants” told newspaper readers that the players were Black.

Buck then joined the New York Tigers, a team that made its living by “barnstorming,” or traveling across the country to play many exhibition games. When he came home from the team’s travels six months later, he told his mother he would never go away again. He changed his mind a few months later, however, when he was asked to play for the Shreveport Acme Giants in the spring of 1936.

At the end of his first season with the Acme Giants, he and some of his teammates joined players from a Texas team called the Black Spiders to form an all-star squad to play in Mexico. Mexico offered them a spot in its professional league if they could win a game against a Mexican team. But they lost the game and left the country.

“[The Acme Giants] played in some pretty small farm towns in the Dakotas, Montana, Iowa, and Canada, but even though there weren’t any black towns up there, we had no problems getting served in restaurants and hotels. And this goes along with something I’ve always thought, that wherever I went where there weren’t many blacks, things were easier for us than where there were a lot. You’d think it might be just the opposite, but it was some kind of compensation or something. When there were just a few or no blacks in a town, we were treated better than we were in places like Kansas City or Omaha, because people hadn’t formed any opinions, positive or negative, about us. They didn’t have all these Jim Crow rules because the issue hardly ever came up.” – Buck O’Neil

The Big Leagues

In 1937, Buck signed with the Memphis Red Sox, a team in the Negro American League, one of the top leagues for black players. Halfway through the season he left to play for the Zulu Cannibal Giants. (“Jumping” teams in midseason to earn more money was a common practice.) While barnstorming for the Giants, O’Neil received his nickname “Buck” after a case of mistaken identity when the team’s promoter, Syd Pollock, confused him with the owner of one of his former teams, the Miami Giants. The Miami owner’s name was Buck O’Neal. The new name stuck.

Buck jumped back to the Memphis Red Sox for the last month of the 1937 season. In 1938 he began playing for another Negro American League team, the Kansas City Monarchs. He remained with the Monarchs as a player or manager from 1938 until 1955, except for two seasons that he missed while serving in the US Navy during World War II.

On Easter Sunday in 1943, Buck had what he considered to be the greatest day of his life. On that day, he played first base for the Kansas City Monarchs against the Memphis Red Sox. In his first at bat, he hit a double. After hitting a single his next time up, he hit the ball over the fence for a home run in his third at bat. On his fourth trip to the plate, he hit the ball hard enough for an inside-the-park home run, but he stopped running at third. With the triple, he had hit for the cycle: single, double, triple, and home run. But his great day was not over. That night at the players’ hotel, a friend introduced him to some local schoolteachers, including his future wife, Ora Lee Owens. His first words to her were, “My name is Buck O’Neil, what’s yours?”

Buck went into the navy not long after meeting Ora. He served in the Pacific, where he loaded and unloaded ships in the Mariana Islands and at Subic Bay in the Philippines. Buck and Ora married in 1946 after his return from military service, and he went back to playing for the Monarchs. He was the team’s first baseman until 1951. In 1948 he also became the team’s manager, staying in that position through 1955 and leading the team to two league pennants.

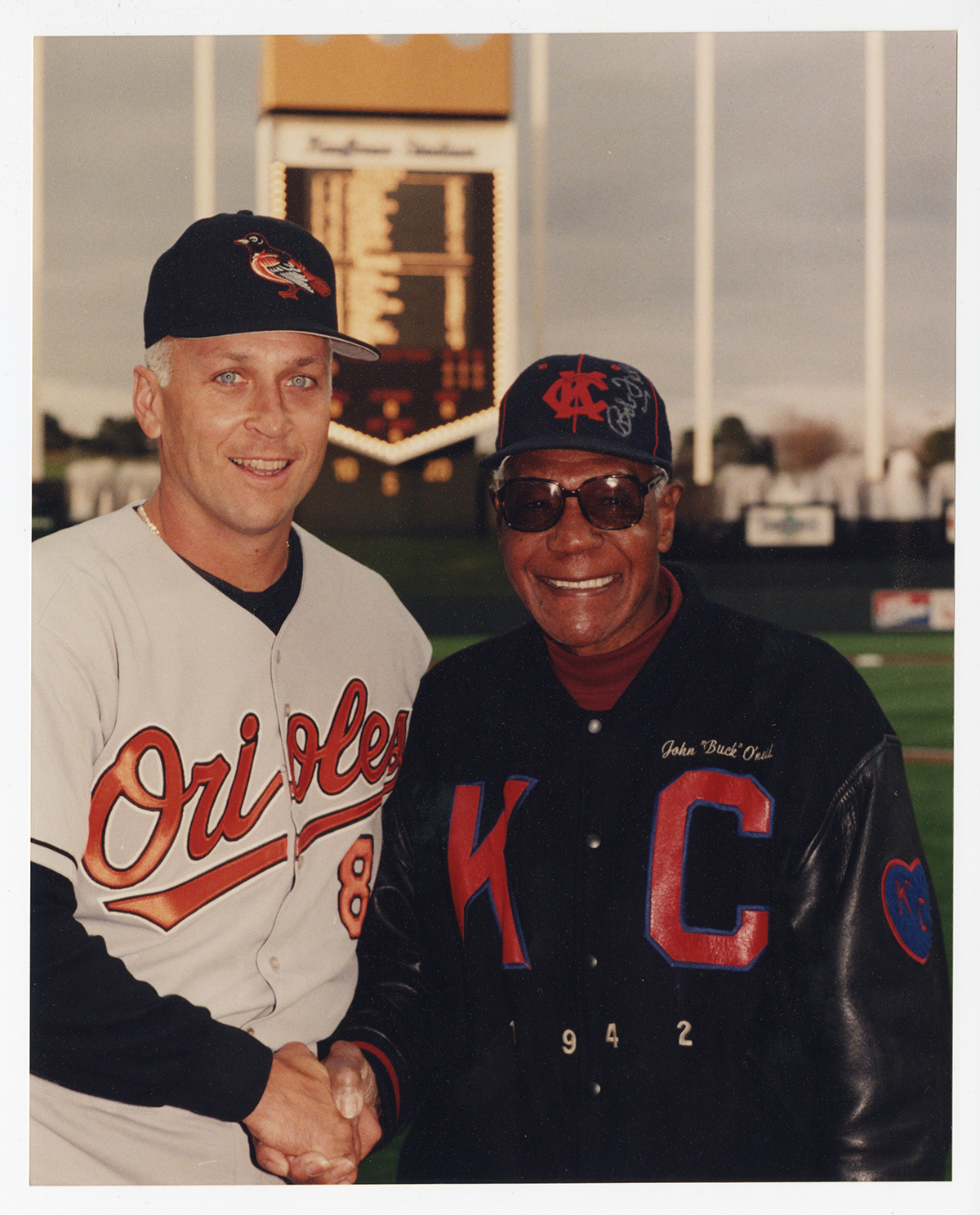

After 1955, O’Neil left the Negro Leagues to work for the Chicago Cubs as a scout. In June 1962 he was named a coach for the Cubs, becoming the first African American to coach for a Major League team. He went back to scouting in 1964 and continued in that role until he retired in 1988. Almost immediately after retiring from the Cubs, however, he received a call from Kansas City Royals’ general manager John Schuerholz, who offered him a job as a special assignment scout.

“Working for Kansas City meant considerably less travel … and that I could watch games from those great scout seats behind home plate, which was even better. Watching baseball games had become so much a part of the rhythm of my life that I had begun to wonder what I was going to do with those free evenings.” – Buck O’Neil

Recognition for Negro Leagues

After Jackie Robinson ended racial segregation in baseball in 1947, the Negro Leagues gradually faded away as its star players began leaving to play in the Major Leagues. In later years, O’Neil always wanted the Negro League players to receive the same recognition and respect as white ballplayers. His cause got a big boost when he was featured in Ken Burns’s 1994 award-winning documentary series, Baseball. Many who saw the documentary fell in love with Buck, who at age eighty-two still had a bright outlook on life, was a great storyteller, and had a sweet, friendly personality. Baseball gave O’Neil a chance to talk to a large national audience about the sport and the players he had devoted his life to.

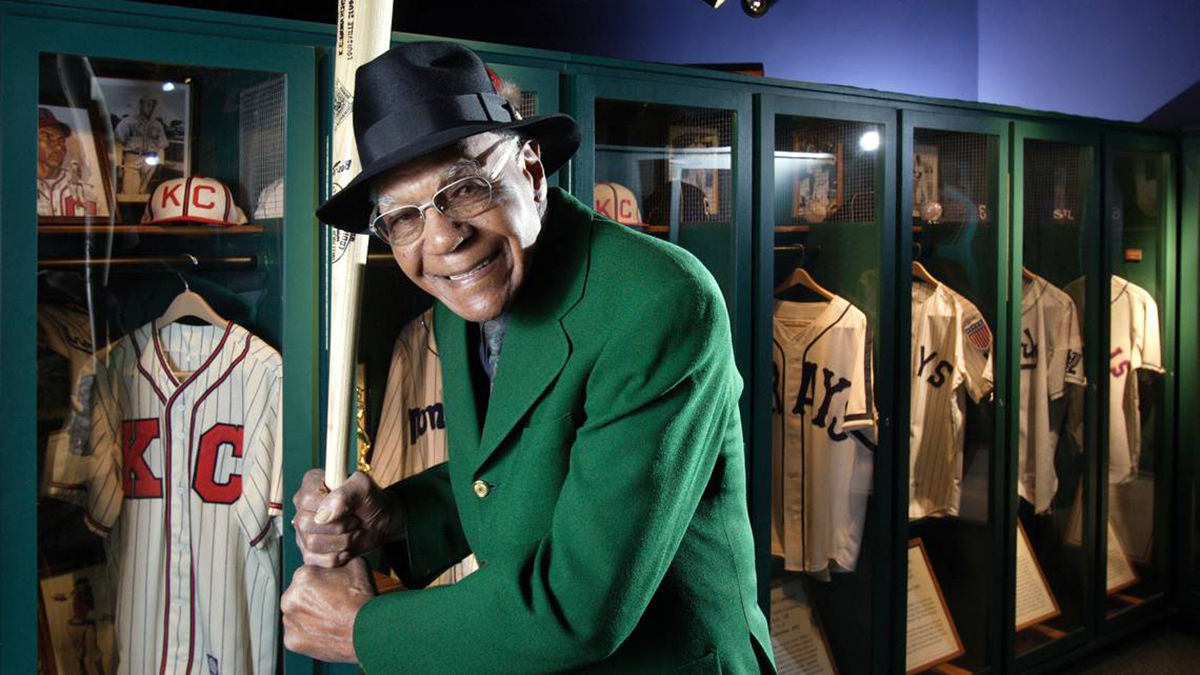

After the documentary aired, O’Neil began making 200 appearances a year in big cities and small towns alike, promoting the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City that he had helped create in 1991. He traveled to all corners of the United States to get people to recognize the greatness of the Negro Leagues and its players.

“The newfound popularity of the Negro leagues has come a little too late to save the Monarchs, but it’s gratifying nonetheless. It’s wonderful that folks are remembering the people who built the bridge across the chasm of prejudice, not just the men who later crossed it.” – Buck O’Neil

Negro Leagues Players in the Baseball Hall of Fame

O’Neil worked tirelessly to get Negro Leagues players inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. The first to be inducted was his friend Satchel Paige in 1971. Josh Gibson followed the next year, and seven more of the Negro Leagues’ biggest stars were inducted in the 1970s. Two players were inducted in the 1980s, five in the 1990s, and two in the early 2000s. Another seventeen players and team owners were added in 2006 when the Hall of Fame created a committee of twelve scholars to select more Negro Leaguers who had been overlooked.

The committee made a ballot of thirty-nine players, including Buck O’Neil. But he was not among those chosen, to the outrage of his many fans from the Baseball documentary. Some of his supporters were angry as well when the Hall of Fame invited O’Neil to speak at the induction ceremony after he had been snubbed. However, Buck showed he was more pleased that seventeen Negro Leagues members had received baseball’s greatest honor than he was upset about not being among them.

Death and Legacy

Buck O’Neil passed away on October 6, 2006, in Kansas City after a long illness. He was about a month shy of his ninety-fifth birthday. People from all over the country paid tribute to him. George W. Bush honored him with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest honor a civilian can receive, on December 7, 2006. According to a White House press release, O’Neil was chosen because of his “excellence and determination on and off the baseball field.” O’Neil’s younger brother Warren accepted the award, one that only thirteen baseball players have ever received, on his brother’s behalf.

In 2007, O’Neil received a lifetime achievement award from the National Baseball Hall of Fame—the award now bears his name. In 2008, a life-size statue of O’Neil was placed in the Hall of Fame. In 2016, Kansas City’s Broadway Bridge was renamed the Buck O’Neil Bridge. And at Kauffman Stadium, where the Kansas City Royals play, there is the Buck O’Neil Legacy Seat to honor those who embody O’Neil’s spirit and love for Kansas City. This red seat, the only one in the stadium, is located where O’Neil sat when he scouted for the Royals.

On December 5, 2021, Buck O’Neil was elected to the 2022 class of the National Baseball Hall of Fame by the Early Baseball Era Committee.

“You got to give people love. I can honestly say that I love everybody and I hate no one. I hate cancer, which has touched so many of our lives, and I hate AIDS, and I hate hatred–men remain in ignorance so long as they hate. But I hate no human being.” – Buck O’Neil

Text and research by Avery Renshaw with research assistance by Aleksandra Kinlen

References and Resources

For more information about Buck O’Neil’s life and career, see the following resources:

Society Resources

The following is a selected list of books, articles, and manuscripts about Buck O’Neil in the research centers of The State Historical Society of Missouri. The Society’s call numbers follow the citations in brackets.

Articles from the Newspaper Collection

- “A Ball Club Sale.” Kansas City Star. February 12, 1948. p. 20. [Reel # 20723]

- “Buck O’Neil: I Was ‘On Time.’” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. June 22, 1996. p. 23. [Reel # 44250]

- “Cubs Sign 1st Negro Coach in Majors.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. May 29, 1962. p. 16. [Reel # 43142]

- Etkin, Jack. “O’Neil Provided Williams a Steady Hand.” Kansas City Star. January 15, 1987. p. 23. [Reel # 22470]

- “Former Blues, Monarchs, A’s Plan Goodbye.” Springfield Leader and Press. September 22, 1971. p. 33. [Reel # 49321]

- Frederick, Thomas. “KC Connection began Baseball’s Globalization.” Kansas City Star. October 26, 2004. p. 23. [Reel # 23501]

- “In Negro Loop Opener.” Kansas City Star. May 7, 1950. p. 29. [Reel # 20776]

- “In Negro Opener Here.” Kansas City Star. April 27, 1947. p. 28. [Reel # 20713]

- “The List of Inductees This Summer.” Daily Journal (Flat River, Mo.). June 3, 1994. p. 6. [Reel # 33461]

- “KC ‘Monarchs’ to Play Elmer.” Macon Chronicle-Herald. June 25, 1946. p. 6. [Reel # 27356]

- Kerkhoff, Blair. “Negro Leagues Museum in Kansas City Will Be in Spotlight for Celebration.” Kansas City Star. August 16, 2020.

- “Monarchs Lose a Pair.” Kansas City Times. August 4, 1947. p. 11. [Reel # 24104]

- Neal, La Velle E., III. “Negro Leagues Mark Anniversary.” Kansas City Star. February 13, 1995. p. 20. [Reel # 22905]

- Posnanski, Joe. “Buck’s Lessons in Joy Live On.” Kansas City Star. November 13, 2011. p. A1. [Reel # 55132]

- “Royals to Bring Old Timers Back.” Kansas City Times. September 22, 1971. p. 24. [Reel # 21736]

- Skretta, Dave. “Friends, Strangers Mourn Death of Baseball’s O’Neil.” Springfield News-Leader. October 8, 2006. p. 2. [Reel # 50242]

- “The Sports Roundup.” Kansas City Star. August 29, 1943. p. 18. [Reel # 20680]

- “A Strong Monarch Foe.” Kansas City Times. June 30, 1941. p. 13. [Reel # 24074]

- Thompson, Wright. “Now All O’Neil Can Do Is Wait.” Kansas City Star. February 26, 2006. p. 16. [Reel # 23579]

Books and Articles

- O’Neil, Buck, Steve Wulf, and David Conrads. I Was Right on Time. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996. [REF F508.1 On199]

- Plum, Stacy, Kansas City Missouri School District, and Primitivo Garcia Elementary School (Kansas City, Mo.). Give It Up!: The Story of John “Buck” O’Neil. Kansas City, MO: Local Investment Commission, 2006. [REF IJ On22]

- Spivey, Donald. “If You Were Only White”: The Life of Leroy “Satchel” Paige. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2012. [REF F508.1 P152sp]

Manuscript Collection

- Kansas City Monarchs Oral History Collection, 1978-1981 (K0047)

This collection contains oral history interviews and correspondence with eighteen individuals who played with or were associated with the Kansas City Monarchs.

Outside Resources

These links will take you outside the Society’s website. The Society is not responsible for the content of the following websites:

- Chronicling America

This website is hosted by the Library of Congress and provides access to historic newspapers, including out-of-state publications that mention O’Neil’s early accomplishments in baseball from the 1930s to the 1960s. - MOspace Institutional Repository

This website is an online repository for creative and scholarly works and other resources created by faculty, students, and staff at the University of Missouri. The open access site includes a thesis on the history of the Negro Leagues by Daniel Isaac Stroud From Dachau to the Dugout: Black America’s Diamond-Lined Response to Racism (2011). - National Baseball Hall of Fame

This website provides biographical information about O’Neil as well as statistics and several interviews and speeches. O’Neil was finally inducted into the organization in 2022. - Negro Leagues Baseball Museum

The website of a privately funded museum, founded in 1990 in part through the efforts of O’Neil, dedicated to preserving the history of Negro League baseball in America. - Society for American Baseball Research

This website provides information to foster the research and dissemination of the history and record of baseball primarily through the use of statistics, containing a biography of O’Neil as well as a speech and an oral history interview with the famous ball player.