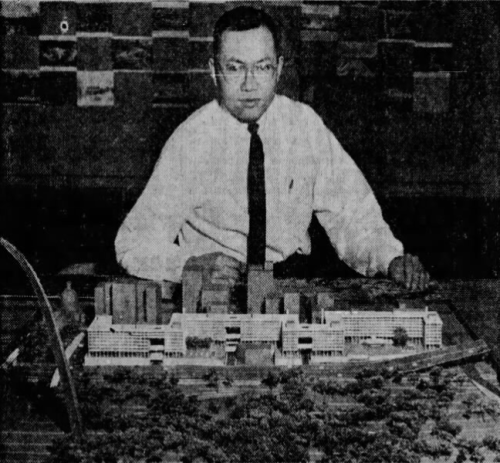

![IMG_6392 Gyo Obata, ca. 1990s. [The Temple, p. 33. SHS REF F580.293 Sa284t]](https://historicmissourians.shsmo.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/IMG_6392-300x400.jpg)

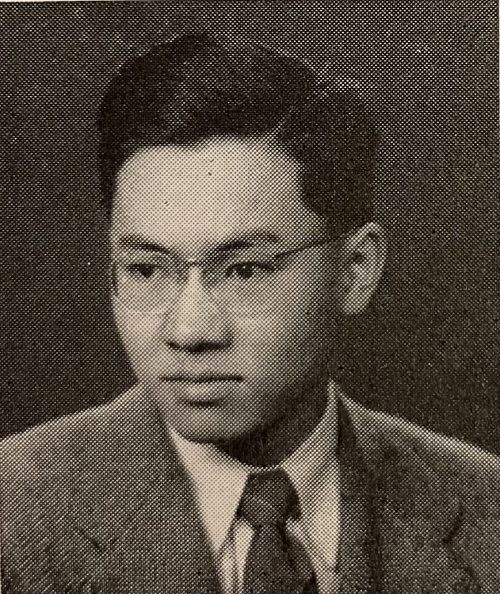

Gyo Obata

Introduction

Gyo Obata was an architect from St. Louis, Missouri. The son of artists, Obata earned praise from around the world for his work, which included notable buildings in St. Louis and other places.

Early Life

Gyo Obata was born on February 23, 1923, in San Francisco, California, to Chiura Obata and Haruko Kohashi-Obata. His father was a painter who later became a professor of art at the University of California-Berkeley. He helped to introduce Japanese sumi ink-and-brush painting on the West Coast. Gyo’s mother was an ikebana, or flower arrangement, artist. Obata’s family returned to Japan in 1928, but came back to California in 1930. Obata attended local schools and graduated from Berkeley High School in the San Francisco Bay area.

Executive Order 9066

Not long after Obata enrolled to study architecture at the University of California, Berkeley, Japan attacked the US naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on December 7, 1941, forcing the United States to enter World War II against Japan and Germany. A few weeks later, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which ordered Japanese Americans to leave their homes and live in internment camps. They were allowed to take only what they could carry with them to the camps.

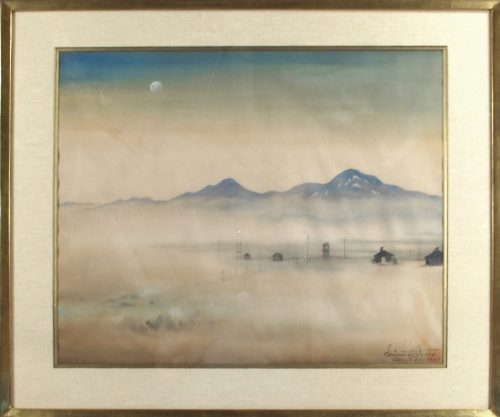

Due to Roosevelt’s order, Obata was told he would have to quit school and go with his family to a camp in Utah. But with his father’s help, he found a government program that allowed him to enroll at Washington University in St. Louis. Not long after Obata arrived in St. Louis, the rest of his family was sent to Utah. While in the internment camp there, his father completed one of his most famous paintings, Moonlight Over Topaz, Utah, which was later presented to First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. After being attacked by others in the camp for his statements against Japan, Chiura Obata was sent to live with Gyo in Webster Groves near St. Louis. At the end of World War II, he returned to teaching at the University of California, Berkeley.

Washington University

At Washington University in St. Louis, Gyo Obata quickly turned into a standout student in his architecture classes. In 1943 he became president of the university’s Architectural Society, an organization for students of interior design, architecture, and architectural engineering. He was also active in the campus YMCA and the student senate, and served as art editor for the Hatchet, the university’s yearbook. He earned a bachelor’s degree in architecture from Washington University in 1945.

A year later Obata completed a master’s degree in architecture at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan, where he was a student of Eliel Saarinen, one of America’s most prominent architects and also the father of Eero Saarinen, who designed the Gateway Arch. Years later, Obata remarked, “Saarinen’s teachings had an enormous positive influence on me. He emphasized the relationship of every element in a design and the importance of integrating them, from the smallest through the largest. Since then, I have always been interested in working on large-scale projects where many smaller parts must fit within the greater whole.”

Minoru Yamasaki

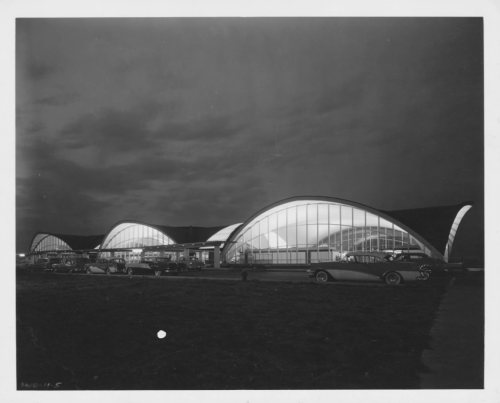

Before he embarked on a celebrated career in architecture, Obata first served in the US Army from 1946 to 1947. Upon receiving his honorable discharge, he was hired by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, an international architecture and engineering firm headquartered in Chicago, Illinois. In the early 1950s, he joined the architectural firm Hellmuth, Yamasaki & Leinweber. Led by Minoru Yamasaki, a prominent Japanese American architect, the firm was best known for the Pruitt-Igoe public housing complex in St. Louis, as well as the main terminal building at St. Louis Lambert International Airport, which Obata himself designed.

Hellmuth, Obata & Kassabaum

In 1955, Obata joined with fellow Washington University graduates George Hellmuth and George Kassabaum to form Hellmuth, Obata & Kassabaum (HOK). Based in St. Louis, the new firm turned its attention to modern building designs that helped define architectural style in the mid-twentieth century. In the early 1960s, Obata designed the Priory Chapel at the St. Louis Abbey, as well as several buildings on the newly created campus of Southern Illinois University in Edwardsville, Illinois. Obata was also responsible for designing several notable houses of worship, including Congregation Temple Israel in Creve Coeur, Missouri, Anshai Emeth in Peoria, Illinois, and the Community of Christ Temple in Independence, Missouri.

Obata is credited with significantly redesigning downtown St. Louis with structures such as the Nestle Purina PetCare Company headquarters, America’s Center Convention Complex, One Metropolitan Square, and Thomas F. Eagleton US Courthouse. Perhaps Obata’s most famous buildings in the United States designed with HOK are the James S. McDonnell Planetarium at the St. Louis Science Center, the National Air and Space Museum of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC, and the Lake Placid Olympic Center, a structure used during the 1980 Winter Olympics in Lake Placid, New York. Obata’s overseas designs include King Saud University and King Khalid International Airport in Saudi Arabia.

Legacy

Obata was still at HOK when he retired in 2012. By that time, the firm had grown from two dozen employees to more than 1,800. In the 1980s, St. Louis Post-Dispatch art and urban design critic George McCue wrote that “if you see architecture as a conversation with the surrounding environment, then Gyo is the ideal conversationalist.” Even when he was in his nineties, the world-renowned architect still kept an office at HOK in St. Louis. In 2002, the St. Louis chapter of the American Institute of Architects gave its Gold Honor Award to Gyo Obata. He received many other honors, including the Japanese American National Museum’s Lifetime Achievement Award in 2004.

Obata once reflected, “My core philosophy as an architect and as a person stems from my earliest lessons as a boy: Listen very carefully and understand what people want, work hard, and find the best ways to enhance the quality of life around you.” Gyo Obata passed away in St. Louis on March 8, 2022.

Text and research by Sean Rost

References and Resources

For more information about Gyo Obata’s life and career, see the following resources:

Society Resources

The following is a selected list of books, articles, and manuscripts about Gyo Obata in the research centers of The State Historical Society of Missouri. The Society’s call numbers follow the citations in brackets.

Articles from the Newspaper Collection

- Boeschenstein, C. K. “Gyo Obata, Designer Extraordinary: Traces His Art Heritage Back 15 Generations.” St. Louis Globe-Democrat. June 18, 1961. pp. 3F, 4F.

- Duffy, Robert W. “Look, Up in the Sky!” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. March 13, 2002. pp. C1, C7.

- Duffy, Robert W. “Yosemite Through Asian Eyes.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. January 16, 1994. pp. 3B, 8B.

- McCue, George. “Youthful St. Louis Form-Giver.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. March 6, 1960. p. 5B.

- Neman, Daniel. “Influential Architect Developed St. Louis Office into Global Force.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. March 10, 2022. pp. A1, A5.

- Peters, Frank. “How Buildings Are Born and Raised on a Video Screen.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. August 3, 1986. p. 5C.

- Woo, William F. “Conquering a $40,000,000 Challenge.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. September 6, 1964. p. 3F.

- Building the Temple: A Selection of Herald Articles. Independence, MO: Herald Publishing House, 1992 [SHS REF F580.293 Sa284b]

- Cannon, Jamie. ed. 20 Fellows: Paths Taken Lessons Learned. St. Louis: American Institute of Architects St. Louis, 2007. [SHS REF H235.18 Am3]

- Mumford, Eric. ed. Modern Architecture in St. Louis: Washington University and Postwar American Architecture, 1948-1973. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004. [SHS REF H235.15 W279]

- Preparing for the Temple: A Selection of Herald Articles. Independence, MO: Herald Publishing House, 1989. [SHS REF F580.293 Sa284]

- The Temple. Independence, MO: Herald Publishing House, 1997 [SHS REF F580.293 Sa284t]

- Washington University. The Hatchet. St. Louis: Washington University, 1944. [REF 378.778W2 V9 1944]

- Washington University. The Hatchet. St. Louis: Washington University, 1945. [REF 378.778W2 V9 1945]

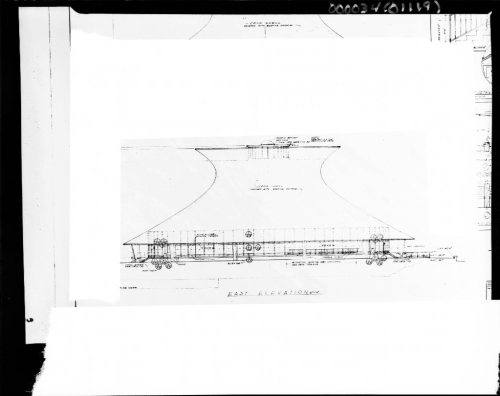

- Charles Trefts Photographs (P0034)

This collection contains images from 1900 to 1963 depicting St. Louis City and County people, public buildings, riverfront scenes, bridges, churches, catastrophes, houses and parks. Trefts photographed many historic events such as the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition; the 1934 World Series; and aviation in St. Louis including the Wright brothers at Kinloch Field in 1908 and Charles Lindbergh’s return from Paris in 1927. Also included in this collection are images of blueprints for the James S. McDonnell Planetarium designed by Gyo Obata. - George McCue Addenda (S0718)

This addenda to the George McCue Papers contains the research files compiled by St. Louis Post Dispatch urban design critic George McCue, as well as manuscripts and related documents for the books and articles he authored. Also included in the addenda are 10,918 photographs taken by McCue to document the buildings, people, and art he wrote about during his career.

Outside Resources

These links will take you outside the Society’s website. The Society is not responsible for the content of the following websites:

- A Song of Resilience

This website is hosted by ArcGIS/Washington University and includes interactive materials related to the experiences of Japanese Americans, particularly Gyo Obata and another well-known architect, Richard Henmi, in St. Louis. - HOK

This website is hosted by HOK and features a news story about Gyo Obata’s life and career. - Saint Louis Art Museum

This website is hosted by the Saint Louis Art Museum and features a blog post about Chiura Obata’s life and career.