Henry Kirklin

Henry Kirklin was a formerly enslaved individual who became a prize-winning gardener and horticulturalist. He may have been the first African American to teach at the University of Missouri, but he did so in an informal, unofficial capacity, as the university did not allow African Americans to hold official teaching positions during his lifetime.

Kirklin was born into slavery in Boone County, Missouri, on June 6, 1858, to his enslaved mother, Jane. When he was five years old, his mother “fetched” him “out of slavery.” As a teenager, Kirklin began working at Joseph B. Douglass’s nursery and greenhouse business in Columbia. The first year he worked for Douglass he earned “30 cents a day, the second year 40 cents a day, and so on,” until after six years Kirklin earned “a dollar a day.”

After working at the nursery for several years, Kirklin joined the University of Missouri’s horticulture department as a gardener and greenhouse supervisor, perhaps at the urging of Douglass, who served as the department’s general agent. Kirklin’s knowledge and skill was quickly recognized by Samuel Mills Tracy, the head of the department. Tracy gave classroom lectures but was too busy to teach the practical, hands-on portion of his classes. Instead, he asked Kirklin to teach his students how to graft, prune, and propagate plants and trees. Because of racial segregation, which is the practice of separating people by race, Kirklin was not allowed to teach in a classroom, but instead taught outside in the open air.

It was reported that “hundreds of students learned the fine art of pruning and grafting” from Kirklin. He occasionally remarked he was “the only negro who ever taught in the University of Missouri.” In a 1913 article about Kirklin, William L. Nelson, assistant secretary of the Missouri Board of Agriculture, observed that Kirklin had been “pretty near a teacher, even if his name was not in the faculty directory.”

On May 8, 1880, Henry Kirklin married Martha “Mattie” Moss in Columbia. The couple had two daughters, Estella and Mattie, and later raised two nieces, Marjorie and Ada Powers. In 1883 Kirklin purchased half an acre of land on the outskirts of Columbia and started a commercial fruit and vegetable farm. He became a familiar sight as he sold strawberries and other produce from a wheelbarrow he pushed around town.

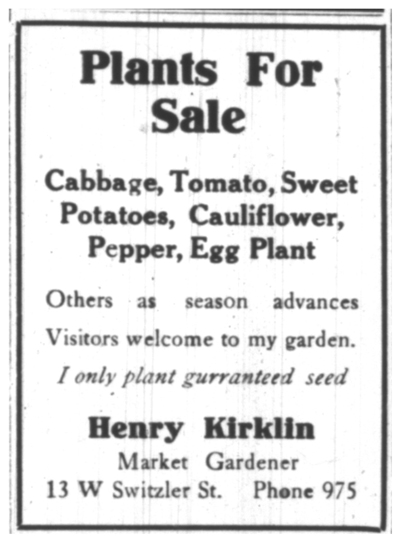

By 1900 Kirklin was so successful that he purchased additional land to keep up with the demand for his fruits and vegetables. He grew celery, lettuce, cabbage, melons, sweet potatoes, onions, beets, cucumbers, radishes, peppers, cauliflower, and tomatoes. Customers could buy food from him or purchase plants to start their own garden. Local businesses bought large amounts of his produce. University of Missouri professors brought their students to Kirklin’s farm to study “propagation of berry vines, fruit trees, and vegetables of all kinds.”

Kirklin observed which varieties of fruits and vegetables were the most successful and used them in his garden. He saved their seeds and selected only the best to start the next year’s crop. During the winter, Kirklin studied seed catalogs and read books on gardening to stay up to date on the newest methods.

While on a trip to the East Coast, he noticed the widespread use of overhead spray irrigation. Upon returning to Columbia, Kirklin built his own overhead irrigation system. Instead of paying a fee to use the city’s water, he created a small artificial pond to collect rainwater, and then used it to water his garden at no cost.

For his efforts, Kirklin won many prizes over the years. One of his most impressive accomplishments came in 1907 when he won a gold medal for his canned vegetable entry at the Jamestown Exposition fair in Virginia. In 1913, Kirklin spoke at the National Negro Business League meeting in Philadelphia, where he also answered questions from Booker T. Washington, prominent African American educator and leader. Despite his success, Kirklin freely shared his expertise with others.

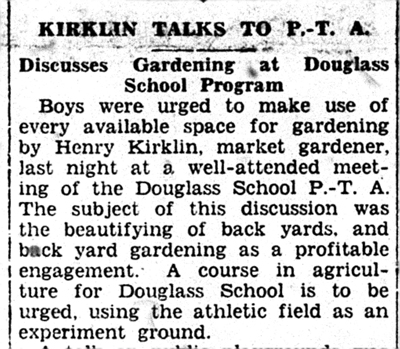

Kirklin taught at the Bartlett Agricultural and Industrial School, later known as the Dalton Institute, in Chariton County, Missouri. The school, founded by educator Nathaniel C. Bruce, provided vocational and agricultural training for African American students. Kirklin also lectured and demonstrated horticultural techniques at county fairs and in African American schools on behalf of the Missouri State Board of Agriculture. He reportedly turned down repeated offers to teach agriculture at Lincoln Institute, now Lincoln University, in Jefferson City, choosing to remain a modest “gardener.”

Kirklin was generous with not only his knowledge but also his time. An active member of the Columbia community, he attended St. Paul A.M.E. Church and was a member of St. Paul Lodge No. 12, an African American Masonic lodge. During World War I, Kirklin collected money during bond drives to support the war effort. He also reportedly helped young African Americans attend college.

Henry Kirklin died of heart disease on August 14, 1938, in Columbia. He is buried in Columbia Cemetery. As William L. Nelson had written years before Kirklin’s death, “While denied the privilege of much book learning Henry Kirklin is yet an educated man. The school in which he was educated gives no diplomas, but its course is thorough and the work exacting.”

Through his many accomplishments, Kirklin showed that despite being born enslaved and having no formal education, one could still become successful through hard work and a passion for learning and teaching.

Text and research by Kimberly Harper with research assistance by Erika Van Vranken

References and Resources

For more information about Henry Kirklin’s life and career, see the following resources:

Society Resources

The following is a selected list of books, articles, and manuscripts about Henry Kirklin in the research centers of The State Historical Society of Missouri. The Society’s call numbers follow the citations in brackets.

Articles from the Newspaper Collection

- “An Acre of Ripe Strawberries Soon.” Columbia University Missourian. May 17, 1912. p. 4. [Reel # 8820]

- “Buy Another Bond, Loan Workers Urge.” Columbia Evening Missourian. October 2, 1918. p. 1. [Reel # 7580]

- “Call Him America’s Best Negro Farmer.” Columbia Evening Missourian. October 29, 1919. p. 3. [Reel # 7582]

- “Kirklin Got Gold Medal.” Columbia Missouri Herald. November 15, 1907. p. 1. [Reel # 7510]

- “Members of the Liberty Bond Army.” Columbia Evening Missourian. October 3, 1918. p. 2. [Reel # 7580]

- “Mr. Henry Kirklin.” Columbia Professional World. December 25, 1903. p. 6. [Reel # 8114]

- “Negro Gardener’s Burial Tomorrow.” Columbia Missourian. August 16, 1938. p. 1. [Reel # 7630]

- “Negroes Hold a Fair.” Cape County Herald. November 22, 1912. p. 1. [Reel # 4137]

- “Negro Taught the Whites: Henry Kirklin Once an Instructor in Missouri’s University.” Kansas City Star. January 12, 1908. p. 17. [Reel # 20297]

- “S.F. Conley to Head Loan Drive Workers.” Columbia Evening Missourian. September 26, 1918. p. 1. [Reel # 7580]

- “‘Uncle Henry’ Kirklin Died Here Last Night.” Columbia Daily Tribune. August 15, 1938. p. 1. [Reel # 8208]

Books and Articles

- Fischer, Ernest. “Kirklin–Black and Honest.” The Missouri Ruralist. v. 65, no. 20 (April 15, 1924), p. 13. [REF F560 M6915m MICRO]

- Mather, Frank Lincoln, ed. Who’s Who of the Colored Race. v. 1. Chicago: Frank Mather, 1915. [REF Vertical File: Horticulture–Missouri]

- Boone County, Missouri, Black Archives, Collection (C4057)

The Boone County Black Archives Collection is an artificial collection documenting the lives of blacks living in Boone County, Missouri. The items include photographs, memoirs, scrapbooks, correspondence, news clippings, and other ephemera. Folders 11 and 23 contain a photograph and information about Henry Kirklin. - Missouri, Columbia, Social and Economic Census of the Colored Population, 1901 (C1082)

Family reports listing name, age, occupation, weekly earnings and color of husband, wife, children, married children at home, and others living with the family. Reverse side lists date and/or age at marriage, deaths within the year, property owned, amount owed, housing and sanitary conditions, education, family expenditures, and previous residence. Most questions were answered in full. The records are arranged alphabetically by family name. Henry Kirklin is referenced in this collection.

Outside Resources

- Cook, Delia Crutchfield. “Shadow Across the Columns: The Bittersweet Legacy of African Americans at the University of Missouri.” PhD diss. University of Missouri, 1996.

- Nelson, W. L. “Henry Kirklin, Gardener.” The Country Gentleman. v. 78, part 2 (1913), p. 1495.

- Rosa, Jr., J. T. “Making Money on a Two-Acre Farm.” Market Growers Journal. v. 28, no. 8 (April 15, 1921), p. 9.