Lucile Bluford

Introduction

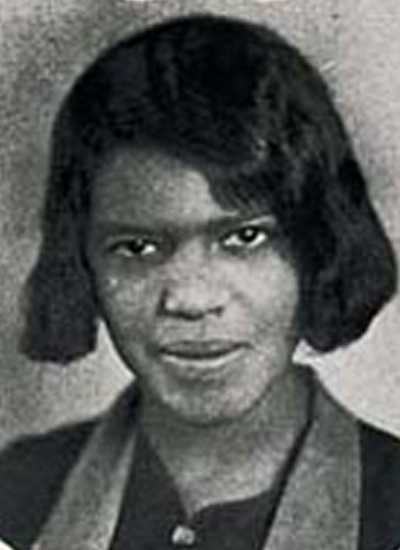

Lucile Bluford was a well-respected editor and publisher of the Kansas City Call, an important African American weekly newspaper. She was also a brave and persistent civil rights activist. In both her personal life and her career, she refused to remain quiet about racial injustice.

Early Years

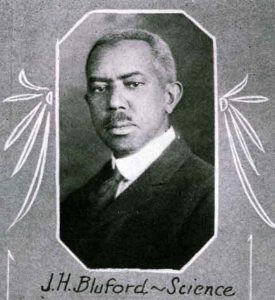

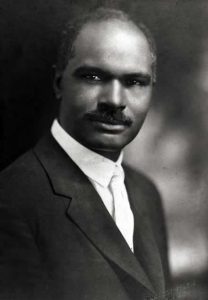

Lucile Harris Bluford was born on July 1, 1911, in Salisbury, North Carolina. Her parents were John Henry Bluford, Sr. and Viola Harris Bluford. She had two brothers, John Jr. and Guion. When Lucile was only four, her mother died. Her father later married Addie Alston, and in 1918 he accepted a position teaching science at Lincoln High School in Kansas City, Missouri. Lucile moved with her family to Kansas City when she was seven years old.

At this time in America, schools throughout the South and bordering states like Missouri had a “separate but equal” rule in education. This meant that children of different races could not go to school together. Black students attended schools that were supposed to be equal in quality to the white schools, but most of them did not have the same resources. Lucile attended Wendell Phillips Elementary. At age 13, she started Lincoln High School, where her father taught. Lucile was a very active and successful student. She wrote for the school newspaper and graduated first in her class in 1928.

Lucile discovered while working on the high school newspaper and yearbook that she wanted to become a journalist. She thought about where she could go to college to study journalism, but her choices were very limited. She knew she couldn’t attend the University of Missouri in Columbia, which had the oldest and most respected journalism school in the country. It wouldn’t admit African Americans. Black students were supposed to study at the historically black college, Lincoln University, in Jefferson City, but it did not have a journalism program. So Lucile attended the University of Kansas in Lawrence instead. She graduated in 1932 with high honors.

Lucile Bluford began her journalism career in Atlanta, Georgia, where she was a reporter for the Daily World, an African American newspaper. Returning home, she worked at the Kansas City American and then at the Kansas City Call, both African American-owned newspapers. At the Call, Bluford worked for Chester A. Franklin and advanced from the position of reporter to city editor, managing editor, and finally to editor and publisher.

Parents' Obituaries

Testing an Unfair System

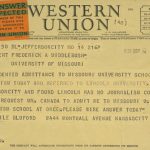

In 1939, Bluford applied to the University of Missouri School of Journalism to do graduate work. She was accepted into the program, but when she went to Columbia to enroll, she was turned away. University officials had not known that she was African American. Just the year before, Lloyd Gaines an honors student from Lincoln University, had sued the University of Missouri to be accepted into its School of Law. After his case went to the United States Supreme Court and the court ruled in his favor, Gaines mysteriously disappeared.

With the help of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Bluford strove to break down the system of injustice against African Americans in higher education. She believed that education was the key to advancement and equal treatment in society. She tried eleven times to enter the University of Missouri. She filed the first of several lawsuits against the university on October 13, 1939. Bluford’s case was denied time and time again.

In 1941 the state supreme court finally ruled in Bluford’s favor. The University of Missouri had to admit her because no equal program existed at Lincoln University. In response, the School of Journalism closed its graduate program. It claimed that it could not operate properly because a majority of its professors and students were serving in World War II.

Though Bluford ended her legal battle with the University of Missouri, she kept fighting racism. She became a leading voice in the civil rights movement in Kansas City and helped make the Call one of the largest and most important black newspapers in the nation. Eventually, the University of Missouri honored her. In 1984, a year after her nephew Guion S. Bluford, Jr. became the first African American astronaut in space, Bluford received an Honor Medal for Distinguished Service in Journalism from the School of Journalism. In 1989 the university gave her an honorary doctorate. Bluford said that she accepted the degree “not only for myself, but for the thousands of black students” the university had discriminated against over the years.

Legacy

Through her bold stands, her determination to expose racism, and her clear and forceful journalistic writing, Lucile Bluford helped change the way African Americans are treated, especially in the area of higher education.

She died in Kansas City on June 13, 2003, at the age of 91, having worked at the Call for seventy years. She is buried in Forest Hills Cemetery in Kansas City.

Text by Carlynn Trout with research assistance by Karla Sue Wentzle and Jillian Hartke

References and Resources

For more information about Lucile Bluford’s life and career, see the following resources:

Society Resources

The following is a selected list of books, articles, and manuscripts about Lucile Bluford in the research centers of The State Historical Society of Missouri. The Society’s call numbers follow the citations in brackets.

Articles from the Newspaper Collection

- “Bluford Blazed Trail in Civil Rights; Former Editor of Newspaper Dead at 91.” Columbia Daily Tribune. June 15, 2003. p. 1. [Reel # 8719]

- “Missouri Supreme Court Rules in Bluford Case.” Kansas City Call. July 18, 1941. p. 7. [Reel # 18758]

- “Ruled in Favor of Missouri Negress: Lucile Bluford is Entitled to Enroll at U. of M. School of Journalism.” The Chillicothe Constitution Tribune. July 8, 1941. p. 6. [Reel # 6293]

- Tammeus, Lisen. “Unlocking Segregation.” Columbia Missourian. February 28, 1993. pp. 1G–2G. [Reel # 7922]

Books and Articles

- “11 Honor Medalists Named By School of Journalism.” Missouri Press News. v. 52, no. 4 (April 1984), pp. 11-12. [REF F565 m691]

- Dains, Mary K., ed. Show Me Missouri Women: Selected Biographies. Kirksville, MO: Thomas Jefferson University Press, 1989. v. 1, pp. 140–41. [REF F508 Sh82]

- “KC Call Observes 75th Anniversary.” Missouri Press News. v. 63, no. 1 (January 1995), p. 19. [REF F565 m691]

- Kremer, Gary. “Segregated Education Gave Lincoln University Law and Journalism Schools.” Heartland History: Essays on the Cultural Heritage of the Central Missouri Region. St. Louis: G. Bradley Publishing. 2001. v. 2, pp. 28–30. [REF F626 K881]

- The Lincolnian. Kansas City: Lincoln High School. Senior class, 1928. [H128.851 L638]

- “Lucile Bluford: Editor and Activist.” Missouri Press News. v. 55, no. 7 (July 1987), p. 10. [REF F565 m691]

- McCandless, Perry, and William E. Foley, eds. Missouri Then and Now. 3rd ed. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2001. p. 317. [F550 M126M 2001]

- Trout, Carlynn. Notable Women of Missouri. Columbia, MO: Columbia, Missouri Branch of the American Association of University Women in partnership with Eugene Field Elementary School, Columbia, MO, 2005. [REF F508 T758 2005]

Manuscript Collection

- University of Missouri, President’s Office, Papers, 1892-1966 (C2582)

DIGITIZED MATERIALS

Papers from the administrations of several University of Missouri presidents. The collection includes correspondence from Lucile Bluford in folders 2543 and 2602-2606. - University of Missouri, Graduate School, Records, 1911-1967 (C3354)

Minutes of graduate committees, 1911-1967, and correspondence of the dean of the Graduate School with administrators, graduate faculty, graduate students, government officials, foundation officers, and alumni, 1930-1967. This collection also contains correspondence from Lucile Bluford in folders 293, 294, 401, 403, and 404. - Women in Journalism Oral History Project, Records, 1987-1994 (C3958)

The records of the Washington Press Club Foundation’s Women in Journalism Oral History Project contain transcripts from oral history interviews conducted with female journalists, including Lucile Bluford.

Outside Resources

These links, which open in another window, will take you outside the Society’s website. The Society is not responsible for the content of the following websites:

- The African American Registry

This website gives biographical information about Lucile Bluford. - Chicken Bones: A Journal for Literary & Artistic African-American Themes

This website features an article about Lucille Bluford and contains a 1941 press release announcing the court judgment upholding the Missouri law excluding African Americans from the University of Missouri. - The Unforgettable Miss Bluford

This site offers an article by journalist Pam Johnson about Lucile Bluford.