Satchel Paige

Introduction

Satchel Paige was a famous African American baseball pitcher who helped break down racial barriers in professional sports. His incredible speed, skill, and showmanship made him a national baseball hero. He pitched in the Negro Leagues before joining the major leagues in 1948. In 1971 Paige became the first player from the Negro Leagues elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Early Years and Education

Leroy “Satchel” Paige was born July 7, 1906, in Mobile, Alabama. He was the seventh child of twelve born to John and Lula Coleman Paige. Satchel’s father was a gardner and his mother worked as a domestic servant. Because John Paige was often unemployed, the family lived in poverty. In his autobiography, Paige remembered, “We played in the dirt because we didn’t have toys. We threw rocks. There wasn’t anything else to throw.”

As Satchel grew older, he helped support his family. He collected empty bottles for resale, delivered ice, and worked as a baggage porter at Mobile’s Louisville & Nashville’s rail depot.

On one occasion when Satchel was loaded down with bags, another porter told him, “You look like a walking satchel tree.” It was then, Satchel later recalled, “LeRoy Paige became no more and Satchel Paige took over.”

Satchel rarely attended school. Instead, he skipped class to play baseball and fish in Mobile Bay. Satchel soon developed a reputation as the best school-age pitcher in Mobile’s black section, but he could not stay out of trouble.

Reform School

In 1918 twelve-year-old Satchel was convicted of shoplifting and was sentenced to five years in the Alabama Reform School for Juvenile Negro Lawbreakers. Satchel attended class, worked on the school farm, joined the school choir, and became a member of the drum and bugle corps.

He honed his skills as a baseball player under the direction of Coach Edward Byrd. Coach Byrd showed Satchel how to use his physical skill and strength to become a powerful and proficient right-handed pitcher. Most importantly, Byrd taught Satchel that he could not depend on his physical talent alone—he would also have to outwit his opponents. By studying a batter’s stance, the placement of his feet, and the position of his bat, Satchel could determine the player’s weaknesses at the plate.

Satchel was paroled on December 31, 1923, with “an excellent record.” He later said, “Those five and a half years there did something for me—they made a man out of me. If I’d been left on the streets of Mobile to wander with those kids I’d been running around with, I’d of ended up as a big bum, a crook. You might say I traded five years of freedom to learn how to pitch.”

Baseball

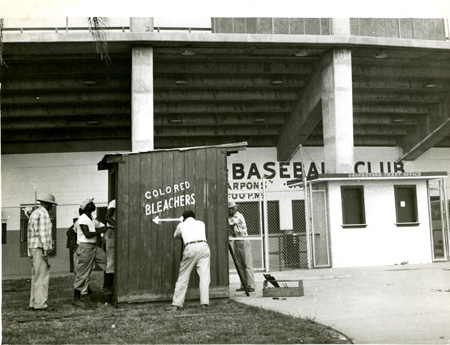

After baseball became segregated in 1889, blacks were prohibited from playing in the major leagues. In response, black baseball players formed their own semi-professional and professional baseball leagues that were collectively referred to as the “Negro Leagues.”

Paige returned home and joined the black semi-professional Mobile Tigers. It was then, he said, “I gave up kid’s baseball—baseball just for fun—and started baseball as a career.” At six foot three inches tall, the lanky right-handed pitcher quickly developed a reputation as a formidable opponent.

In 1924, playing for the Tigers, Paige won an estimated thirty games with only one loss. In 1926 he joined the professional Chattanooga Black Lookouts for two successful seasons. Paige then spent the next several years going from team to team in search of a more lucrative paycheck.

Among the Negro League teams he played for between 1927 and 1947 were the Birmingham Black Barons, Baltimore Black Sox, Cleveland Cubs, Pittsburgh Crawfords, Kansas City Monarchs, New York Black Yankees, and Memphis Red Sox.

When not playing with a team, Paige and other black players formed freelance barnstorming teams that toured the country playing other teams in exhibition games to make extra money. Paige spent long hours on the road and rarely saw his wife when barnstorming across the country. Life on the road was not easy for black players and they regularly endured racist taunts from spectators. Due to segregation, they were not allowed to stay at hotels where whites lodged or dine at restaurants used by whites. Paige refused to play in towns where he could not get a hotel room or a meal.

Despite the prevailing racism of the era, Paige attracted white spectators with his dazzling pitching skills. He could throw a variety of pitches with accuracy and speed that few could match. He gave his pitches colorful names such as “jump ball, bee ball, screw ball, woobly ball, whipsy-dipsy-do, a hurry-up ball, a nothin’ ball, and a bat dodger.”

Paige used his arsenal of different pitches to confuse batters. He might sidearm the ball across the plate, follow with a fastball, and then throw his signature “hesitation pitch” in which he would hesitate during his wind-up, often messing up the batter’s timing.

In 1938, while playing baseball in Mexico, Paige injured his pitching arm. At the age of thirty-two, he feared his career was over. J.L. Wilkinson, owner of the Kansas City Monarchs, signed Paige to play first base for his second-string team, the Kansas City Travelers. Although many believed his days on the pitcher’s mound were finished, Paige miraculously recovered the following year, and joined the Kansas City Monarchs.

Family Life

On October 26, 1934, Paige married Janet Howard. He married Lucy “Luz” Maria Figueroa in 1940 while playing ball in Puerto Rico. Because he had not divorced his first wife, Paige’s marriage to Figueroa was not legal. He divorced his first wife in 1943. Paige later married Lahoma Brown and together the couple had seven children.

The Rookie

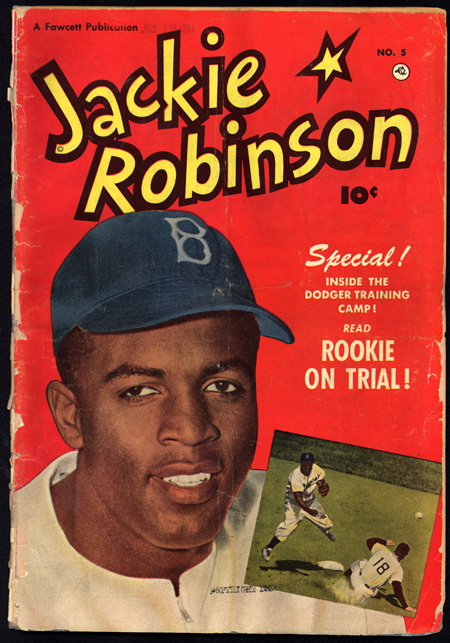

In 1947, Jackie Robinson became the first African American to play major league baseball in the twentieth century. In his autobiography, Paige declared, “I’d been the guy who’d started all that big talk about letting us in the big time. I’d been the one who’d opened up the major league parks to colored teams. I’d been the one who the white boys wanted to barnstorm against…It still was me that ought to have been first.” Paige, at age forty-one, was viewed by many to be too old to play in the major leagues.

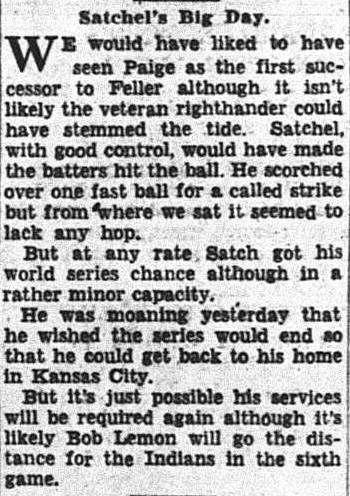

One year after Jackie Robinson joined the Brooklyn Dodgers, Paige signed with the Cleveland Indians. At forty-two years old, he was the oldest rookie to play in the major leagues. Paige’s pitching helped the Cleveland Indians beat the Boston Braves to win the 1948 World Series. He was the first African American athlete to play in a World Series.

The National Baseball Hall of Fame

Paige stayed with the Indians for one more season and then played for the St. Louis Browns for three years. He played his final season in the major leagues in 1965 with the Kansas City Athletics. In order to qualify for his Major League Baseball pension, Paige briefly joined the Atlanta Braves in 1968 as a pitching coach.

In 1971 Paige became the first player from the Negro Leagues elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York.

Death and Legacy

LeRoy “Satchel” Paige died of a heart attack on June 8, 1982, in Kansas City, Missouri. He is buried in Forest Hill Memorial Park Cemetery in Kansas City, Missouri.

Because much of his forty-three year career was spent in the Negro Leagues where record keeping was spotty, it is difficult to document Satchel Paige’s lifetime career statistics. It is clear, however, that Paige won the respect of his peers—both white and black—during his time in baseball. Today he is widely recognized as one of the greatest pitchers in baseball history.

Legendary Boston Red Sox slugger Ted Williams claimed, “Paige was the greatest pitcher in baseball.” Famed New York Yankee Joe DiMaggio said Satchel Paige was the “best and fastest pitcher I’ve ever faced.” Celebrated St. Louis Cardinal pitcher Dizzy Dean remarked, “He’s a better pitcher than I ever hope to be.” Homestead Grays first baseman and Hall of Famer Buck Leonard declared, “He threw fire.”

Paige’s showmanship, athleticism, and personality attracted both white and black audiences. He proved that black athletes could compete with and beat their white counterparts, helping pave the way for fellow African Americans to join Major League Baseball.

Text and research by Kimberly Harper

References and Resources

For more information about Satchel Paige’s life and career, see the following resources:

Society Resources

The following is a selected list of books, articles, and manuscripts about Satchel Paige in the research centers of The State Historical Society of Missouri. The Society’s call numbers follow the citations in brackets.

Articles from the Newspaper Collection

- “A Giant is Returned to Earth.” Kansas City Star. June 13, 1982. pp. A1, A18. [Reel # 22250]

- “The Life and Times of Satchel Paige.” Kansas City Times. June 9, 1982. pp. D1-2. [Reel # 22250]

- “We Lost Satchel.” Kansas City Star. June 9, 1982. pp. A1, A12. [Reel # 22250]

Books and Articles

- Bruce, Janet. The Kansas City Monarchs: Champions of Black Baseball. Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1985. [REF H128.131 B83]

- Christensen, Lawrence O., William E. Foley, Gary R. Kremer, and Kenneth H. Winn, eds. Dictionary of Missouri Biography. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1999. pp. 591-593. [REF F508 D561]

- Heapy, Leslie A., ed. Satchel Paige and Company: Essays on the Kansas City Monarchs, Their Greatest Star, and the Negro Leagues. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2007. [REF F508.1 P152he]

- Holway, John B. Josh and Satch: The Life and Times of Josh Gibson and Satchel Paige. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 1992.[REF F508.1 P152ho 1992]

- Paige, Satchel. Maybe I’ll Pitch Forever. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1993. [REF F508.1 P 152 1993]

- Shirley, David. Satchel Paige. New York: Chelsea House, 1993. [REF F508.1 P152sh]

- Spivey, Donald. “If You Were Only White”: The Life of Leroy “Satchel” Paige. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2012. [REF F508.1 P152sp]

- Tye, Larry. Satchel: The Life and Times of an American Legend. New York: Random House, 2009. [REF F508.1 P152t]

Manuscript Collection

- Kansas City Monarchs Oral History Collection, 1978-1981 (K0047)

The Kansas City Monarchs baseball team was a charter member of the Negro National League which was established in 1920. The Monarchs were active from 1920 until the integration of baseball in the 1950’s. In 1978 Janet Bruce and Catherine T. Rocha applied for and received a grant from the Friends of the Library at the University of Missouri-Kansas City to conduct a series of oral history interviews with surviving members of the Kansas City Monarchs.In addition to the oral history interviews on cassette tapes, the collection includes correspondence and reports related to grants which Janet Bruce and Catherine T. Rocha held while gathering their eighteen interviews with persons who played with or were associated with the Kansas City Monarchs.

Outside Resources

These links, which open in another window, will take you outside the Society’s website. The Society is not responsible for the content of the following websites:

- National Baseball Hall of Fame

This website provides information about Satchel Paige’s career statistics and his induction speech to the National Baseball Hall of Fame.