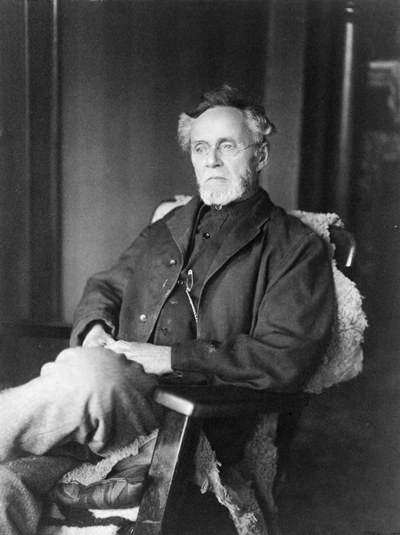

A. T. Still

Introduction

A. T. Still was the father of osteopathic medicine. As a physician, Still became dissatisfied with traditional medicine and sought to treat patients using an alternative method that he called osteopathy. Osteopathy seeks to treat a patient’s illness through the adjustment and manipulation of a patient’s musculoskeletal system. Widely thought to be a fraud when he began teaching osteopathy, Still established a form of alternative medicine now practiced throughout the world.

Early Years and Education

Andrew Taylor Still was born on August 6, 1828, in Lee County, Virginia, to the Reverend Abram and Martha Moore Still. Abram was a Methodist circuit rider, a preacher assigned to serve a specific geographic area who often traveled long distances on horseback between churches since there were not enough preachers for every individual church. This meant Abram was often away from home for long periods. He also served as a physician, tending to the sick.

Abram Still’s career as a circuit rider required the family to move frequently. After the Still family moved to Bloomington in Macon County, Missouri, in 1837, Andrew’s education was sporadic and split between attending school and being taught by his parents. He worked on the family farm and spent his free time roaming through the country and hunting.

Split over Slavery

Not long after the Stills settled in Missouri, the issue of slavery split the Methodist Episcopal Church. When the church was founded in 1784, it opposed slavery. Over time, the growing influence of enslavers from the south and disagreements over the issue created a division within the church.

In 1844 the Methodist Episcopal Church, South was formed. Methodist preachers, including Abram Still, were forced to choose between the Methodist Episcopal Church and the new Methodist Episcopal Church, South. A staunch abolitionist, Abram Still was one of only fourteen Missouri Methodist preachers who chose to stay in the original church, while eighty-six joined the new church sympathetic to slavery.

"Bleeding Kansas"

On January 24, 1849, A. T. Still married Mary M. Vaughn, and later that year their first child was born. When his parents were transferred by the Methodist church to the Wakarusa Shawnee Indian Mission in eastern Kansas, Still and his family followed them. He farmed and helped his father provide medical care to the Shawnee.

Life at the mission, however, was upended by the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. The act created the states of Kansas and Nebraska and opened new land for settlement. It also permitted voters in the new states to decide if slavery would be allowed or not. Pro-slavery southerners, including many Missourians, wanted to see Kansas become a slave state. Numerous pro-slavery settlers moved to Kansas in anticipation of voting in favor of slavery. Violence erupted between anti-slavery Free-Staters and pro-slavery Border Ruffians, leading to the nickname “Bleeding Kansas.”

The Civil War

Like his father, Still did not believe in slavery. He joined the anti-slavery Free-Staters and served in the Kansas territorial legislature. The 1850s brought heartbreak for Still. In 1855 his infant son George died, and four years later his wife, Mary, died shortly after giving birth to the couple’s fifth child, Lorenzo, who also died. Widowed with three young children, Still married a second time, to Mary Elvira Turner on November 25, 1860. The coming of the Civil War distracted Still from the many personal losses he had suffered.

On September 6, 1861, Still enlisted in the Ninth Kansas Cavalry (US) and served as a hospital steward until he was discharged in 1862. He later served in the Eighteenth and Twenty-First Kansas Militia regiments. In early 1864 two of Still’s own children, as well as a child he had adopted, died from meningitis. A fourth child died of pneumonia.

The experience of losing his children in spite of medical care left Still heartbroken. Many of the drugs that doctors prescribed at that time, such as arsenic and mercury, were harmful. Unfortunately, doctors did not know that the medicines they used were toxic because pharmacology was not very advanced. Common medical practices such as purging, vomiting, blistering, and bleeding often left patients in a weakened condition or led to their deaths. Troubled by the death of his children, Still began to doubt traditional medicine and the use of medical drugs.

Osteopathy

After the war ended, Still returned home but was unable to farm due to a hernia he suffered during the Civil War battle of Westport, Missouri. Despite his doubts about traditional medicine, he worked as a physician to provide for his family.

Still stopped treating his patients with medicinal drugs and began to study alternative theories such as magnetism, mesmerism, phrenology, and spiritualism. He became interested in the human skeleton and dug up Native American graves to obtain bodies for study. Still came to believe that a properly aligned musculoskeletal system would lead to good health, while an out-of-alignment system would result in poor health. Bones, muscles, and joints could be manipulated and adjusted by a physician to improve a patient’s health without the use of drugs. He called his theory of medicine “osteopathy,” a name taken from the Greek words meaning “bone” and “suffering.”

Still’s beliefs were radical for their time, and he was called crazy and eccentric by many people. The Methodist Church expelled him and his own family shunned him. Still traveled from town to town, hoping to attract new patients. Mary Still sold magazine subscriptions to supplement her husband’s meager earnings. Unwelcome in Kansas, Still returned to Missouri.

American School of Osteopathy

In 1875 Still and his family moved to Kirksville, Missouri, where he advertised himself as a “Lightning Bone Setter.” Upon seeing someone who was sick or crippled, Still often treated them for free, hoping to draw attention to his medical practice. Word began to spread about the doctor who treated patients with his hands and not with drugs. In time, he attracted a large number of patients, contributing to Kirksville’s growth.

On November 1, 1892, Still opened the American School of Osteopathy (ASO), now called A. T. Still University, and began teaching osteopathy. Unlike many medical schools at the time, he permitted both women and African Americans to enroll in classes.

Over the next few decades, the school grew at a rapid rate as dozens of students completed the program and became doctors of osteopathy, opening their own offices across the country. Still’s dream of an alternative to traditional medicine had come true.

Death and Legacy

After enjoying years of teaching osteopathy to hundreds of students, Still suffered a severe stroke in 1914 and lost his ability to speak. He died on December 12, 1917, and is buried in Forest-Llewellyn Cemetery in Kirksville, Missouri.

Since A. T. Still’s death, osteopathy has continued to thrive. Today there are thousands of osteopaths practicing around the world, evidence that pursuing one’s beliefs can change countless lives.

In honor of his contributions to society, a bronze bust of Andrew Taylor Still is enshrined in the Hall of Missourians at the Missouri State Capitol.

Text and research by Kimberly Harper

References and Resources

For more information about Andrew Taylor Still’s life and career, see the following resources:

Society Resources

The following is a selected list of books, articles, and manuscripts about Andrew Taylor Still in the research centers of The State Historical Society of Missouri. The Society’s call numbers follow the citations in brackets.

Articles from the Missouri Historical Review

- Hulburt, Ray G. “A. T. Still, Founder of Osteopathy.” v. 19, no. 1 (October 1924), pp. 25-35.

Articles from the Newspaper Collection

- “Dr. A. T. Still, Founder of Osteopathy, Died Yesterday.” Kirksville Journal. December 13, 1917. p. 1. [Reel # 25194]

- “Dr. A. T. Still, Founder of Osteopathy, Dies Early Today.” Kirksville Daily Express. December 12, 1917. p. 1. [Reel # 24858]

Books and Articles

- Christensen, Lawrence O., William E. Foley, Gary R. Kremer, and Kenneth H. Winn, eds. Dictionary of Missouri Biography. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1999. pp. 721-723. [REF F508 D561]

- Still, Andrew T. Autobiography of Andrew T. Still: With a History of the Discovery and Development of the Science of Osteopathy. Indianapolis: American Academy of Osteopathy, 2000. [REF 508.1 St54 2000]

- Still, Charles E., Jr. Frontier Doctor, Medical Pioneer: The Life and Times of A. T. Still and His Family. Kirksville, MO: Thomas Jefferson University Press, 1991. [REF F508.1 St54st]

- Trowbridge, Carol. Andrew Taylor Still: 1828-1917. Kirksville, MO: Thomas Jefferson University Press, 1991. [REF F508.1 St54t]

Outside Resources

- A. T. Still University Museum of Osteopathic Medicine

The papers of Andrew Taylor Still are held at the A. T. Still University Museum of Osteopathic Medicine in Kirksville, Missouri.