Rose O'Neill

Introduction

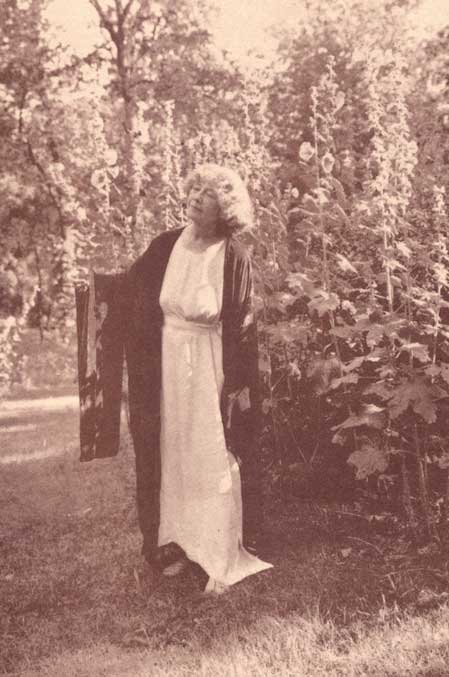

Rose O’Neill was a self-trained artist who periodically lived in the Missouri Ozarks throughout her adult life. She built a successful career as a magazine and book illustrator and, at a young age, became the best-known and highest-paid female commercial illustrator in the United States. She also wrote novels and poetry. O’Neill earned a fortune and international fame by creating the Kewpie, the most widely known cartoon character until Mickey Mouse.

Early Years

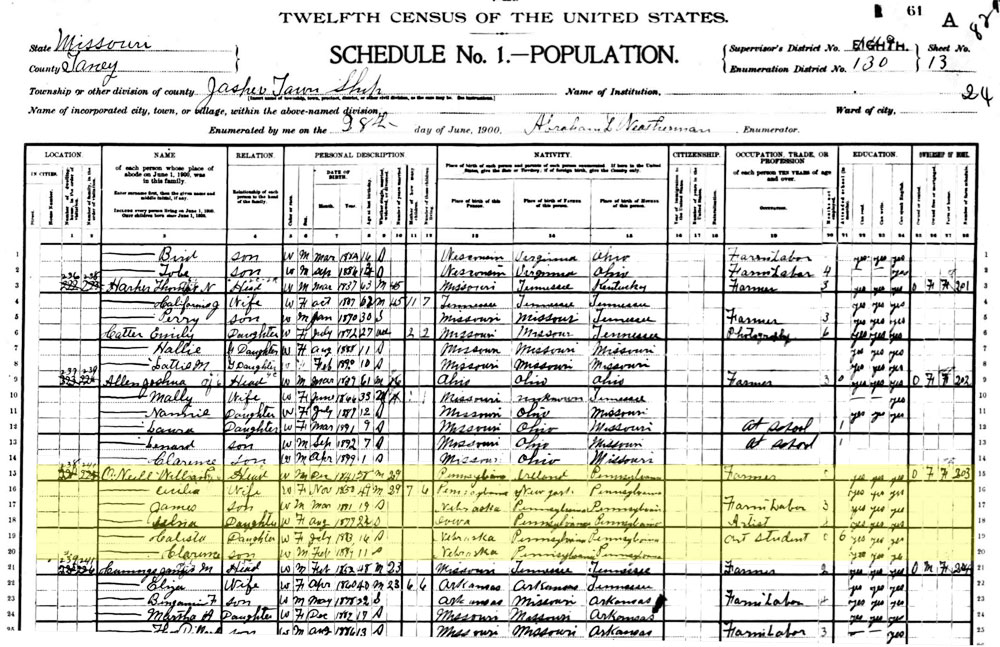

Rose Cecil O’Neill was born on June 25, 1874, in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. Her parents were William Patrick Henry and Alice Cecilia Asenath Senia Smith O’Neill. She had two sisters—Lee and Callista—and three brothers—Hugh, James, and Clarence. O’Neill’s father was a bookseller of Irish descent who loved literature, art, and theatre. Her mother was a gifted musician, actress, and teacher. As a young girl, O’Neill traveled with her family in a Conestoga wagon to rural Nebraska. There she grew up in a loving family that actively supported each member’s artistic and intellectual interests.

O'Neill Family

Rose’s family members and their life dates are as follows:

- William Patrick (1841–1936)

- Alice Aseneth Cecelia Smith (1850–1937)

- John Hugh (1872–1956)

- Rose Cecil (1874–1944)

- Mary Ilena (Lee) (1877–1967)

- James (1881–1905)

- Callista (1883–1946)

- Edward (1886–1888)

- Clarence Gerald (1889–1961)

James, Callista and Edward probably had more than one given name each. James died at Bonniebrook, as did Meemie and Callista. Most are buried there; O’Neill’s father is in a military cemetery in California, Edward is buried in Nebraska, and Clarence in Nevada, MO.

Rose O’Neill revealed her talents as a writer and artist at a young age. She won a drawing contest for the Omaha World-Herald when she was thirteen. At age nineteen, O’Neill traveled alone to New York City to sell her first novel. She brought with her a portfolio of sixty illustrations and sketches and showed them to various New York magazine editors and publishers. Editors admired her artwork and gave her commissions for illustrations and commercial posters. O’Neill’s career as a professional artist had begun.

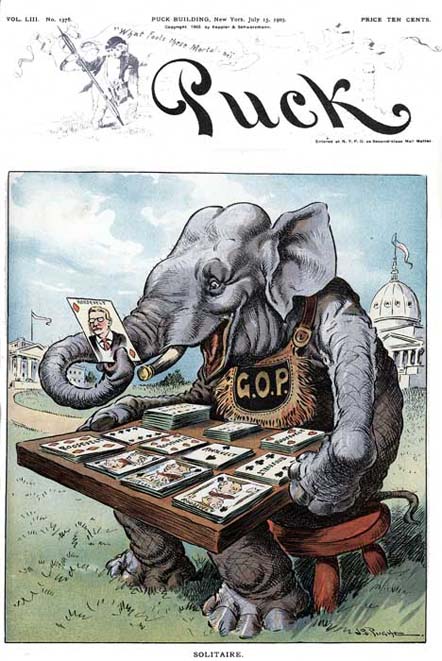

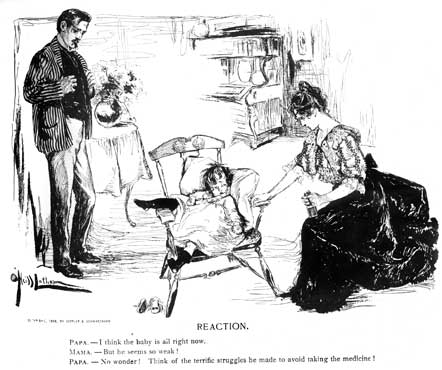

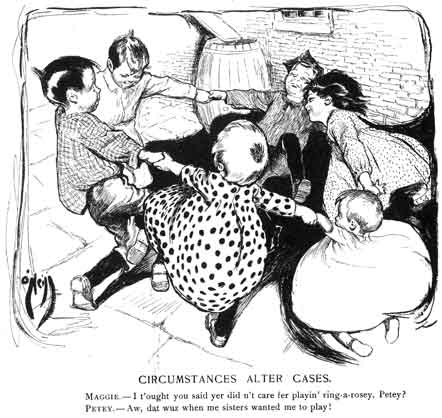

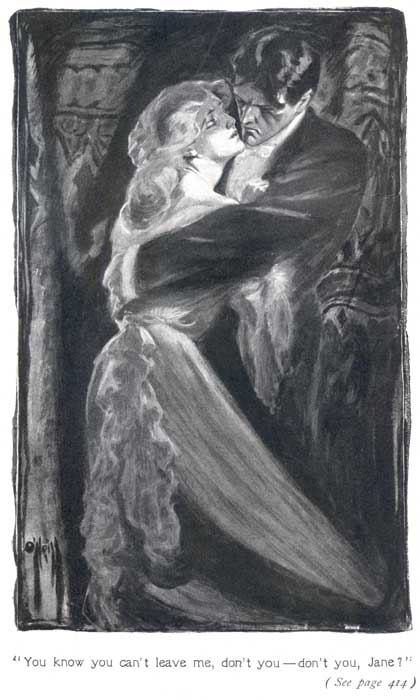

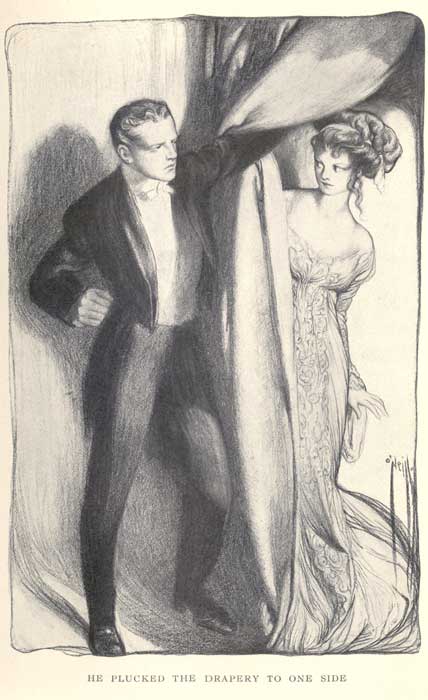

By her early twenties, O’Neill was nationally known for her illustrations in popular magazines such as Ladies Home Journal, Good Housekeeping, and Woman’s Home Companion. She also drew hundreds of cartoons for the humorous magazine Puck. During this period of her life O’Neill had two brief marriages, the first to Gray Latham in 1896 and then to Harry Leon Wilson in 1902. She remained single after 1907.

Bonniebrook

While O’Neill worked as an artist in New York City, her family moved from Nebraska to a homestead in Taney County, Missouri. When she visited her family for the first time in Missouri, O’Neill fell in love with the enchanting Ozark mountains, woods, and streams. She named their charming farmstead “Bonniebrook” and returned to it throughout her working career. Near the end of her life, O’Neill retired there.

Bonniebrook was a rambling, three-story, fourteen-room structure completed around 1910 by Rose O’Neill’s father, brothers, and local craftsmen. It stood in a remote and rustic setting on Bear Creek in Taney County until it was destroyed by fire in 1947. In 1993 a replica house was completed by the Bonniebrook Historical Society, and the homestead acreage is now on the National Register of Historic Places.

Bonniebrook and the surrounding Ozark woods became a source of artistic inspiration for O’Neill. At Bonniebrook, surrounded by her loving family, Rose O’Neill first dreamed of and created the cute, good-natured characters that would make her world famous.

Kewpies

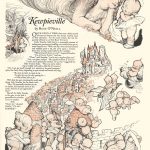

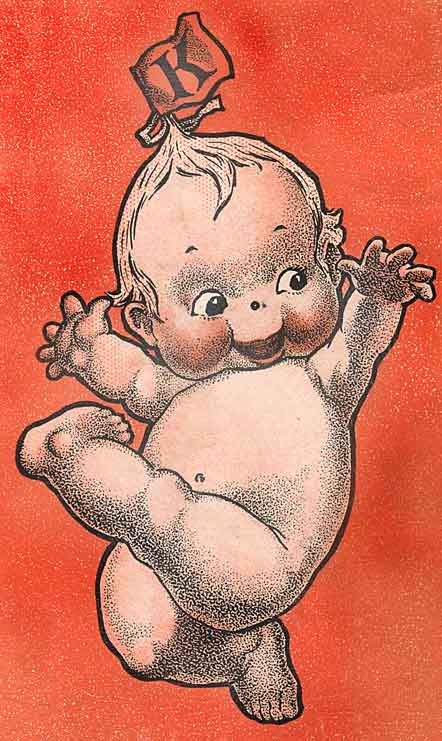

O’Neill’s Kewpies made their first appearance as character drawings in a women’s magazine in December 1909. Kewpies were fanciful, elf-like babies with a top-knot head, a wide smile, and sidelong eyes. They were both impish and kind and solved all kinds of problems in humorous ways. O’Neill described them as “a sort of little round fairy whose one idea is to teach people to be merry and kind at the same time.” The Kewpies were immediately popular with both children and adults.

In 1913 O’Neill patented a doll based on the Kewpie character. She oversaw the making of the first Kewpie dolls originally produced in Germany. The dolls were sold all over the world along with a vast array of Kewpie merchandise such as tableware, fabrics, and trinkets.

Female Illustrator and Artist

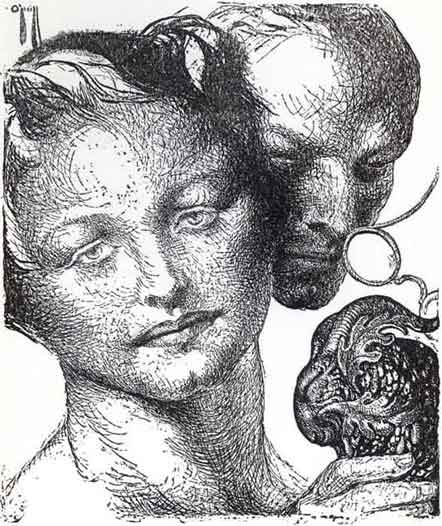

By 1914 O’Neill was the highest-paid female illustrator in America. Her income allowed her to support her family in Missouri and travel extensively in Europe. There she easily made friends with fellow artists and writers and hosted expensive parties. In this lively environment, O’Neill produced her serious art, much of which she labeled her “Sweet Monster” art. Influenced by European artists and her own Irish-American upbringing, O’Neill merged mythic-like figures with animal traits and pushed them into extreme and unusual poses in her paintings and sculptures.

Her fine art exhibits, in both Paris and New York, revealed a much different side to her artistic personality. O’Neill’s strange, intertwining shapes—twirling amid a whirlwind of decorative elements—created a kind of fantastical art that both enthralled and challenged her admirers.

Writer and Suffragist

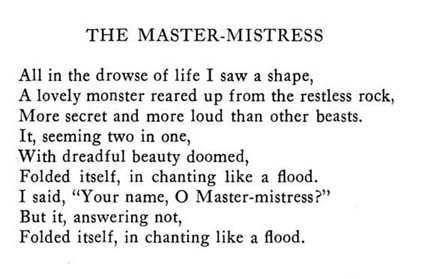

In addition to her illustrations in magazines, books, and newspapers, Rose O’Neill also wrote children’s books featuring the Kewpies, as well as novels and poetry . O’Neill explored the creative process and the complex relationship between women and men in her novels and poems. Despite her success as an artist and writer, O’Neill could not vote in public elections because she was a woman. O’Neill worked diligently, along with her sister Callista, to support the suffragist movement. She drew posters and cartoons and marched in protest parades. Her efforts helped women gain the right to vote in 1920.

O'Neill’s Legacy

O’Neill worked industriously and financially supported her family and many fellow artists throughout her career. In the 1930s, her fortunes dwindled due to her generosity and the financial stress of a worldwide economic depression. Also, after thirty years of popularity, interest in the Kewpie character started to wane. O’Neill’s artwork—and the Kewpies—were no longer in high demand as realistic photographs replaced fanciful illustrations in magazines and newspapers.

In 1937 O’Neill retreated permanently to Missouri to live at Bonniebrook. There she wrote her memoirs with the help of her friend, the Ozark folklorist Vance Randolph. Her autobiography, published many years after her death, reveals her personal philosophy: “Do good deeds in a funny way. The world needs to laugh or at least smile more than it does.” She died on April 6, 1944, at the age of 69. She was buried at Bonniebrook.

Text and research by Carlynn Trout

References and Resources

For more information about Rose O’Neill’s life and career, see the following resources:

Society Resources

The following is a selected list of books, articles, and manuscripts about Rose O’Neill in the research centers of The State Historical Society of Missouri. The Society’s call numbers follow the citations in brackets.

Articles from the Missouri Historical Review

- Brashear, Minnie M. “Missouri Verse and Verse-Writers.” v. 19, no. 1 (October 1924), pp. 64–68.

- “Missouri Women in History: Rose O’Neill.” v. 62, no. 4 (July 1968), inside back cover.

- “A Missourian’s Dolls Amused a Generation of American Children.” v. 48, no. 4 (July 1954), pp. 368–370.

Articles from the Newspaper Collection

- Garside, Frances L. “How Rose O’Neill Made Good.” Kansas City Star. February 18, 1917. p. 3C. [Reel # 20686]

- Martyn, Marguerite. “Creator of Kewpies – Rose O’Neill: Returns to Her Starting Point in Taney County, Mo.: ‘Is There to Stay.’” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. August 29, 1937. Women’s Sunday Magazine, p. 1, 3H. [Reel # 42537]

- Mecher, Louis. “Rose O’Neill Infused Her Kewpies with Spirit of a Rare Personality.” Kansas City Times. April 7, 1944. pp. 1–2C. [Reel # 24088]

- “Rose O’Neill Infused Her Kewpies with Spirit of a Rare Personality.” Kansas City Times. April 7, 1944. [Reel # 24088]

- “Rose O’Neill Is Dead.” Kansas City Star. April 6, 1944. [Reel # 20686]

- “Rose O’Neill Is Put Away by Bonniebrook’s Green Bank.” Springfield Leader and Press. April 7, 1944. p. 1. [Reel # 49067]

- “Rose O’Neill, Poet-Artist of the Ozarks.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. June 29, 1913. Sunday Supplement, p. 3. [Reel # 41993]

Books Written and Illustrated by Rose O’Neill

- Garda. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Doran & Co., 1929. [I On2ga]

- The Goblin Woman. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Doran & Co., 1930. [I On2go]

- The Kewpie Kutouts. New York: Frederick A. Stokes Co., 1914. [I J On2kk In Case]

- The Kewpies and Dotty Darling. New York: George H. Doran Co., 1912. [I J On2kd In Case]

- The Kewpies and the Runaway Baby. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Doran & Co., 1928. [I J On2kr In Case]

- The Kewpies, Their Book. New York: Frederick A. Stokes Co., 1913. [I J On2kb In Case]

- The Lady in the White Veil. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1909. [I On2la]

- The Loves of Edwy. Boston: Lothrop Publishing Co., 1904. [I On2lo]

- The Master-Mistress: Poems. New York: A. A. Knopf, 1922. [I On2m]

- Scootles and Kewpie Doll Book. Akron: Saalfield Publishing Co., 1936. [I J On2sc In Case Oversize]

- Scootles in Kewpieville. Akron: Saalfield Publishing Co., 1936. [I J On2s In Case Oversize]

- The Story of Rose O’Neill: An Autobiography. Miriam Formanek-Brunell, ed. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1997. [REF F508.1 On2on 1997]

Books Illustrated by Rose O’Neill

- Caeser, Irving. Sing a Song of Safety. New York: I. Caesar, 1937. [784.6 C116]

- Fillmore, Parker Hoysted. The Hickory Limb. New York: John Lane Co., 1910. [813 F485]

- Fillmore, Parker Hoysted. A Little Question of Ladies’ Rights. New York: John Lane Co., 1916. [813.5 F485]

- O’Neil, George. Tomorrow’s House, or The Tiny Angel. New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., 1930. [I Onlt]

- Quinn, Vernon. The Kewpie Primer. New York: F. A. Stokes Co., 1916. [I J On2kp In Case]

- Wilson, Harry Leon. The Lions of the Lord: A Tale of the Old West. Boston: Lothrop Publishing Co., 1903. [289.3 H693]

- Woman’s Home Companion. Better Babies Bureau. Our Baby’s Book. New York: Woman’s Home Companion, 1914. [I On2o]

Books and Articles about Rose O’Neill

- Armitage, Shelley. Kewpies and Beyond: The World of Rose O’Neill. Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 1994. [REF F508.1 On2ar]

- Christensen, Lawrence O., William E. Foley, Gary R. Kremer, and Kenneth H. Winn, eds. Dictionary of Missouri Biography. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1999. pp. 584-586. [REF F508 D561]

- Currie, Stephen. “Rose Cecil O’Neill and Her Kewpies.” American History. February 2005, pp. 24-26, 70-71. [REF Vertical File]

- Dains, Mary K., ed. Show Me Missouri Women: Selected Biographies. Kirksville, MO: Thomas Jefferson University Press, 1989. v. 1, pp. 131-132. [REF F508 Sh82 v.1]

- McCanse, Ralph Alan. Titans and Kewpies: The Life and Art of Rose O’Neill. New York: Vantage Press, 1968. [REF F508.1 On2m]

- Nevins, Mona, and Bob Gibbons. “Sweet Monsters”: The Serious Art of Rose O’Neill and Her 1921 Paris Exhibit. Branson, MO: Bonniebrook Historical Society, 1993. [REF F508.1 On2sw]

- Ruggles, Rowena Godding. The One Rose: Mother of the Immortal Kewpies. 2nd ed. Albany, CA: privately published, 1972. [REF F508.1 On2r 1972]

- Stepenoff, Bonnie. “Rose Cecil O’Neill.”American National Biography. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999. v. 16, pp. 733-734. [REF 920 Am37 v. 16]

Manuscript Collection

- Mrs. Walter Griffen Scrapbooks (C1402)

Newspaper and magazine clippings of pictures and articles of Missouri scenes, the Ozarks, and Hannibal. Volume 1 contains information about O’Neill. - John G. Neihardt Papers (C3716)

Folder 54 contains a letter from Rose O’Neill to the poet Neihardt. - Rose O’Neill Papers (SP0026)

The Rose O’Neill Papers consist of the personal correspondence of Rose O’Neill and her family members and friends. - Lucile Morris Upton Papers (C3869)

The personal and professional papers of a Springfield, Missouri, journalist and writer consist of newspaper clippings, correspondence, research notes, manuscripts, pamphlets, photographs, and scrapbooks. The papers are especially strong in the history of Springfield and the Ozarks region, as well as Ozark folklore. Information on Rose O’Neill can be found in folder 144.

Outside Resources

These links, which open in another window, will take you outside the Society’s website. The Society is not responsible for the content of the following websites:

- Biographical Database of NAWSA Suffragists 1890-1920

The National American Woman Suffrage Association has created an online database of biographical sketches of women involved in the suffrage movement. The website includes a biography of Rose O’Neill. - Bonniebrook Historical Society

This is the Website for the Bonniebrook Historical Society, a society dedicated to providing information about Rose O’Neill, her life in the Missouri Ozarks, and her artistic career. - Brandywine River Museum

Brandywine River Museum in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, is a museum of regional and American art. Illustrations by Rose O’Neill are included in the Brandywine collection of major American illustrators. The museum mounted an exhibit entitled The Art of Rose O’Neill in 1989. It published a catalog by the same name in which a significant essay by Helen Goodman on O’Neill’s work appears. - The Ozarkiana Collection

The Ozarkiana Collection, gathered by Townsend Godsey, a longtime Ozarks researcher and writer, is housed in Lyons Memorial Library at the College of the Ozarks at Point Lookout, Missouri. This special collection contains various pictures and writings of Rose O’Neill that were donated by her to the college before her death.