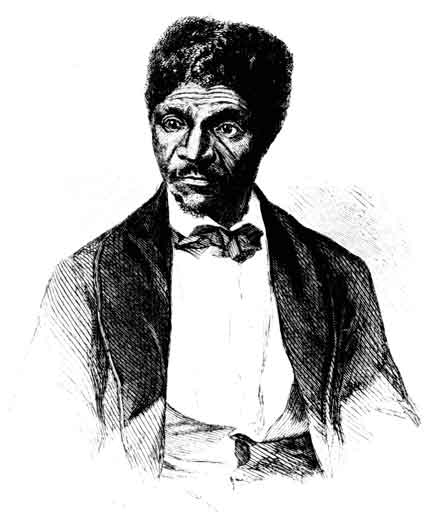

Dred Scott

Introduction

Dred Scott was a man born into slavery who tried many times, but failed, to gain his freedom through the Missouri courts. When his case reached the U.S. Supreme Court, the differences between proslavery and antislavery opinions in the United States were very clear. The controversial outcome of Dred Scott’s court case eventually contributed to the outbreak of civil war between the southern and northern states.

Early Years

Dred Scott was born into slavery in Virginia around 1800. He was enslaved by Peter Blow and his wife, Elizabeth Taylor Blow, both Virginians. Dred grew up, probably in slave quarters, on the Blow property in Southampton County. In 1818, when Dred Scott was a young man, he moved with the Blows, their six children, and several other enslaved people to a cotton plantation in Alabama. For the next twelve years, Scott worked for the Blows. Two more children, sons Taylor and William, were born to the Blows in Alabama.

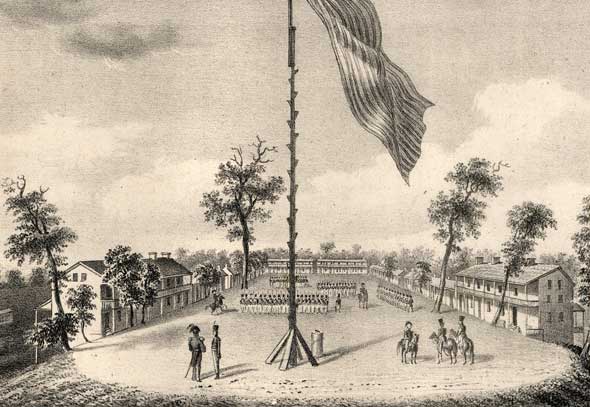

In 1830, Scott moved again when the Blow family gave up farming and relocated to St. Louis, Missouri. Here they ran a boardinghouse called the Jefferson Hotel. Elizabeth Blow died in 1831 with Peter following in 1832. Before he died, however, Peter Blow sold Dred Scott to Dr. John Emerson, an assistant surgeon in the army stationed at Jefferson Barracks. Scott became Dr. Emerson’s body servant or valet.

A Slave in Free Territory

On December 1, 1833, Dred Scott traveled with Dr. Emerson to Fort Armstrong, at Rock Island, in Illinois. For the first time, Scott was living in “free” territory. For the next three years, he lived and attended to Dr. Emerson’s needs at Fort Armstrong. When the fort was abandoned on May 4, 1836, Dr. Emerson was transferred to Fort Snelling on the upper Mississippi in the Wisconsin Territory, now Minnesota. Scott traveled up the Mississippi River, even farther north.

At Fort Snelling, Dred Scott met Harriet Robinson, an enslaved woman from Virginia who was about fifteen years younger than him. In either 1836 or 1837, they were married by Harriet’s enslaver, Major Lawrence Taliaferro, an Indian agent and justice of the peace. Major Taliaferro was known for respecting the rights of Native Americans. He may have sold or transferred ownership of Harriet Robinson to Dr. Emerson and married her to Dred Scott so the couple could remain together.

For the next year, Dred Scott remained at Fort Snelling with his bride. By April 1838, however, he and Harriet—who was now pregnant—were sent south to Louisiana. Dr. Emerson had been transferred to Fort Jesup and had requested that Dred and Harriet Scott join him and his new wife, Eliza Irene Sanford. Soon after making the long trip to Louisiana, the Scotts were sent to St. Louis, and then back to Fort Snelling. Harriet gave birth to their daughter Eliza Scott in free waters on the steamer Gipsey. Dred Scott remained at Fort Snelling for another two years, working for Dr. Emerson and living with his wife and infant daughter.

Back to St. Louis

During the summer of 1840, Harriet left Fort Snelling forever. Dr. Emerson had been transferred yet again, this time to Florida where the Seminole War was being fought. Harriet and her family were sent to St. Louis where they were hired out to work for other people while the Emersons collected their wages. Harriet gave birth to another daughter, Lizzie Scott, during this period of time. She most likely worked as a laundress and domestic servant. She probably worked long hours in her employer’s house, lived in quarters off the kitchen, cared for her children, but never collected any pay.

In 1843, Dr. Emerson died suddenly. Though neither Dred nor Harriet appeared in Dr. Emerson’s will, Irene Emerson considered them her property. Mrs. Emerson moved in with her proslavery father, Alexander Sanford, on his plantation near St. Louis. Her brother, John F.A. Sanford, a successful businessman, handled many of her affairs. For the next three years, Dred and Harriet Scott worked for other people while Mrs. Emerson collected their wages.

Filing a Suit for Freedom

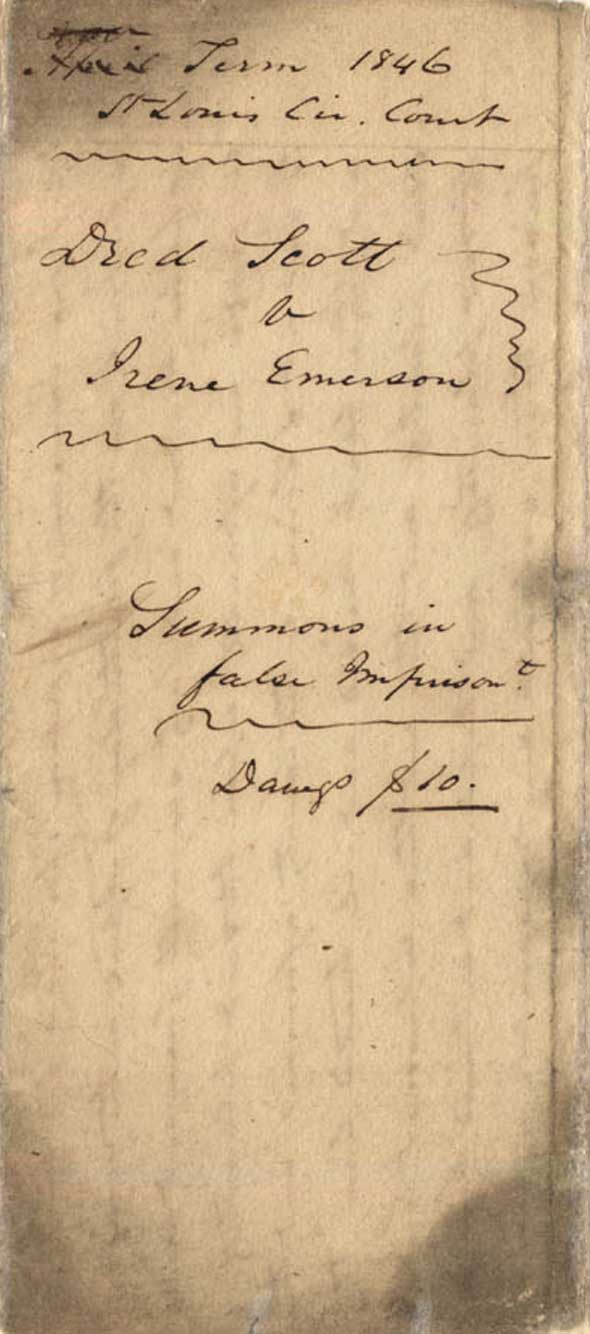

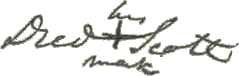

The practice of hiring out enslaved people may have been convenient for the enslaver, but it was not a positive experience for most enslaved people. On April 6, 1846, Dred and Harriet Scott each filed separate petitions in the Circuit Court of St. Louis to gain their freedom from Irene Emerson. Francis Murdock was their lawyer. Unable to read or write, Scott perhaps relied on advice from the Blow family, with whom he had renewed contact since returning to St. Louis. Additionally, Harriet Scott knew John R. Anderson, the minister of the Second African Baptist Church, who had helped other enslaved people file petitions for their freedom in Missouri courts.

It was not uncommon for enslaved people to sue for their freedom if they had lived in free states for a period of time. Dred Scott had lived in free territory for the past decade, so it seemed that his case would have a positive outcome. With the financial and legal help of the Blow brothers, Henry and Taylor, and their friends, Dred and Harriet’s cases came to trial on June 30, 1847. Unfortunately, their cases were dismissed on a technicality. Their lawyer moved for a new trial.

Irene Emerson quickly made arrangements for the Scotts to be put under the charge of the St. Louis County sheriff. For almost ten years, from March 17, 1848, until March 18, 1857, Dred Scott and his family would be in the sheriff’s custody. The sheriff was responsible for hiring out the Scotts and collecting and keeping their wages until the freedom suit was resolved.

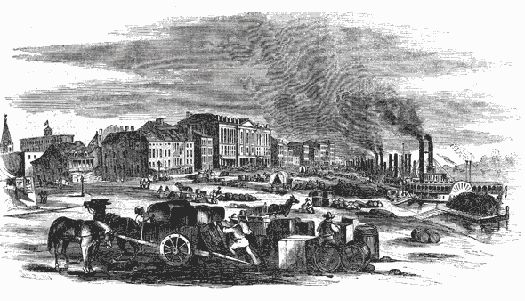

Dred Scott worked another two years as a hired out enslaved person with no income before his case came to trial again. His case and Harriet’s were delayed due to heavy court schedules, a devastating fire in St. Louis in 1849, and a subsequent outbreak of cholera. Finally, on January 12, 1850, the case was heard, and the jury ruled in favor of the Scotts. Dred Scott and his family were free.

A Long Court Battle

Unfortunately, Dred Scott’s freedom was short lived. Mrs. Emerson would not accept the court’s decision. With the assistance of her brother, Mrs. Emerson appealed her case to the Missouri Supreme Court. Before it came to trial, however, a decision was made to combine Harriet’s case with Dred’s. On February 12, 1850, the case was renamed Dred Scott v. Irene Emerson, and its outcome would apply to Harriet. Again, there was a lengthy wait before the new case went to trial.

In the meantime, Mrs. Emerson left St. Louis, moved to Springfield, Massachusetts, and married Dr. Calvin Clifford Chaffee, an antislavery congressman. Dr. Chaffee was unaware that his new wife enslaved people and that she was resisting their plea for freedom. On March 22, 1852, the Missouri Supreme Court reversed the earlier ruling. Dred Scott was still enslaved, despite his years living in free states. The “once free, always free” statute in earlier legislation was denied by proslavery judges. In this decision, the highest court in Missouri upheld the rights of enslavers over the rights of enslaved people. Tensions and outbursts over the issue of slavery were now regular occurrences throughout the nation.

Entitled to His Freedom

Dred and Harriet Scott did not give up. With the continued help of new lawyers, the Blow family, and other supporters, Dred Scott’s case moved through the Missouri courts to the highest court in the nation. At this point, John Sanford, who lived in New York, claimed ownership of the Scotts. The Scott’s new lawyer, Roswell Field, appealed the decision and added Scott’s daughters to the case. Eventually, Field arranged for the case to go before the U.S. Supreme Court. He convinced Montgomery Blair to argue for the Scotts in what became the famous Dred Scott v. Sanford case.

On March 6, 1857, Dred Scott finally received a decision about his suit for freedom. Chief Justice Roger B. Taney ruled that Scott, because of his race, was not a citizen of the United States. He had no right to bring suit in a federal court. He had never been free while living in “free states,” and the Congress had no authority to prohibit slavery. The entire Scott family was to remain enslaved.

Free at Last

Shortly after Judge Taney’s verdict, John Sanford died, and Dr. and Mrs. Chaffee transferred ownership of Scott and his family to Taylor Blow in St. Louis. Dr. Chaffee was eager to free the people his wife enslaved because he believed that slavery was wrong. Mrs. Chaffee, however, would only transfer ownership if she could collect the wages that had been held by the sheriff for the past eight years. The total amounted to about $750.

On May 26, 1857, Dred and Harriet Scott appeared in the Circuit Court of St. Louis for the last time. Taylor Blow emancipated them with papers drawn up by Arba Nelson Crane and presented to Judge Alexander Hamilton, the judge who had originally heard the case. Afterwards, Dred and Harriet Scott were interviewed, and engravings of them appeared in the June 27, 1857, edition of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper.

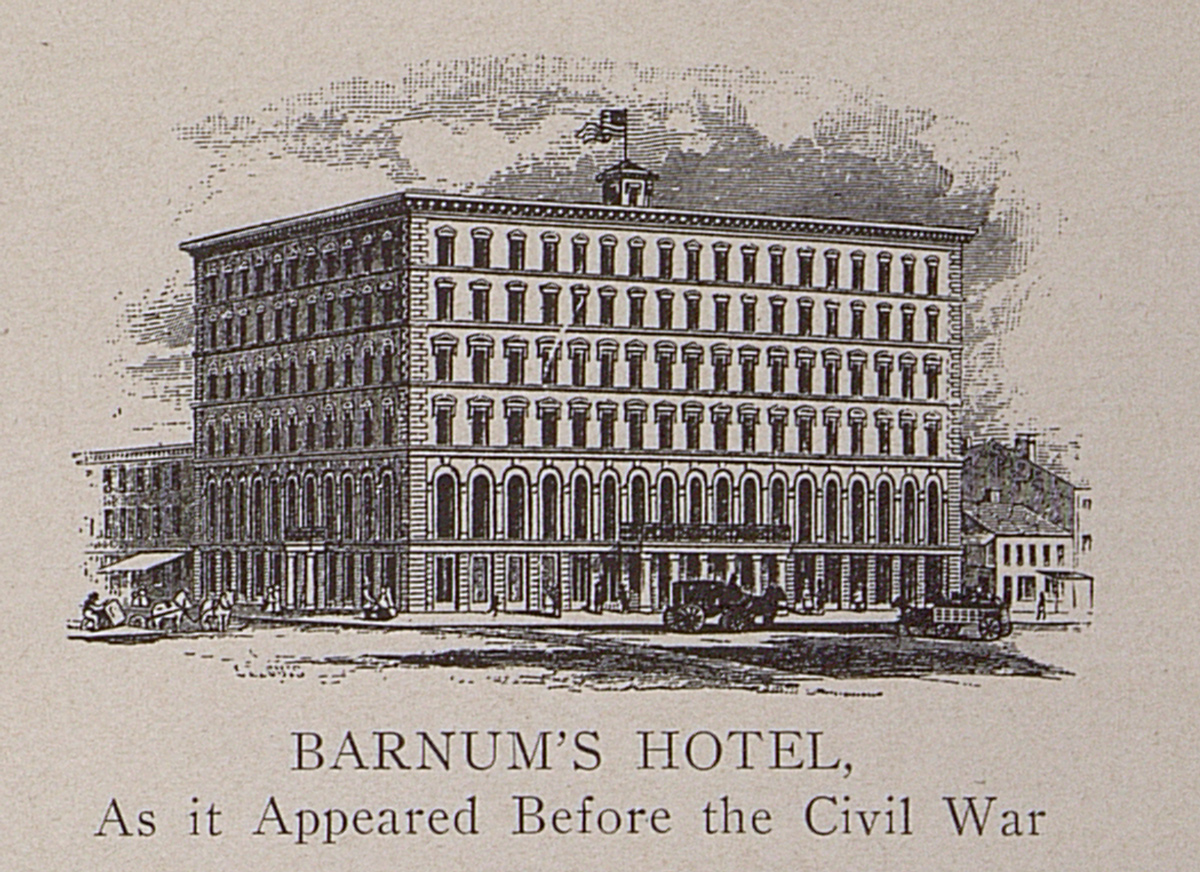

For the next year, Dred Scott worked as a porter at Barnum’s Hotel in St. Louis. He also delivered the laundry that Harriet took in as a free laundress. Scott was known by many people because of his famous freedom suit. His daguerreotype was taken during this year. Sadly, Scott became sick with tuberculosis and died on September 17, 1858, just a little more than a year after gaining his freedom.

Taylor Blow buried Dred Scott in the Wesleyan Cemetery at Grand and Laclede avenues. Later, because the cemetery had been abandoned, Blow bought a better resting place for Scott. On November 27, 1867, Blow purchased Lot 177 in Section 1 in Calvary Cemetery and had Scott reburied there. This action showed Blow’s strong regard for the man he’d known since infancy.

Legacy

Though Dred Scott did not win his freedom via the courts, his valiant fight—made possible by the assistance of friends and abolitionists—pushed America toward a bloody civil war that would eventually abolish the practice of slavery in this country.

Text and research by Carlynn Trout

References and Resources

For more information about Dred Scott’s life and career, see the following resources:

Society Resources

The following is a selected list of books, articles, and manuscripts about Dred Scott in the research centers of The State Historical Society of Missouri. The Society’s call numbers follow the citations in brackets.

Articles from the Missouri Historical Review

- Ehrlich, Walter. “Was the Dred Scott Case Valid?” v. 63, no. 3 (April 1969), pp. 317-328.

- Foley, William E. “Slave Freedom Suits Before Dred Scott: The Case of Marie Jean Scypion’s Descendants.” v. 79, no. 1 (October 1984), pp. 1-23.

- Hamm, Thomas D. “A Quaker View of Black St. Louis in 1841.” v. 98, no. 2 (January 2004), pp. 115-120.

- “One Hundredth Anniversary of the Dred Scott Decision.” v. 51, no. 4 (July 1957), pp. 425-426.

- Schwartz, Harold. “The Controversial Dred Scott Decision.” v. 54, no. 3 (April 1960), pp. 262-272.

Articles from the Newspaper Collection

- “Dred Scott Case Celebrated Here.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. March 7, 1957. [Reel # 43017]

- “Dred Scott Dead.” St. Louis Evening News and Intelligencer. September 20, 1858. [Reel # 39323]

- “Dred Scott Dead.” Liberty Weekly Tribune. October 1, 1858, pp. 1-4. [Reel # 26663]

- “Dred Scott Free At Last, Himself and His Family Emancipated.” St. Louis Daily Evening News. May 26, 1857.

- Kremer, Gary R. “Dred Scott Case to be Showcased in Archives.” Jefferson City News Tribune. January 16, 2000. [Reel # 17076]

- Price, Bob. “Slavery Issue Passed the Point of No Return 100 Years Ago.” Kansas City Star. March 5, 1957. [Reel # 21057]

- “Roswell M. Field was Attorney for Dred Scott.” Boonville Weekly Advertiser. January 22, 1886. [Reel # 1750]

Books and Articles

- “Artifacts as Storytellers: The Dred Scott Portrait.” Missouri Historical Society Magazine. Jan/Feb 2000. p. 7.

- Benton, Thomas Hart. Examination of the Dred Scott Case. New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1858. [F552 B446h in case]

- Bryan, John A. “The Blow Family and Their Slave Dred Scott, Part I.” The Bulletin. St. Louis, MO: Missouri Historical Society. v. 4, no 4 (July 1948), pp. 223-231; Part II, v. 5, no. 1 (October 1948), pp. 19-33. [REF F550 M696]

- Christensen, Lawrence O., William E. Foley, Gary R. Kremer, and Kenneth H. Winn, eds. Dictionary of Missouri Biography. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1999. pp. 295-296; 665-666; 679-681. [REF F508 D561]

- Ehrlich, Walter. They Have No Rights: Dred Scott’s Struggle for Freedom. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1979. [REF 552 Eh89]

- Ewing, Elbert William K. Legal and Historical Status of the Dred Scott Decision. Washington, DC: Cobden Publishing Company, 1909. [REF F552 EW 54]

- Fehrenbacher, Don E. The Dred Scott Case: Its Significance in American Law and Politics. New York: Oxford University Press, 1978. [REF F552 F322]

- Finkelman, Paul. Dred Scott v. Sandford: A Brief History with Documents. Boston: Bedford Books, 1998. [REF F552 F495]

- Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, June 27, 1857. [REF IHG 973.7 L565 oversize]

- Kaufman, Kenneth C. Dred Scott’s Advocate: A Biography of Roswell M. Field. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 1996. [REF F552 K62]

- Latham, Frank Brown. The Dred Scott Decision, March 6, 1857; Slavery and the Supreme Court’s Self-Inflicted Wound. New York: F. Watts, 1968. [REF IJ L347d]

- Maltz, Earl M. Dred Scott and the Politics of Slavery. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2007. [REF F552 M299]

Manuscript Collection

- The Missouri Collection (C3982)

Folder 439 contains records from the Dred Scott Case, 1852. The material consists of a facsimile of handwritten opinions of Missouri Supreme Court Justices Gamble and Scott in the case.

Outside Resources

- Africans in America PBS Series

Based on the PBS series Africans in America, this website tells the story of Dred Scott’s life and legal battle. - The Dred Scott Case

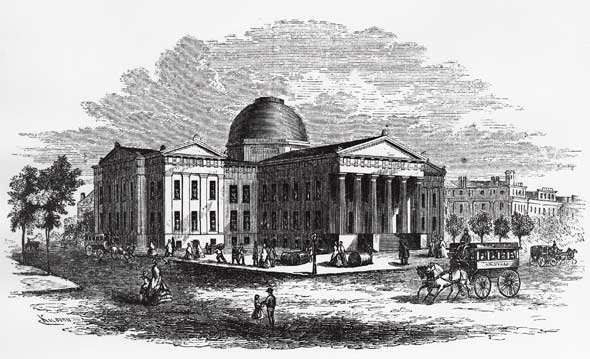

Hosted by the National Park Service, this website on the Old Courthouse in St. Louis provides information about one of its historic trials, the Dred Scott Case. - Missouri State Archives: Dred Scott: 150th Anniversary Commemoration

This Secretary of State Website offers a thorough study of the Dred Scott case as it moved through the Missouri court system and ended in the U.S. Supreme Court. Also of great interest is the link “Conservation of the Dred Scott Papers,” which shows how the State Archives restored and preserved the original court records of this case. - The Revised Dred Scott Case Collection

This comprehensive Website provides images of the actual case documentation, including petitions to the courts, writs of summons, appeals, and affidavits. A chronology of events is also included.