Emily Newell Blair

Introduction

Emily Newell Blair was a prominent suffragist, writer, activist, and elected official. She worked throughout her life to help women gain the right to vote as well as exercise their political power.

Early Years and Education

Emily Newell was born on January 8, 1877, in Joplin, Missouri, to James Patton Newell and Anna Cynthia Gray. Emily had five siblings named Jim, Anna, Julia, Margaretta, and Ella.

Emily spent most of her childhood in Carthage, Missouri, after her father was elected the Jasper County Recorder of Deeds. She attended schools that did not admit African Americans, and her mother forbade her and her brother and sisters from making friends with those outside her social class. This relative isolation from others in the community and at school led to Emily creating a very close bond with her brother Jim, who was only one year older. The two were seen together so often that they earned the joint nickname “Jimily and Emily.”

Outside of school, Emily studied piano, composition, and music theory. Since music was an important part of their life, the family regularly went to St. Louis for theater and music performances. Traveling gave Emily experiences that taught her courage and provided knowledge that later proved useful during her time in politics.

Hardship Strikes

After graduating from Carthage High School in 1894, Emily attended the Woman’s College of Baltimore (later Goucher College) in Maryland and took summer classes at the University of Missouri. She was forced to leave college in 1895, however, after the death of her father. Her sister Anna would later attend the University of Missouri and graduate in 1902.

Emily went back home to care for her younger siblings while her mother and brother ran her late father’s mortgage and insurance business. This was a very stressful time for Emily, who at just eighteen years old was taking on the responsibilities of the family as her own. Blair later said, “I went maternal. Without birth pangs I experienced motherhood.” After three years, Emily took a job in nearby Sarcoxie, Missouri, teaching physical geography, literature, and rhetoric to high school students.

Family Life

In 1900 Emily married Harry Wallace Blair, a former high school classmate. In her autobiography, she wrote that “The greatest stroke of luck I ever had was my husband.” The couple moved to Joplin, where Harry worked as a court reporter. In 1901 the couple moved to Washington, DC, so Harry could attend Columbian Law School (now George Washington University).

While in Washington, Emily gave birth to her first daughter, Harriet, in 1903. The Blairs returned to Carthage in 1905, where Emily gave birth to her son Newell in 1907.

A Writer’s Life

When Newell was three, Emily Blair decided to return to the workforce, launching her writing career in 1910 by publishing “Letters of a Contented Wife” in Cosmopolitan. In the next year, she published articles in Outlook, Lippincott, Women’s Home Companion, Harper’s Bazaar, and Cosmopolitan, mostly writing about her experiences as a wife and mother.

Inspired by the fight for women’s suffrage, Blair decided to run for president of the Missouri Women’s Press Association in 1913 and won. As president, Blair spoke to groups across Missouri in favor of women’s voting rights. She became the first editor of the suffragist magazine Missouri Women in 1914. Of this time, Emily reflected, “It was there, I think, that there came to me the thought, ambition, or temptation, whatever it was, that my life need not be bounded by the four walls of a home.”

Political Life

As Blair grew more involved in the fight for women’s suffrage, she became acquainted with prominent suffrage leader Carrie Chapman Catt through the National Women’s Suffrage Association. When Catt and Missouri suffragists met to plan a protest during the 1916 Democratic Convention in St. Louis, Blair suggested to Catt that women line the street on the way to the convention site. They would wear white, the symbolic color of the suffrage movement, and carry yellow parasols for a feminine touch.

Participants would don yellow sashes that read “Votes for Women” to silently express their beliefs. Catt took Blair’s idea and made it a reality. Thousands of women protested for women’s voting rights outside the Democratic national convention. The demonstration later became known as the Golden Lane protest.

The protest was very influential in gaining recognition for the women’s suffrage movement in the Democratic Party. Just four years later, the Nineteenth Amendment to the US Constitution was passed giving women the right to vote.

Hardship Strikes Again

While Emily Blair was starting to find success in her political career, the United States had entered World War I. Harry Blair soon went overseas to serve as a YMCA secretary for the 308th Infantry, leaving Emily to care for their two children.

Emily herself was opposed to the war, writing in her autobiography, “I was not enthusiastic about the war, for I was temperamentally a pacifist.” Yet she took a position working on the Women’s Committee of the Council of National Defense, which organized the role of women in the nation’s war effort. In this position, Blair undertook the task of writing a history of the committee.

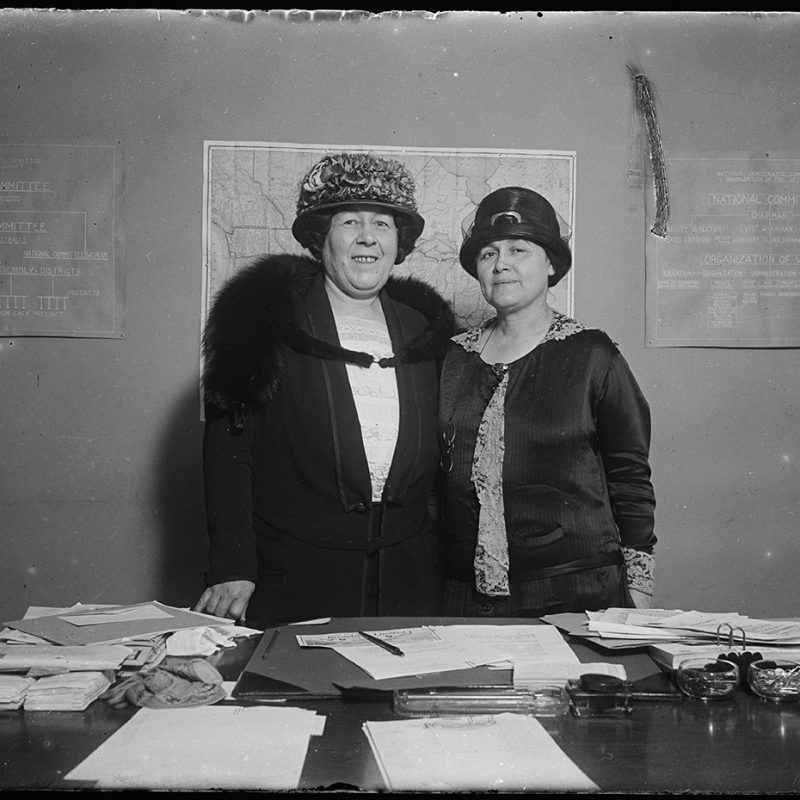

Victory in Washington

Shortly after Harry’s return from Europe, the Nineteenth Amendment was passed in 1920. This marked a high point in Emily Blair’s career, as she had worked so hard for women’s right to vote. The National Women’s Suffrage Association reorganized and renamed themselves the League of Women Voters, a group in which Blair remained involved, now as a voter. That women could now vote meant they could also hold political office. Many women decided to run for elected positions, including Blair. She ran to become Missouri’s committeewoman on the Democratic National Committee, the body that governs the Democratic Party, and won.

In February 1922, Blair was called to Washington, DC, by National Committee chair Cordell Hull to organize women within the Democratic Party. Hull and other party leaders had noticed that though women now had the right to vote, many were hesitant to become involved in politics.

Blair took this job very seriously. She played an important part in creating more than 700 Democratic women’s clubs across the country in the span of only six months in 1922. Democratic women’s clubs were a place where women could discuss their political views, organize campaigns for office, organize protests, and determine how to become involved in politics.

Because of her success as a committeewoman, Blair was encouraged to run for vice-chair of the Democratic National Committee and was elected in August 1922. Through that position, she founded the Women’s National Democratic Club in Washington, DC. She was re-elected to the position in 1924 and 1926, though she resigned in 1928 to focus on her writing career.

A Return to Writing

Blair moved back to Joplin, Missouri, and began to write again. She wrote her autobiography from 1926 to 1933, though it was not published until after her death. During this period, she worked as the associate editor of Good Housekeeping and published two books: The Creation of a Home: A Mother Advises Her Daughter (1930) and A Woman of Courage (1931). Both books focus on domestic life and traditional values.

A Return to Politics

By the early 1930s, Harry Blair’s legal practice was struggling due to the Great Depression. As Emily saw how the financial crisis was hurting families like hers, she became active in politics once again, especially when she learned about Franklin D. Roosevelt’s campaign for president. Blair was excited by Roosevelt’s ideas and worked to get him elected.

After Roosevelt’s victory, Blair hoped to boost her family’s income by moving to New York or Washington, where she could make more money as a writer. Her husband had doubts about the move, so Emily worked to get Harry a position in the government. With her help, he was appointed to a position as an assistant attorney general. Harry remained in this position until 1937 when he went back to practicing law at his own private firm, this time in Washington. Meanwhile, Emily Blair went to work for Roosevelt’s New Deal administration, becoming the chair of the Consumer’s Advisory Board of the National Recovery Administration

A Writer and Activist to the End

In 1936, Blair returned to her writing career. With the United States about to enter World War II, Blair joined the Women’s Advisory Council in October 1941 to distribute information to families of those serving in the military. She became the chief of the Women’s Interest Section in 1942, but resigned in 1944 after having a stroke. In poor health for her remaining years, she died of natural causes in Alexandria, Virginia, on August 3, 1951.

Legacy

Emily Newell Blair worked tirelessly on behalf of women’s rights her entire life. She was instrumental in the effort to pass the Nineteenth Amendment, allowing women the right to vote. With the passage of suffrage, she took advantage of her new rights and status immersing herself in politics, and becoming the first woman to be elected to a major party’s national committee. Blair’s efforts advanced the cause of women’s political involvement that continues to grow to this day.

Text and research by Anna McAnnally

References and Resources

For more information about Emily Newell Blair’s life and career, see the following resources:

Society Resources

The following is a selected list of books, articles, and manuscripts about Emily Newell Blair in the research centers of The State Historical Society of Missouri. The Society’s call numbers follow the citations in brackets.

A selected list of books, articles, and manuscripts about Emily Newell Blair in the research centers of The State Historical Society of Missouri. The Society’s call numbers follow the citations in brackets.

Articles in the Missouri Historical Review

- “Missouri Women in History: Emily Newell Blair.” v. 63, no. 1 (October 1968), inside back cover.

Articles from the Newspaper Collection

- “The Campaign Log.” Columbia Missourian. March 1, 1928. p. 4, col. 6. [Reel # 7606]

- “Champion of the Buyer: Consumers’ Complaints Go to Emily Newell Blair.” Kansas City Star. November 3, 1933. p. 21, col. 1. [Reel # 20585]

- “Mrs. Blair Is Chosen.” Daily Democrat-Tribune. August 12, 1924. p. 4, col. 3. [Reel # 16340]

- “Mrs. Emily Blair Dies.” Kansas City Times. August 4, 1951. p. 2, col. 3. [Reel # 20825]

- “Mrs. Emily Blair Resigns.” Columbia Missourian. August 27, 1927. p. 3, col. 6. [Reel # 7604]

- “Obituary.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. August 3, 1951. p. 3. [Reel # 42869]

Books and Articles

- Blair, Emily Newell. Bridging Two Eras: The Autobiography of Emily Newell Blair. Edited by Virginia Jeans Laas. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1999. [REF F508.1 B5747]

- Blair, Emily Newell. The Creation of a Home: A Mother Advises a Daughter. New York: Farrar, 1930. [REF I B5753c]

- Blair, Emily Newell. A Woman of Courage. New York: Farrar and Rinehart, 1931. [REF I B5753w]

- Christensen, Lawrence O., William E. Foley, Gary R. Kremer, and Kenneth H. Winn, eds. Dictionary of Missouri Biography. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1999. pp. 78-79. [REF F508 D561]

- Kraditor, Aileen S. Up from the Pedestal: Selected Writings in the History of American Feminism. Chicago: Quadrangle Books, 1968. [REF 396 K855]

- McMillen, Margot Ford. Into the Spotlight: Four Missouri Women. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2004. [REF F508 M228in]

- Ullmann, Frances. “Advice on Books: A Picture of Emily Newell Blair at Work.” Wilson Bulletin for Librarians. v. 5, no. 5 (January 1931), pp. 322-324. [REF I UL4]

Manuscript Collection

- Ewing Young Mitchell Jr. Papers (C1041)

The papers of a Springfield, Missouri, lawyer active in Democratic Party politics, who served as assistant secretary of commerce in Franklin Roosevelt’s first administration. The material concerns family affairs, law practice with emphasis on county indebtedness, Ozark land speculation, and Democratic politics on the state and national levels. References to Emily Newell Blair are located throughout the collection.

Outside Resources

These links will take you outside the Society’s website. The Society is not responsible for the content of the following websites:

- Driscoll, Carol. “Emily Newell Blair, Missouri’s Suffragette.” Missouri Life Magazine. July/August 2020.

- Emily Newell Blair Family Papers (MS 4342)

The Western Reserve Historical Society in Cleveland, Ohio, holds the papers of Emily Newell Blair and her family, including correspondence, diaries, and typescripts of her autobiography. - Lowell Milken Center for Unsung Heroes

This website contains a short biography on Emily Newell Blair. - Online Biographical Dictionary of the Woman Suffrage Movement in the United States

This website contains a brief biographical sketch on Emily Newell Blair. - “St. Louis women honor suffragists by re-enacting the ‘Golden Lane’ of 1916.” St. Louis Public Radio. September 3, 2016.

![Ida M. Tarbell, [1905]](https://historicmissourians.shsmo.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/master-pnp-hec-18800.jpg)