Clarence Earl Gideon

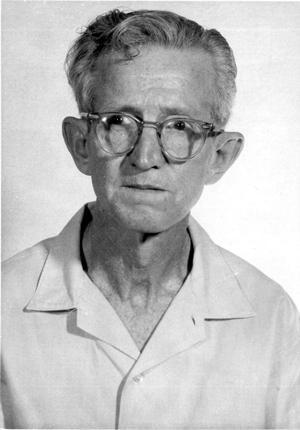

Clarence Earl Gideon was a career criminal whose actions helped change the American legal system. Accused of committing a robbery, Gideon was too poor to hire a lawyer to represent him in court. After he was found guilty and sentenced to five years in prison, Gideon took his case to the U.S. Supreme Court. In a landmark legal decision, Gideon v. Wainwright, the Supreme Court ruled that under the U.S. Constitution, state courts are required to appoint lawyers for those individuals accused of committing a crime who cannot pay for legal representation.

Gideon was born on August 30, 1910, to Charles R. and Virginia Gregory Gideon in Hannibal, Missouri. A shoemaker, Charles Gideon died the day before Clarence’s third birthday. When Clarence was five years old, his mother remarried. He later remembered, “My stepfather never could accept me or I could not accept him. My mother was very strict and my life as a child was of the strict discipline.” He described himself as someone who could not conform and “was miserable. I was never allow[ed] to do the things of an ordinary boy.”

At the age of fourteen, Gideon ran away from home. He traveled to California, but returned to Missouri after a year. When his mother learned that he was living with his uncle near Hannibal, she had him arrested. Gideon escaped from jail, but had nowhere to go in the middle of winter. He broke into a store and stole clothes to stay warm, but was later arrested and convicted of stealing. Gideon was sentenced to three years at the Missouri State Reformatory for Boys. He later said, “Of all the prisons I have been in that was the worst.” After a year, he was released on parole.

Gideon began working at a shoe factory and got married. After starting out at two dollars a day, he was assigned a job at the factory that paid twenty-five dollars a day.

When he lost his job in 1928, Gideon began committing crimes. He was found guilty of robbery, burglary, and larceny and sentenced to ten years in the Missouri State Penitentiary. He and his wife divorced. After three years and four months in prison, he was paroled in January 1932. The country had changed, however, since Gideon had last been a free man. The Great Depression had begun, and jobs were hard to find. Gideon had little education and no work experience other than at the shoe factory. He struggled to make a living and eventually began committing crimes again. Over the next several years, Gideon was in and out of prisons across the country and suffered a number of failed marriages.

Once out of prison, Gideon saved enough money to buy a pool hall, but the business was a failure. He moved to Florida and began hanging out at the Bay Harbor Bar and Pool Hall in Panama City. In 1961, Gideon was accused of breaking into the pool hall. When he appeared in court, he was unable to pay an attorney to represent him, so he asked the judge to appoint one for him. The judge, following Florida state law, told Gideon that only defendants who had been charged with a capital offense, like murder, had the right to an attorney.

Gideon had to defend himself in court, but without an education, legal experience, or any knowledge of the law, he did not do a good job. An attorney who did not represent Gideon later said that the trial “was a simple case with a simple man, trying to act like a lawyer, but making a pitiful effort. A lawyer—not a great lawyer, just an ordinary, competent lawyer—could have made ashes of the case.” Gideon was found guilty and sentenced to five years in prison.

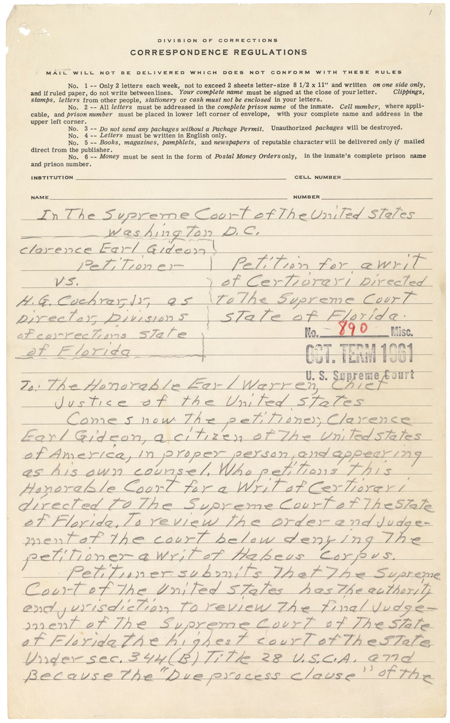

Gideon refused to give up, however, and began to research the law. Believing that he had been denied his constitutional right to legal representation, he petitioned the Florida Supreme Court to have his sentence overturned, but the court denied his petition.

He then turned to the highest court in the United States for help. Gideon filed his case in forma pauperis with the U.S. Supreme Court. In forma pauperis is Latin for “in the character or manner of a pauper.” It allows people who are too poor to afford a lawsuit or an attorney to pursue legal action without having to pay many of the legal fees and costs. He argued that his right to legal representation as guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution had been violated. From his prison cell Gideon wrote, “It makes no difference how old I am or what color I am or what church I belong to if any. The question is I did not get a fair trial. The question is very simple. I requested the court to appoint me an attorney and the court refused.”

The U.S. Supreme Court agreed to hear his case and assigned a lawyer named Abe Fortas to represent him. Fortas would go on to become a member of the U.S. Supreme Court. He argued on Gideon’s behalf that all individuals accused of committing a felony should receive legal representation.

On March 18, 1963, all nine members of the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of Gideon, stating in part, “Lawyers in criminal courts are necessities, not luxuries.” As a result, Gideon did not go free, but he did receive a new trial with legal representation and was acquitted of robbing the pool hall.

Because of Gideon’s efforts, thousands of individuals who had been tried and convicted without legal representation were granted new trials or released from Florida prisons. Over time, the right to legal representation for impoverished individuals has been extended to include juvenile offenders and adults who commit misdemeanors.

When Clarence Earl Gideon picked up a pencil to write his petition to the U.S. Supreme Court, he set a series of events in motion that changed the nation’s legal system, proving that sometimes one person can make an important difference.

Clarence Earl Gideon died of cancer on January 18, 1972, in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. He is buried in Mt. Olivet Cemetery in Hannibal, Missouri.

Text and research by Kimberly Harper

References and Resources

For more information about Clarence Earl Gideon’s life and career, see the following resources:

Society Resources

The following is a selected list of books, articles, and manuscripts about Clarence Earl Gideon in the research centers of The State Historical Society of Missouri. The Society’s call numbers follow the citations in brackets.

Manuscript Collection

- Dalton, John M. (1900-1972), Papers, 1921-1965 (C2417)

The papers of a former governor of Missouri contains a reference to Gideon v. Wainwright in folder 3350.

Outside Resources

These links, which open in another window, will take you outside the Society’s website. The Society is not responsible for the content of the following websites:

- Gideon v. Wainwright

This website created by the Oyez Project at IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law features audio recordings and transcripts of the oral arguments for Gideon v. Wainwright. - Lewis, Anthony. Gideon’s Trumpet. New York: Random House, 1964.

- PBS: The Supreme Court

This website contains a summary of Gideon v. Wainwright and features information about other important U.S. Supreme Court cases. - Urofsky, Melvin I. 100 Americans Making Constitutional History: A Biographical History. Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2004.