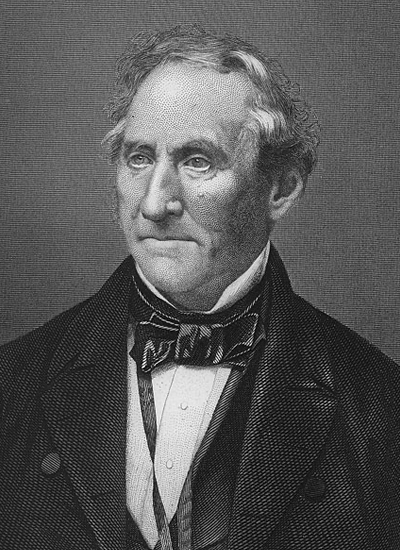

Senator Thomas Hart Benton

Introduction

Senator Thomas Hart Benton was a prominent lawyer and political leader during the first half of the 1800s. During his five terms as a U.S. senator, Benton played a major role in many national debates. He was a strong supporter of the use of hard money and westward expansion. Benton also fought against the extension of slavery into the territories.

Early Years and Education

Thomas Hart Benton was born in Hillsborough, North Carolina, on March 14, 1782. He was the first son of Jesse Benton and Ann Gooch. When Thomas was eight years old, his father, a well-respected attorney, died of tuberculosis.

At the age of sixteen, Benton was admitted to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. While he studied hard and was elected to the school’s Philanthropic Society, Benton soon got into trouble. During a quarrel, Benton came close to shooting another student. A few weeks later, he was accused of stealing money from his roommates and was expelled.

Benton returned home and in 1801 moved with his family to Tennessee. He worked on the family farm, taught at a local school, and studied law. In the summer of 1806, Benton passed the Tennessee bar exam and began practicing law.

Early Political Career and Military Service

In 1809, at the age of twenty-seven, Benton was elected to the Tennessee legislature. During his one term, he led judicial reforms, helped pass legislation that secured the right for enslaved people to have a trial by jury, and headed the legislative committee on lands. After his term ended, Benton returned to the practice of law.

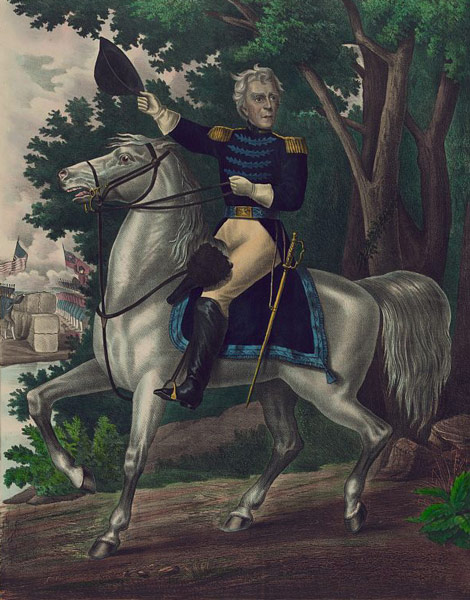

During the War of 1812, Benton volunteered for military service and was appointed a colonel in the Tennessee State Militia. He traveled throughout the United States under the direction of Colonel Andrew Jackson, a well-known political figure in Tennessee.

Benton’s two years in the military were a disappointment to him. He never saw combat. In addition, he and his brother Jesse became entangled in a quarrel with the Carroll family and Jackson. The feud ended in a street brawl in Nashville where Benton shot Jackson in the arm. Jackson survived the wound, but the two remained enemies for several years. The quarrel damaged Benton’s reputation in Tennessee. After he was discharged from the military, he decided to move west.

A Move to the Missouri Territory

In the fall of 1815, Benton boarded a riverboat and traveled to St. Louis in the Missouri Territory. He later described himself as an adventurer ready to begin on a new theatre. When Benton arrived in St. Louis, it was a small town with wood and stone buildings lined along three muddy streets. Benton resumed practicing law and soon became involved in the city ‘s business community. At the Bank of St. Louis, Benton met two important men, Charles Gratiot and Rene Chouteau. They introduced him to other important figures in the city, and he quickly became a community leader.

While practicing law, Benton often argued cases against Charles Lucas, a competing attorney. During a heated argument in court in 1817, Benton believed Lucas insulted his honor. He challenged Lucas to a duel, and the pair met on Bloody Island near St. Louis. While the duel ended with no serious injuries, Benton was still upset and requested another duel. In the second duel, Benton killed Lucas with a gunshot to the heart. After this tragic incident, Benton vowed never to duel again.

Benton tried new ventures after his move to Missouri. In 1818 he founded the St. Louis Enquirer. Benton used his newspaper to launch a political career. He took strong stances on political issues and earned the respect and attention of many Missourians.

Throughout 1819 Benton wrote editorials promoting westward expansion and Missouri statehood.

Senator Benton and Missouri Statehood

In August 1820, as the Missouri Territory inched closer to statehood following the Missouri Compromise, Benton was elected to the U.S. Senate, the start of a thirty-year career in that chamber.

Benton quickly established himself as an eloquent and powerful speaker and earned the respect of many fellow senators. Because Missouri was not yet a state, Benton was denied full membership in the Senate when he first arrived. In spite of the 1820 Missouri Compromise, disagreements over slavery and the presence of free blacks in Missouri erupted in Congress. Not until August 10, 1821, was Missouri admitted as the twenty-fourth state.

Benton married Elizabeth McDowell on March 20, 1821, in Virginia. She was the daughter of an old family friend. The couple set up their home in St. Louis and started a family. The first of their six children was born in 1822. Daughter Jessie, born in 1824, married John C. Frémont, an explorer of the American West.

"Old Bullion" in the Senate

When he returned to Washington, DC, Benton plunged back into his job. He attempted to represent a variety of local interests within Missouri such as the fur trade, men who wanted the old Spanish land titles approved, and the lead mining industry. He also introduced legislation that would decrease the sales price of public land the longer it remained unsold.

As the 1824 election approached, Benton became involved in the presidential campaign. He initially supported Henry Clay, a cousin by marriage. After Clay was eliminated from the race, Benton decided to support Andrew Jackson. While he and Jackson had resolved their differences by this time, Benton also recognized Jackson’s popularity in Missouri. Although Jackson lost to John Quincy Adams, Benton helped him win the presidential election four years later.

Benton represented Jackson’s interests on the floor of the Senate. The pair worked tirelessly on banking reforms, and many attribute the success of Jackson’s presidency to Benton. During the 1830s Jackson supported Benton as he fought for hard money in the form of gold and silver coins instead of paper money and bank notes. Benton’s stance on currency earned him the nickname “Old Bullion.”

In the 1840s the status of the Oregon Territory became an important issue. Benton did not voice any strong opinions on the matter until May 1846 when he spent three days addressing “The Oregon Question.” He continued to believe in westward expansion, more commonly called Manifest Destiny, and set out to show “the true extent and nature of our territorial claims beyond the Rocky Mountains.” At the end of his final speech, Benton moved to reintroduce a bill to declare the Oregon Territory under U.S. rule. He had first presented the bill in a secret session of Congress in 1828. The area, also claimed by Great Britain, eventually became a U.S. territory in 1848.

Fighting Against Slavery

During his years as a senator, Benton became concerned that the issue of slavery would divide the country. He had pushed for Missouri to be admitted as a slave state, viewing the abolition of slavery as dangerous to the union and harmful to Black people.

Around 1835 Benton slowly began to change his views. While he did not view slavery as wrong or wish to abolish it completely, he did not want to see it spread into the territories.

In 1849 Benton traveled around Missouri delivering speeches on slavery. In Jefferson City, he declared, “My personal sentiments, then, are against the institution of slavery, and against its introduction into places in which it does not exist. If there was no slavery in Missouri today, I should oppose its coming in.”

Benton spent his last session in Congress speaking against slavery. This change in position cost Benton much support, and he lost the 1851 senatorial election.

Final Years

Many people tried to convince Benton to campaign for president in 1852, but he instead chose to run for the U.S House of Representatives. He served one term but was not reelected. Benton ran for governor in 1856, suffering an embarrassing loss. Both of these defeats were likely due to his changed views on slavery.

In 1854 Benton’s wife, Elizabeth, died, leaving him heartbroken. To distract himself from his grief, he undertook a long lecture tour across the U.S. from 1856 to 1857. He gave lectures on slavery, warning listeners of terrible consequences if the North and South did not end their dispute.

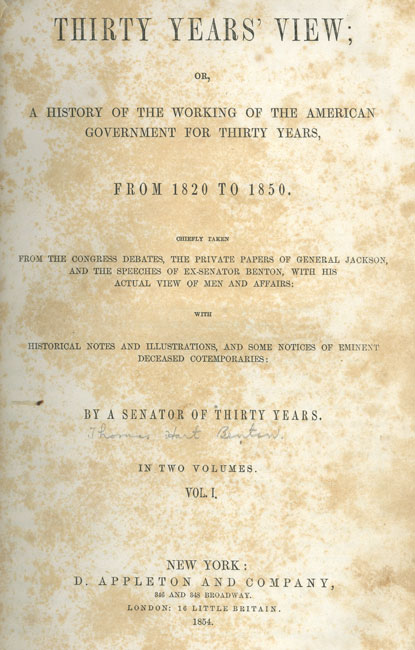

After the lecture tour was over, Benton settled into a home in Washington, DC. He devoted the next two years to writing Thirty Years’ View, a commentary on the national political scene during his time as a senator. On April 10, 1858, Benton passed away after a long fight with cancer. Large memorial services were held in both Washington, DC and St. Louis, where Benton was buried in Bellefontaine Cemetery.

Benton's Legacy

Thomas Hart Benton played a major role in shaping Missouri and the United States. He was the most influential Missouri politician during his thirty years as a senator. Benton also had an impact on the westward expansion of the country.

In 1864 the U.S. government asked each state to send statues of two citizens known for their distinguished civil or military service for the National Statuary Hall. Missouri selected Benton and Francis Blair Jr., and their statues are currently on display in the U.S. Capitol. A park in St. Louis was named after Benton in 1866. Two years later a statue of Benton sculpted by Harriet Hosmer was placed at the center of Lafayette Park in St. Louis.

Text and research by Melanie Tague and Elizabeth E. Engel

References and Resources

For more information about Senator Thomas Hart Benton’s life and career, see the following resources:

Society Resources

The following is a selected list of books, articles, and manuscripts about Senator Thomas Hart Benton in the research centers of The State Historical Society of Missouri. The Society’s call numbers follow the citations in brackets. All links will open in a new tab.

Articles from the Missouri Historical Review

- Hansen, William A. “Thomas Hart Benton and the Oregon Question.” v. 63, no. 4 (July 1969), pp. 489-497.

- McCandless, Perry. “The Political Philosophy and Political Personality of Thomas Hart Benton.” v. 50, no. 2 (January 1956), pp. 145-158.

- McCandless, Perry. “The Rise of Thomas H. Benton in Missouri Politics.” v. 50, no. 1 (October 1955), pp. 16-29.

- McClure, C. H. Early Opposition to Thomas Hart Benton. v. 10, no. 3 (April 1916), pp. 151-196.

- Merkel, Benjamin C. “The Slavery Issue and the Political Decline of Thomas Hart Benton, 1846–1856.” v. 38, no. 4 (July 1944), pp. 388-407.

- Morton, John D. “‘A High Wall and a Deep Ditch’: Thomas Hart Benton and the Compromise of 1850.” v. 94, no. 1 (October 1999), pp. 1-24.

- Morton, John D. “‘This Magnificent New World’: Thomas Hart Benton’s Westward Vision Reconsidered.” v. 90, no. 3 (April 1996), pp. 284-308.

- Ray, P.O. “The Retirement of Thomas H. Benton from the Senate and Its Significance, Part I.” v. 2, no. 1 (October 1907), pp. 1-14.

- Ray, P.O. “The Retirement of Thomas H. Benton from the Senate and Its Significance, Part II.” v. 2, no. 2 (January 1908), pp. 97-111.

- Sayles, Stephen. “Thomas Hart Benton and the Santa Fe Trail.” v. 69, no. 1 (October 1974), pp. 1-22.

Books and Articles

- Benton, Thomas Hart. Thirty Years’ View. New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1854-56. [REF I B466 In Case v. 1-2]

- Chambers, William Nisbit. Old Bullion Benton, Senator from the New West: Thomas Hart Benton, 1782-1858. Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1956. [REF F508.1 B446co]

- Christensen, Lawrence O., William E. Foley, Gary R. Kremer, and Kenneth H. Winn, eds. Dictionary of Missouri Biography. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1999. pp. 59-61. [REF F508 D561]

- McClure, Clarence Henry. Opposition in Missouri to Thomas Hart Benton. Nashville: George Peabody College for Teachers, 1926. [REF F572 M132o]

- Meigs, William M. The Life of Thomas Hart Benton. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1904. [REF F508.1 B446me]

- Mueller, Ken S. Senator Benton and the People: Master Race Democracy on the Early American Frontiers. DeKalb, IL: NIU Press, 2014. [REF F508.1 B446mue 2014]

- Roosevelt, Theodore. Thomas Hart Benton. New York: Haskell House, 1968. [REF F508.1 B446ro 1968]

- Smith, Elbert B. Magnificent Missourian: The Life of Thomas Hart Benton. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1958. [REF F508.1 B446s]

Manuscript Collection

- Benton, Thomas Hart (1782-1858), Campaign Handbill, 1854 (C2842)

Benton campaign literature from congressional election of 1854. - Benton, Thomas Hart (1792-1858), Letter, 1820 (C1459)

Benton discusses political strategy, Bank of Missouri, roads, Alabama public lands, national versus sectional interests, James Bates, and David Barton. - Benton, Thomas Hart (1782-1858), Letter, 1829 (C3576)

Written twelve days before the inauguration of Andrew Jackson. States that it will take time to see what policy the new administration will follow on appointments. - Benton, Thomas Hart (1782-1858), Letter, 1836 (C1876)

Copy of a letter announcing a renewed fight against the Bank of the United States. - Benton, Thomas Hart (1782-1858), Letter, 1838 (C1847)

Letter concerning the censure of Richard Gentry’s Missouri troops in the Seminole War and the appointment of Gentry’s widow as a postmistress. - Benton, Thomas Hart (1782-1858), Papers, 1804-1811 (C1458)

The papers include a copy of a letter to merchants John and N.P. Hardeman of Franklin, TN, requesting they send him specific books, personal items and, periodically, a statement of his account. Also included in the collection is Benton’s memorandum book of Tennessee legal cases, 1810-1811. - Benton, Thomas Hart (1782-1858), Papers, 1850-1852 (C1466)

Benton’s certified statements in the slander suit against him by James H. Birch, in the Clay County Circuit Court, Liberty, MO. - Benton, Thomas Hart (1782-1858), “Some Account of Some of the Bloody Deeds of General Jackson,” 1828 (C2865)

Articles written by Thomas Hart Benton recounting murderous actions allegedly committed by Andrew Jackson.