Carry A. Nation

Introduction

Carry Nation was a famous leader and activist before women could vote in America. She believed that drunkenness was the cause of many problems in society. Nation fought with fierce and witty words to make her case that people should not drink alcohol or use tobacco. She gained national attention when she started using violence. Though she was beaten and jailed many times for “smashing” saloons, Carry Nation remained opposed to drinking and smoking throughout her life. Her crusade against drinking contributed to the passing of the Eighteenth Amendment.

Early Years

Carrie Amelia Moore was born on November 25, 1846, in Garrard County, Kentucky. Her parents were George Moore and Mary Campbell Moore. Her father wanted to spell her name “Carry,” but as a child she was “Carrie.” The Moore family lived on a large farm where Carrie grew up with several siblings and spent many hours with the people the family enslaved. All her life she was comfortable with people of various races.

In 1854, with civil war on the horizon, Carrie’s father moved the family to High Grove Farm near Belton in Cass County, Missouri. Rather than finding peace, Carrie’s family found people divided over political issues. In 1862 the Moores moved again, this time to Texas.

The next year, the family returned to their farm in Missouri, but the Civil War followed them. Union commanders ordered everyone out of parts of the Kansas-Missouri border, including Cass County. The Moores moved to Kansas City, and Carrie learned the brutal side of battle when she traveled with another woman to nurse soldiers after a raid in Independence, Missouri.

A Difficult Start

After the war, the Moores returned to their farm. Carrie, now twenty-one, married Charles Gloyd on November 21, 1867. Gloyd, once a boarder at the Moore’s house, was a young physician who had fought for the Union. Carrie did not realize that Gloyd, whom she loved dearly, had a severe drinking problem. Soon Carrie became pregnant, and it was clear that Gloyd could not support her because of his excessive drinking. Heartbroken, Carrie returned to her family home. When her only child was born on September 27, 1868, Carrie named her Charlien after her husband. Only six months later, Charles Gloyd died.

Carrie sold land her father had given her as well as her husband’s books and medical equipment and built a small house in Holden, Missouri. There she lived with her child and mother–in–law. From May 1871 to July 1872 Carrie Gloyd attended school to earn a teaching certificate at the Normal Institute in Warrensburg, Missouri. She taught in Holden for four years.

A New Life

In 1874 Carrie Gloyd married David Nation, a widower with children who was nineteen years older than she. David Nation was a journalist for a Warrensburg newspaper. He was also a lawyer and preacher. Together, they lived with their children in Warrensburg for a few years. Then they moved to Texas in 1877. While her husband practiced law, Carrie Nation managed a hotel in Columbia and then bought and ran one in Richmond, Texas, for ten years. She was a deeply religious person and started having visions and dreams during this period.

Mother Nation

In 1889 Nation’s husband became a preacher, and they moved to Medicine Lodge, Kansas. Here she began a career of charity and religious work and became known as “Mother Nation.” She took a deep interest in helping unfortunate people, especially women and children, and became known for her generosity. Nation organized a chapter of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU). The WCTU had helped pass a Kansas law against selling alcohol. In Missouri, each county could decide to be wet or dry.

Nation also tried to help prisoners in the jail. She came to believe that alcohol had caused the troubles of the inmates. Illegal bars and men’s clubs in Kansas still served liquor. Nation and another member of the WCTU decided to get rid of the bars by standing outside them, praying loudly and singing hymns. Soon, the bars in Medicine Lodge were closed.

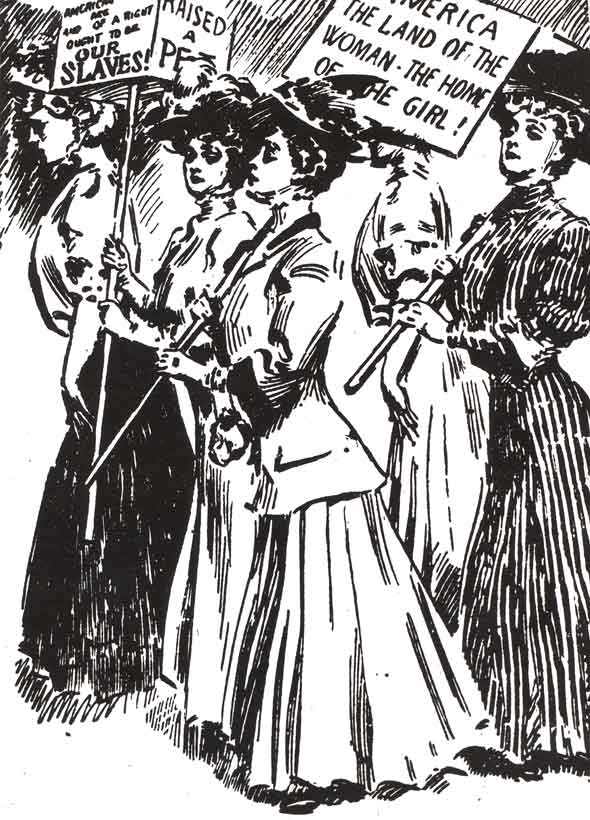

In 1900 Nation believed that God told her to go to Kiowa, Kansas, and close the bars there. Rather than use hymns and prayer, however, Nation threw bricks. She continued her destructive tactics in Wichita, Kansas. In Topeka in 1901, someone handed her a hatchet.

Nation was a strong, six-foot-tall woman, and when her method became violent, people noticed. The Kansas WCTU presented her with a gold medallion inscribed, “To the Bravest Woman in Kansas.” The crowds of followers grew, but her marriage fell apart. By November 1901, she was divorced. Again alone, Nation sold little pewter hatchets to raise money and took on speaking engagements. She was beaten and jailed many times. After one “smashing,” Nick Chiles, a black politician and bar owner, bailed her out of jail. He also published her first newspaper, The Smasher’s Mail.

The Hatchet was Nation’s second attempt at starting a regular magazine. It contained her writings, news from saloon fighters, and letters from supporters throughout the United States. Besides writing about the evils of liquor, Nation wrote articles suggesting that women should get the vote, articles that gave advice about rearing children, and articles about the joys of a happy home.

Final Years of Fury

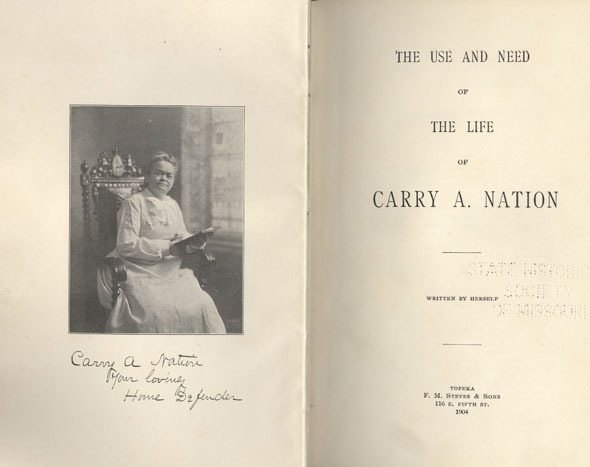

In 1903 Carrie Nation officially changed her name to “Carry,” saying it meant “Carry A Nation for Prohibition.” When her autobiography was published, she made enough money to buy a house in Kansas City, Kansas, to shelter the wives and mothers of drunkards. Later, a lecture tour took her to Great Britain.

Many people made fun of Carry Nation. A group of college students lured her to campus by pretending to support her, and used her visit to put her down. Instead of becoming angry, she suggested that women should have the power to change things through the democratic process of voting: “The loving moral influence of mothers must be put in the ballot box.”

Exhausted and ill, Carry Nation retired to Eureka Springs, Arkansas, and bought a house large enough for her and several women who had lost their homes because of alcoholic husbands. She collapsed while giving a lecture in Eureka Springs in January 1911 and died on June 2, 1911, at the age of 64. She is buried beside her mother in Belton, Missouri.

Carry Nation’s Legacy

Carry Nation’s work paved the way for two amendments to the United States Constitution. The Eighteenth Amendment, passed in 1919, prohibited the sale of alcohol, and the Nineteenth Amendment, ratified in 1920, allowed women to vote. In 1933 Prohibition ended with another constitutional amendment.

Text and research by Margot Ford McMillen and Carlynn Trout

References and Resources

For more information about Carry A. Nation’s life and career, see the following resources:

Society Resources

The following is a selected list of books, articles, and manuscripts about Carry A. Nation in the research centers of The State Historical Society of Missouri. The Society’s call numbers follow the citations in brackets.

Articles from the Missouri Historical Review

- Caldwell, Dorothy. “Carry Nation, A Missouri Woman, Won Fame in Kansas.” v. 63, no. 4 (July 1969), pp. 461-488.

- “Temperance Societies Flourished in Missouri a Century Ago.” v. 46, no. 2 (January 1952), pp. 147-149.

Articles from the Newspaper Collection

- Braniff, E. A.“Carry Nation Recalled as a Crusader Who Could Laugh at Own Discomfiture.” Kansas City Times. March 29, 1948. [Reel # 24108]

- “Mrs. Nation Fired in Police Court: Judge McAuley Assesses the Joint-Smasher $500 and Orders Her out of Town.” Kansas City World. April 15, 1901. [Reel # 24250]

- “The Nation Funeral Here.” Kansas City Star. June 10, 1911. [Reel # 23906]

- “Topeka’s Sunday Smashers.” Kansas City Star. February 18, 1901. [Reel # 23870]

Books and Articles

- Asbury, Herbert. Carry Nation. New York: A. A. Knopf, 1929. [REF F508.1 N213a]

- Christensen, Lawrence O., William E. Foley, Gary R. Kremer, and Kenneth H. Winn, eds. Dictionary of Missouri Biography. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1999. pp. 428-431. [REF F508 D561]

- Day, Robert. “Carry from Kansas Became a Nation All unto Herself.”Smithsonian, v. 20 (April 1989), pp. 147-164. [REF Vertical File]

- Grace, Fran. Carry A. Nation: Retelling the Life. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001. [REF F508.1 N213gr]

- Madison, Arnold. Carry Nation. Nashville: T. Nelson, 1977. [REF F508.1 N213m]

- Marlow, Lydia. “Carry Nation.” Show Me Missouri Women: Selected Biographies. Kirksville, MO: Thomas Jefferson University Press, 1989, vol. 1, pp. 236-237. [REF F508 Sh82]

- May, Leland. “The Saloon Smasher.” Rural Missouri, April 1983, pp. 4-5. [REF Vertical File]

- Nation, Carry Amelia. The Use and Need of the Life of Carry A. Nation, Written by Herself. Topeka: F. M. Steves & Sons, 1905, 1908. [REF F508.1 N213]

- Taylor, Robert Lewis. Vessel of Wrath: The Life and Times of Carry Nation. New York: New American Library, 1966. [REF F508.1 N213t]

- Waal, Carla, and Barbara Oliver Korner, eds. Hardship and Hope: Missouri Women Writing about Their Lives, 1820-1920. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1997. pp. 184-192. [REF F508 W111]

Manuscript Collection

- The Missouri Collection (C3982)

A collection combining miscellaneous small acquisitions related to Missouri places, individuals, organizations, and events. Includes a folder on the Missouri Anti-Saloon League. - Lucile Morris Upton Papers (C3869)

The personal and professional papers of a Springfield, Missouri, journalist and writer are especially strong in the history of Springfield and the Ozarks region and in Ozark folklore. Information about Carry Nation is included in several files, including a photograph of her giving a speech in Excelsior Springs. - Women’s Christian Temperance Union (Columbia, Mo.) Minute Book (C0262)

Nation is mentioned in the book, which contains the constitution, meeting minutes, roll of members, activities, and bylaws of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union.

Outside Resources

These links, which open in another window, will take you outside the Society’s website. The Society is not responsible for the content of the following websites:

- Nation, Carry A. The Use and Need of the Life of Carry A. Nation

This website provides the entire autobiography of Carry Nation, published in 1905. - Kansas State Historical Society

This website provides a biography of Carry Nation, images pertaining to her life in Kansas, and images of several of her personal belongings. The Kansas State Historical Society also holds a collection of her papers. - The Portal to Texas History

This website has many pictures from Carry Nation’s life in Texas and other people and places as well. - Waymarking

This website provides a photograph of Carry Nation’s grave. It can also help you find interesting places, including the gravesites of other Historic Missourians, all over the world.