Hazel McDaniel Teabeau

Introduction

Hazel McDaniel Teabeau was a trailblazer as an activist, scholar, and educator. In the fall of 1950, she became the first African American woman to enter the University of Missouri as a student. She made history again in 1959 when she completed a doctorate in Speech and Dramatics, becoming the first African American to earn a PhD degree from the University of Missouri.

Early Years

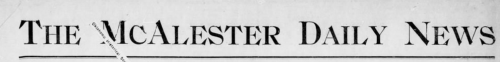

Hazel Brunette McDaniel was born in Fort Smith, Arkansas, on December 4, 1892, to Edgar E. McDaniel, a railroad worker, and his wife, Emma, a schoolteacher. Well respected in the community, Edgar was, in Hazel’s own words, a man “continually on the go.” She had an older brother, Edgar Jr., and a younger sister, Blanche, born in McAlester, Oklahoma, after Edgar Sr. took a position there as a section manager for the Choctaw Coal and Railway Company, later known as Rock Island Railroad. Edgar Jr. worked alongside his father as a postal clerk at Rock Island, but in May of 1912 he was severely injured when a passenger train crashed, overturning the mail and baggage cars. He recovered from his injuries and was able to work again as a clerk for the railroad.

Education

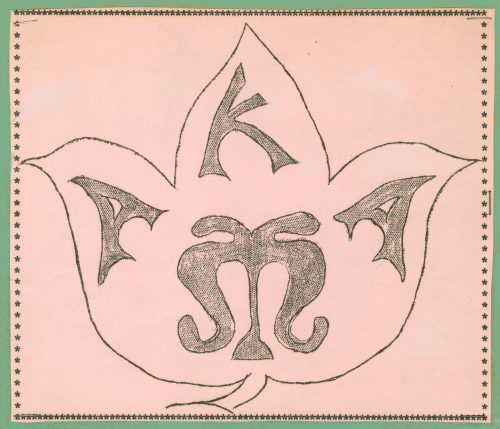

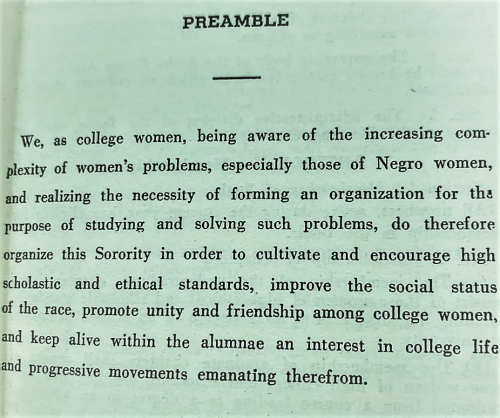

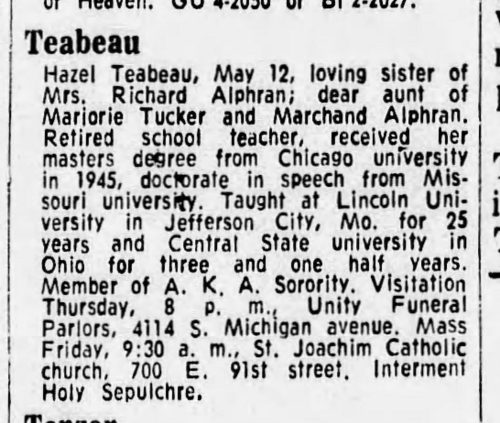

A good student, Hazel went to college and earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in English Language and Literature at the University of Kansas in 1915. At Kansas she was a founding member of the Delta chapter of Alpha Kappa Alpha, a sorority whose goals included helping Black university women to “take [their] place in the vanguard of civilization.” It was the sorority’s first chapter outside of Washington, DC, where AKA was founded at Howard University in 1908.

After graduating from the University of Kansas, Hazel returned to Oklahoma, where she worked as a schoolteacher for two years before moving to St. Louis, Missouri, for a teaching position at Sumner High School, the first high school for Black children west of the Mississippi River. Hazel’s mother and sister joined Hazel in St Louis after Mr. McDaniel died in 1919.

Activism and Family Life

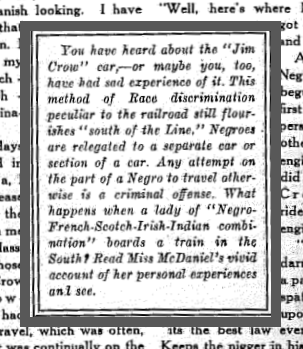

Hazel actively contributed to the Black Catholic movement of the 1920s and 1930s. In the late 1920s, Black Catholics organized and called for full equal rights within the church. The Federated Colored Catholics were founded in 1925, picking up the call for reform from the Colored Catholic Congress of the late nineteenth century. When the Black Catholic reform movement reached Missouri, Hazel used her writing talents to contribute to the cause. Her article “Miss Jim Crow” ran in the St. Elizabeth’s Chronicle, published by the St. Elizabeth Parish of the Catholic Church in St. Louis, in November 1928.

The article detailed her experience as a light-skinned Black woman who could pass as white on segregated Jim Crow trains from Kansas City to Oklahoma. She described watching as the train approached the Oklahoma border. As the Black porter tapped one dark-skinned person after another, she waited nervously. When asked about her “nationality,” Hazel replied that she “had not been accustomed to travel with a [sign] about [her] neck designating [her] nationality.” The porter apologized, and Hazel remained in her seat, uncomfortable and “mad” about the entire encounter. Her account offers powerful insight into the African American public experience in the first half of the twentieth century.

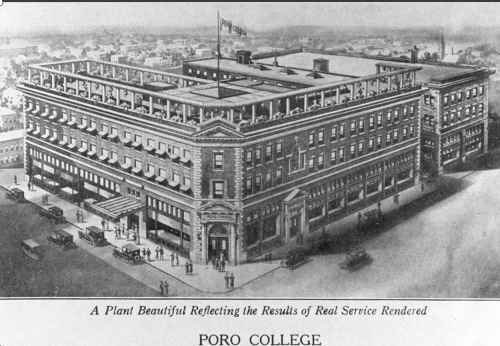

In December of 1929, Hazel McDaniel married Dr. Ralph Teabeau, a dentist, military officer, and sports promoter originally from Keokuk, Iowa. The Associated Negro Press wire service carried the story of the engagement announcement to many Black newspapers. Her mother and brother hosted the wedding at Poro College, in St. Louis, on the lush rooftop garden. Edgar Jr. was employed by then with the successful St. Louis hair care entrepreneur Annie Turnbo Malone. Malone’s Poro College was a large commercial complex with business offices, a cosmetology school, a product distribution factory, and an auditorium.

In recognition of their close relationship, Hazel and her sister Blanche married their husbands in a double ceremony surrounded by hundreds of their friends, family, and colleagues. A notice, shared widely throughout the Black press, captured the buzz and excitement of the event, noting that prominent members of “St. Louis society” enthusiastically attended a week of events related to the weddings, providing the “Misses McDaniel[s] with useful and costly gifts.” The article noted that Hazel and Ralph would continue to live in St. Louis, while Blanche and her husband, Richard Alphran, planned to move to Chicago, Illinois.

Before marriage, Hazel and Blanche had worked as English teachers at the newly built Vashon High School in St. Louis. Named in recognition of George Boyer Vashon, the first Black graduate of Oberlin College in Ohio, and his son, John B. Vashon, a beloved St. Louis educator, the high school had been built in 1927 with community support and the backing of the St. Louis Board of Education. Vashon was the city’s second high school built for African American students.

After her marriage, Hazel Teabeau continued her writing. On August 7, 1930, a piece she wrote was published in the Oklahoma City Black Dispatch. “My Place in the Sun” was an ode about wanting to live in the world without fear, ridicule, and violent death. Calling for “freedom” from labels and a life as “just a human being,” “not negro,” and “not wench,” the poem calls for space to “stroll the water’s edge, my lover and me, Hand in hand, enjoying silences together.” Unlike her earlier article “Miss Jim Crow,” which could be read as an autobiographical account, “My Place in the Sun” reads more like Romantic period poetry.

In September 1932, when the Federated Colored Catholics convened for their eighth annual meeting under the new name National Catholic Federation for the promotion of Better Race Relations, Teabeau drafted an article reporting the event’s significance. At the time, the organization boasted 100,000 members and was the only group dedicated exclusively to Black Catholics. The name change represented a shift to an interracially governed body aimed at reforming the church from within. Teabeau served as the associate editor of the organization’s monthly publication, the Interracial Review.

Lincoln University Years

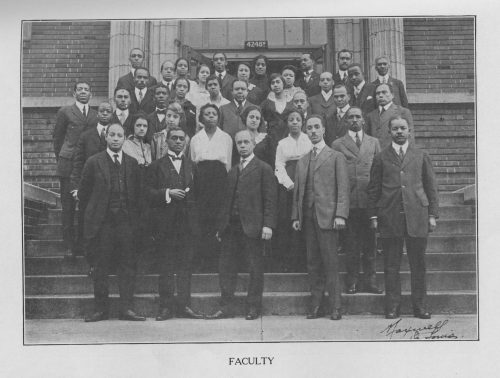

Teabeau joined Lincoln University in Jefferson City, Missouri, in 1937 after spending a year teaching English at Wilberforce University in Ohio. She was hired as an instructor, and later Professor of English, working closely with Thomas D. Pawley III in the Theatre and Dramatics department. She was known as a woman of great intellect and integrity among her colleagues.

While at Lincoln, Teabeau was a member of the American Association of University Professors (AAUP), the University Stage Crafters organization, a founding member of Gamma Epsilon Omega chapter of the AKA sorority, and a spokesperson for the group. When Lincoln professors gave Negro History Week, which later grew into Black History Month talks across the state, Teabeau spoke to students and teachers in Columbia, Missouri, on the subject “Let Us Live, Think, and Act Like Freemen.”

Teabeau took a year away from Lincoln in 1944 to complete a Master of Arts in English degree at the University of Chicago. In 1947 she accepted an appointment as editor of the Missouri Social Workers Association’s publication Building a Better State. Teabeau was reelected to the position four years in a row. When Henry Wallace, a third-party candidate for president, campaigned in Columbia in 1948, Teabeau introduced him to a contentious crowd of protesters.

University of Missouri Integration

In September of 1950, Teabeau became one of the first Black students at the University of Missouri, and in 1959 she became the first Black person to earn a doctorate there. After losing a case challenging its segregationist admissions policy in Cole County court in 1950, MU’s Board of Curators voted to begin admitting Black Missouri residents when the classes they wanted to take were unavailable at Lincoln University, the state’s university for Black students. The University of Missouri admitted Teabeau, Gus T. Ridgel, and Samuel Jones to the graduate school in Columbia while Elmer Bell Jr. and George Everett Horne were admitted to the Rolla campus.

While at the University of Missouri, Teabeau continued to break barriers. In 1952, she was awarded the McAnally Medal for her paper “From the Cycle of the West.” The McAnally award dates to 1881 and is the university’s oldest literary prize.

Legacy

After graduating from the University of Missouri with a Ph.D. in Speech and Dramatics, Teabeau returned to Lincoln University, where she continued to build a reputation as a brilliant scholar and activist who was always ready to take on any challenge. Mentee and retired Lincoln professor Ouida Sprye Tolbert gleefully remembered Teabeau fifty-four years after her death as a “master at whatever she did. . . . She was the kind of Professor who gave a spark to anything she did, [a] master spark to anything she did.”

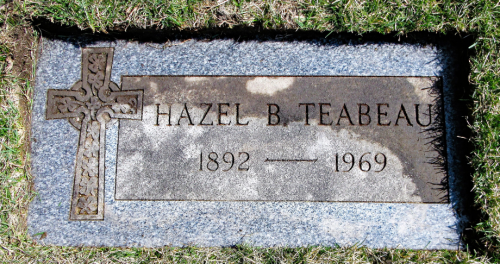

Hazel McDaniel Teabeau died in Chicago, Illinois, on May 12, 1969, at the age of seventy-six. She is buried in Holy Sepulchre Cemetery in Alsip, Illinois.

Text and research by Bridget D. Haney

References and Resources

For more information about Hazel Teabeau’s life and career, see the following resources:

Society Resources

The following is a selected list of books, articles, and manuscripts about Hazel Teabeau in the research centers of The State Historical Society of Missouri. The Society’s call numbers follow the citations in brackets.

Articles from the Newspaper Collection

The Lincoln Clarion Archive – Newspapers.com

“Alumni group meets.” Lincoln University Clarion. February 23, 1945. p.4.

“Lectures on Negro history.” Lincoln University Clarion. February 13, 1948. p.3.

“Local organizations to celebrate ‘History’ week.” Lincoln University Clarion. February 27, 1948. p.1.

“Mrs. Teabeau reviews ‘Knock on Any Door.'” Lincoln University Clarion. March 19, 1948. p.2.

“Teabeau smacks bi-partisanism.” Lincoln University Clarion. May 7, 1948. p.1.

“L.U. Faculty Members Advocate Rest Theory for Passing Exams.” Lincoln University Clarion. January 20, 1956. p.1.

Black History Project Collection, [So201]

This National Historical Publications and Records Commission funded project collected historical source material documenting the African-American experience in St. Louis. The project developed a slide presentation and held three conferences on St. Louis African-American history from 1981 to 1983. The collection includes correspondence, reports, surveys, biographical information, and a slide show.

Missouri Association for Social Welfare Records, [C3475]

Records of an association organized to improve and extend the health and welfare of the people of the State of Missouri and to promote the improvement of public and private social services and the prevention of poverty, crime, and disease in the state. The records consist of correspondence, minutes, committee records, newsletters, and conference materials.

The Maroon and White. Sumner High School, St Louis, Missouri. 1918.

Outside Resources

Brooks, Michelle. “Hazel McDaniel Teabeau: Trail-Blazing Student, Civil Rights Advocate, Exacting Professor.” Interesting Women of the Capital City. Self-published. Michelle Brooks, 2021.

“Hazel McDaniel-Teabeau, Doctoral Candidate,” Dr. Loren Reid Papers, (A74-32), University Archives, University of Missouri – Columbia.

“Hazel M. Teabeau.” Vertical File Collection, Inman E. Page Library, Lincoln University, Jefferson City, Missouri.

Lincoln University Picture Collection, (LUPC: R18), Lincoln University, Jefferson City, Missouri.

McDaniel, Hazel, B. “Miss Jim Crow.” St Elizabeth’s Chronicle. v.1, no. 9, (November 1929), pp.599.

Teabeau, Hazel, M. “My Place in The Sun.” The Black Dispatch. August 7, 1930. newspapers.com (accessed February 22, 2023)