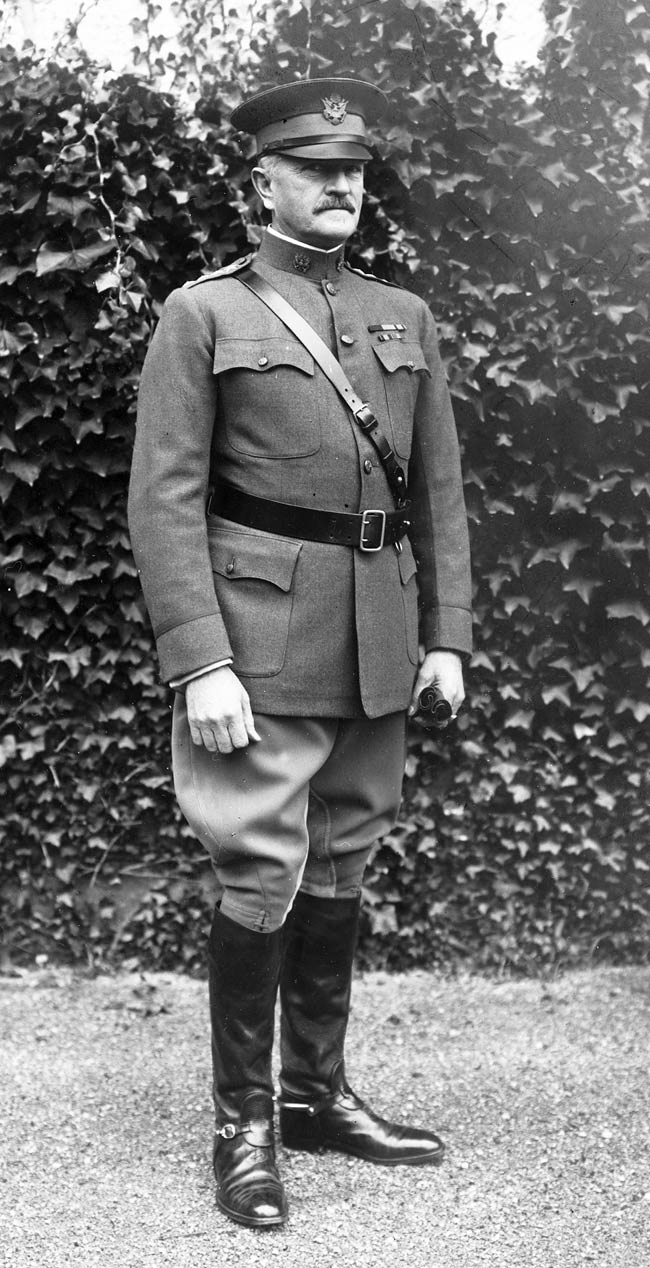

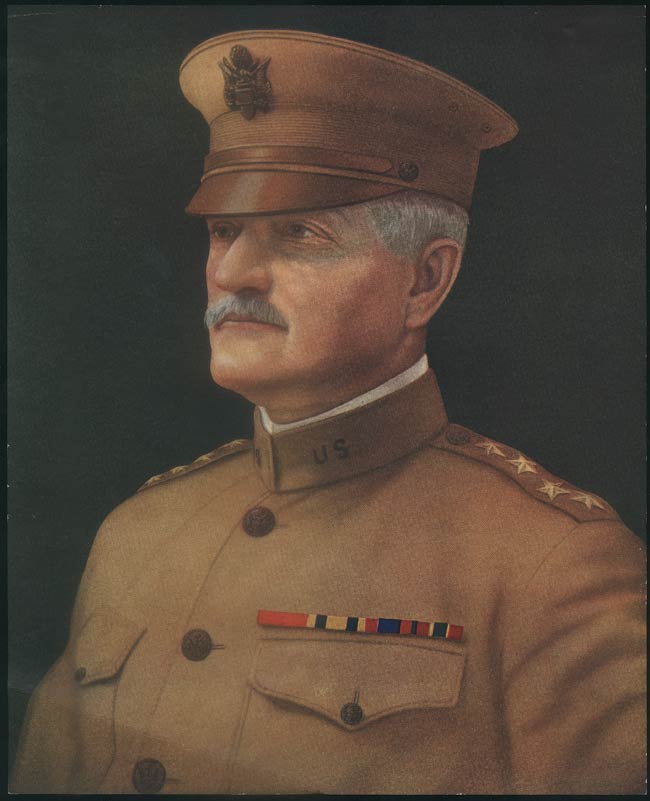

John J. Pershing

Introduction

John J. Pershing was one of America’s most accomplished generals. He is most famous for serving as commander of the American Expeditionary Forces in World War I. These troops from America bolstered the spirits of European allies and helped defeat the Central Powers in 1918. Congress promoted Pershing to the rank of “General of the Armies of the United States” in 1919. He and George Washington are the only two people who have received this honor.

Early Years and Education

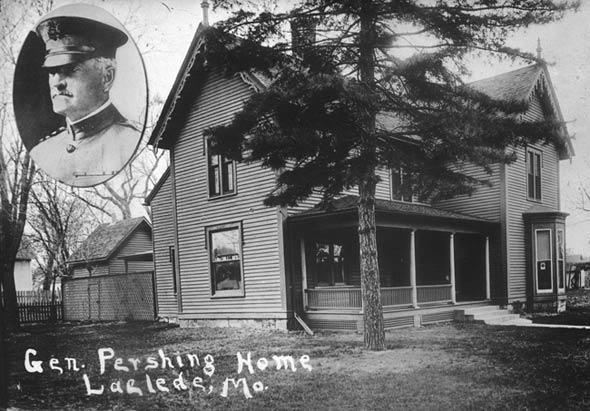

On September 13, 1860, John Joseph Pershing was born near Laclede, Linn County, Missouri. He was the first child born to John Fletcher Pershing and Ann Thompson Pershing. John had eight younger siblings, but only five survived to adulthood: May, Elizabeth, Grace, Ward, and James. His father owned a general store and served as postmaster of Laclede.

In 1873 an economic depression swept across the United States, affecting millions of Americans. John’s father had taken out numerous bank loans to purchase area farmland. When the Panic of 1873 hit, the elder Pershing was unable to pay back the loans and watched helplessly as the banks foreclosed on all but one of his farms. The Pershings lost almost all of their wealth. John’s father was forced to take a job as a traveling salesman. Fourteen-year-old John was put in charge of the family while his father was on the road. He was expected to make the family farm profitable and attend school.

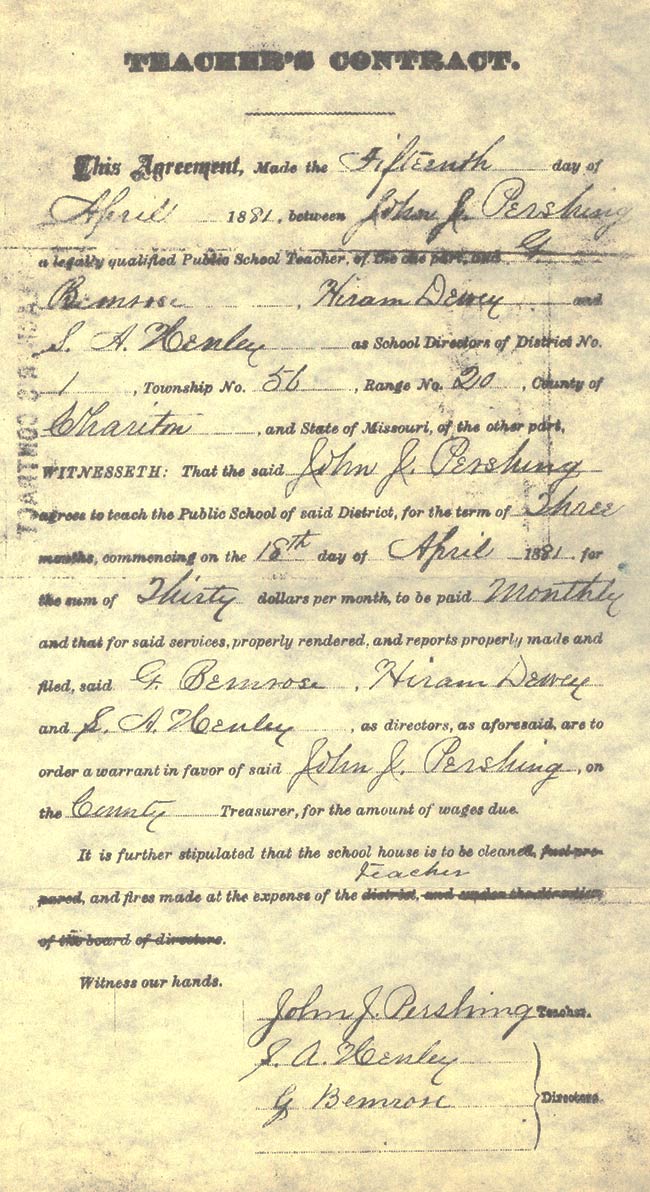

John’s family could not afford to send him to college, so he took a job as a teacher at Prairie Mound School in Chariton County, Missouri. Once he had saved enough money, John enrolled at Kirksville Normal School (now Truman State University). He graduated in 1880 with a teaching degree. John returned to Prairie Mound School after graduation. He soon decided, however, that he wanted to be a lawyer and returned to Kirksville to study law.

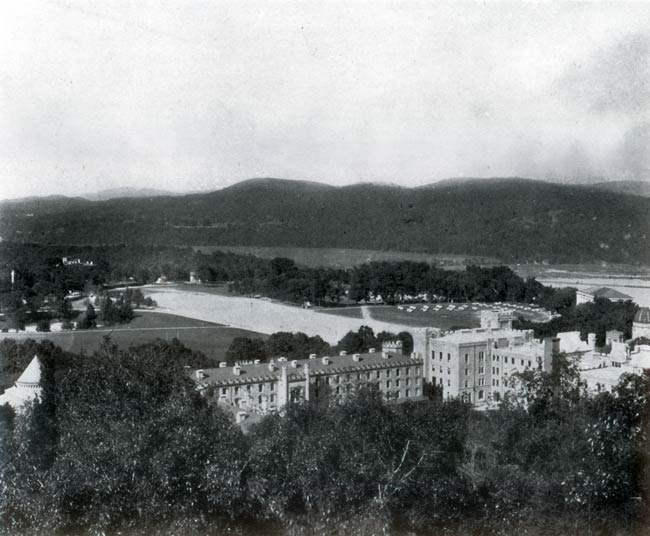

After reading an advertisement announcing an entrance exam for the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, John decided to take the test to earn a free education. His sister Elizabeth helped him study. Only one person in the congressional district would win an appointment. Pershing earned the top exam score by a narrow margin and entered West Point in July 1882.

While Pershing struggled academically his first year at West Point, he was determined to succeed. Although he graduated thirtieth out of a class of seventy-seven in 1886, he was elected class president four years in a row.

Early Military Career

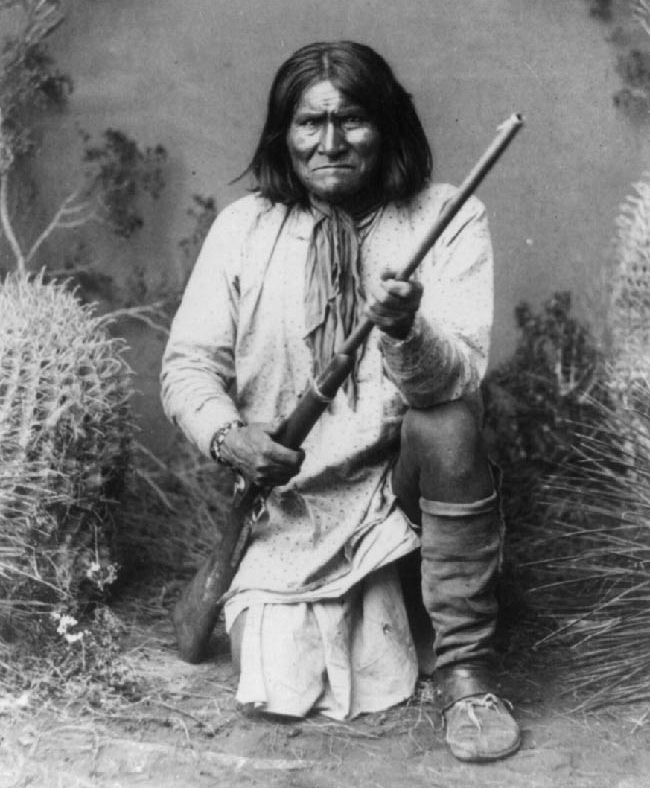

After graduation, Pershing was assigned to the Sixth Cavalry and spent the early years of his career fighting Native Americans to protect white settlers. In his first assignment with the Sixth Cavalry, he was stationed in New Mexico and Arizona where he fought Apaches led by Geronimo.

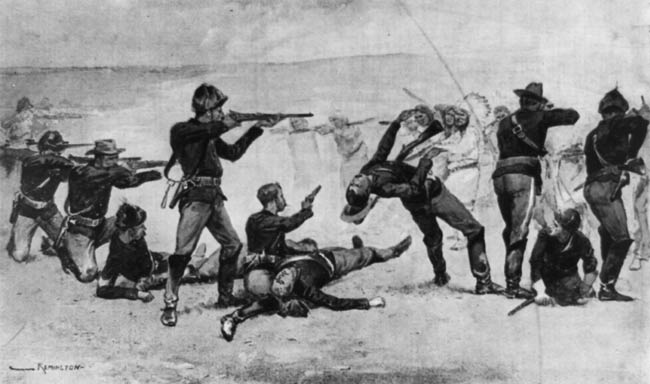

Pershing next participated in the campaign to subdue the Sioux, or Lakota, tribes in the Dakota Territory where the U.S. government sought to eliminate the Ghost Dance, a Native American religious movement. A confrontation at Wounded Knee between the Lakota and the military resulted in gunfire. Between 200 and 300 Sioux men, women, and children were killed, along with 25-30 soldiers. The incident later became known as the Wounded Knee Massacre. Although Pershing did not participate in the battle, he helped establish and maintain a perimeter to keep the Lakota from fleeing.

During his time in the West, Pershing learned some of the Apache dialects and Plains sign language, which helped foster the respect he held for the Native Americans. He maintained his enthusiasm for learning about his adversaries throughout his military career.

While serving a four-year stint as a professor of military science at the University of Nebraska, Pershing earned a law degree in 1893. He later told a family acquaintance from Laclede that he felt his law degree helped him with his military career.

The Buffalo Soldiers

In 1896 Pershing was assigned to the frontier with the Tenth Cavalry, an all-black regiment. The Native Americans called these troops buffalo soldiers because they believed the soldiers’ hair resembled that of a buffalo. At the time, blacks were segregated from whites in the military.

Pershing was then assigned to teach at West Point. Here he was given the nickname “Black Jack” because he had spent time with the Tenth Cavalry. When the Spanish-American War broke out, Pershing was selected to command the Tenth Cavalry once more and led his men in Cuba at the Battle of San Juan Hill. The bravery and courage shown by the men of the Tenth Cavalry earned them Pershing’s respect and admiration. He often praised the black soldiers to others, an unusual thing to do during this time.

The Philippine Insurrection and a Controversial Promotion

After Spain was defeated in the Spanish-American War of 1898, the United States took control of the Philippines. Beginning in 1899, Pershing was stationed there for three and a half years. While there, he led American forces against several tribes, collectively called “Moros,” who were resisting the United States’ control. The fighting was difficult and flared off and on for several years. During his time in the Philippines, Pershing learned the Moros’ language and studied their customs, which helped him gain their respect and confidence. One of the tribes even named Pershing a minor noble.

After returning from his first tour in the Philippines, Pershing met and married Helen Frances Warren, the daughter of U.S. Senator Francis E. Warren of Wyoming. They had four children: Helen, Ann, Warren, and Margaret.

President Theodore Roosevelt promoted Pershing in 1906 to brigadier general, a jump in rank of four grades. The promotion was controversial because Pershing bypassed more than eight hundred senior officers. Many within the military thought he had received the promotion because he was married to a senator’s daughter. President Roosevelt, however, had suggested the promotion three years earlier, before Pershing had met the Warren family.

Pershing returned to the Philippines for a second tour from 1906 to 1913. Once again, he used force and his knowledge of his adversaries to quiet the rebelling Moro tribes.

Family Tragedy

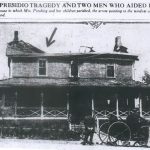

In late 1913 Pershing and his family moved to San Francisco where he commanded the Eighth Brigade. Two years later, while Pershing was on assignment in Texas, he received the news that his wife and daughters had been killed in a fire. Only his six-year-old son, Warren, survived. Pershing was devastated by the loss, and those who knew him said he never fully recovered. He distracted himself by becoming immersed in his work. Pershing’s sister May was put in charge of Warren’s care and upbringing.

Going After Pancho Villa

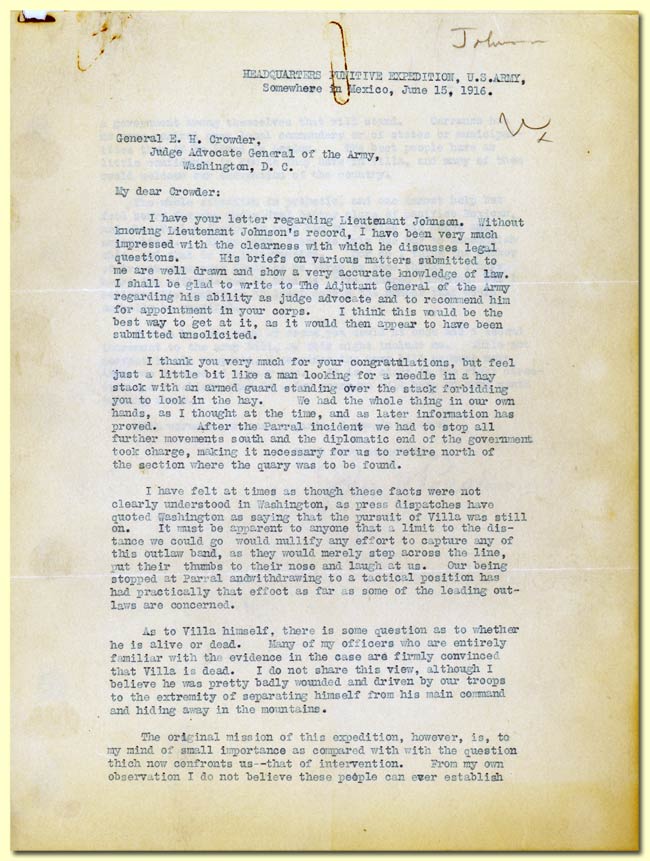

On March 9, 1916, Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa and his men raided the border town of Columbus, New Mexico, where eighteen American soldiers and civilians were killed and ten others wounded. In response, President Woodrow Wilson ordered Pershing to capture Villa.

The expedition into Mexico began on March 15, 1916. Pershing and his soldiers experienced harsh conditions. Their supplies soon ran low, and the Mexican government forbade them from using rail lines to transport troops and supplies. The terrain was extremely rugged and mountainous. The area was also unmapped and had no roads, so the expedition had to rely on local guides.

Several skirmishes took place that resulted in the U.S. military restricting Pershing’s movements. President Wilson worried that a war might start. Eventually, Pershing was ordered to stop the expedition. This greatly frustrated him as he had spent almost a year in Mexico pursuing Villa, but was never able to catch him. Pershing described the failed mission as “a man looking for a needle in a hay stack with an armed guard standing over the stack forbidding you to look in the hay.”

The Great War

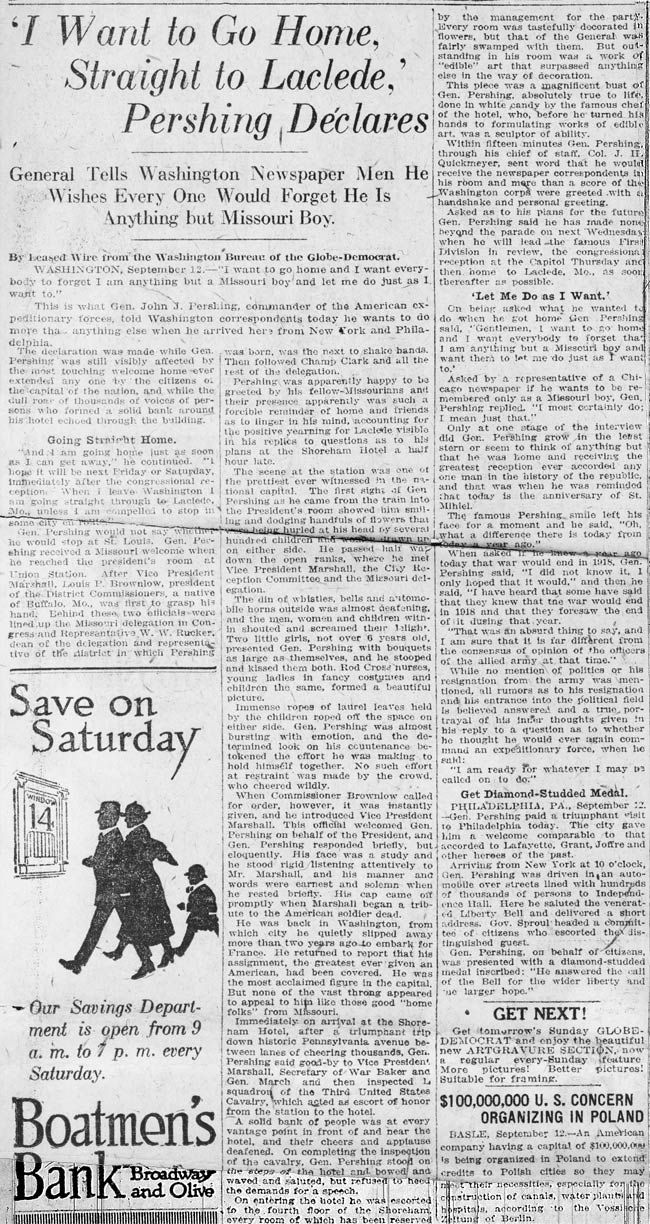

After the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria in 1914, Europe erupted into World War I. While the continent quickly sank into one of the most deadly wars in history, the United States did not become involved right away. At the time, the country had a policy to remain neutral during conflicts. The United States finally entered the war in 1917.

Pershing was appointed commander of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF), the military force sent to Europe. General Pershing faced many challenges as the United States’ standing army swelled from slightly less than 130,000 men to 2,000,000 in just eighteen months. He had to make many decisions, such as how large the AEF should grow, how to organize supplies, where the AEF should fight in Europe, and when his troops would be ready for combat. America’s European allies were eager for the war to end and demanded that American troops be prepared to fight as soon as they arrived.

General Pershing also needed to decide whether or not to lend American soldiers to the European allies. When the AEF arrived in Europe, the Allies were exhausted from three years of war. While some American military personnel and European allies wanted Pershing to send American troops to “fill in gaps” in the Allied armies, he established his authority by refusing to do so. He believed the strategy would not work because the training methods used by the U.S. and the Europeans were too different from each other. He also thought that a united American military force would hurt German morale more. Despite opposition, Pershing stood firm in his decision.

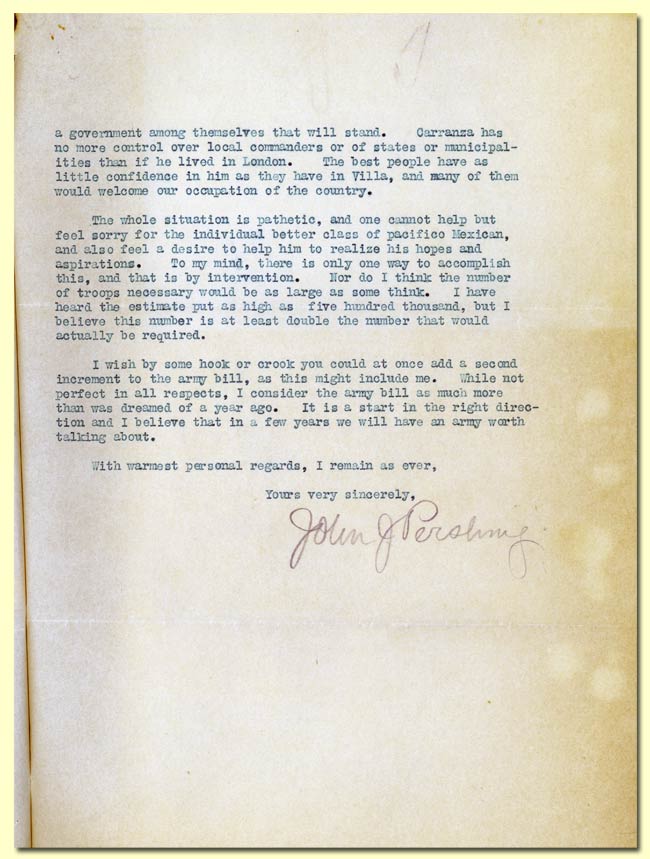

The AEF participated in numerous important battles such as the Battle of Cantigny, the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, and the Battle of St. Mihiel. General Pershing eventually cut the Germans’ lines at Sedan on November 6, 1918. He counted this as one of the AEF’s most important accomplishments. On November 11, 1918, World War I ended, due to the combined efforts of the AEF and the European allies. General Pershing and his men were celebrated as heroes.

After World War I

In 1919 Congress honored General Pershing by naming him General of the Armies. This special honor allowed General Pershing to be on “active duty” for the rest of his life and continue to be available for assignments.

General Pershing served as Army Chief of Staff from 1921 to 1924. He later oversaw a commission to settle a boundary dispute between Chile and Peru, and he served as a consultant when the United States entered World War II. He also wrote a memoir, My Experiences in World War, which won the Pulitzer Prize for history in 1932.

On July 15, 1948, Pershing died in his sleep from complications of a stroke. His body lay in state in the rotunda of the U.S. Capitol, and an estimated 300,000 people came to see his funeral procession. He was buried with honors at Arlington National Cemetery in Washington, DC.

Pershing's Legacy

Out of all of his numerous military campaigns, General Pershing’s leadership of the American Expeditionary Forces in World War I was his greatest accomplishment. The introduction of the AEF troops helped end World War I, and without the American soldiers, the European allies would have faced an uncertain outcome.

Over the course of his military career, General Pershing commanded several famous Americans, including fellow Missourian and future President Harry S. Truman, General George S. Patton, General and later U.S. Secretary of State George C. Marshall, and General Douglas MacArthur, making General Pershing one of America’s most influential military leaders.

Text and research by Stephanie L. Kukuljan and Kimberly Harper

References and Resources

For more information about John Pershing’s life and career, see the following resources:

Society Resources

The following is a selected list of books, articles, and manuscripts about John Pershing in the research centers of The State Historical Society of Missouri. The Society’s call numbers follow the citations in brackets.

Articles from the Missouri Historical Review

- Epperson, Ivan H. “Missourians Abroad No. 1 – Major General John J. Pershing.” v. 11, nos. 3-4 (April-July 1917), pp. 313-323.

- Smythe, Donald. “The Early Years of John J. Pershing: 1860–1882.” v. 58, no. 1 (October 1963), pp. 1-20.

Articles from the Newspaper Collection

- “General John Joseph ‘Black Jack’ Pershing: The Missourian Awards, 1999.” The (Columbia) Missourian. November 6, 1999. [Reel # 7999]

- “Pershing Avoids Politics During Bombardment by Thirty Newspaper Men.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. September 9, 1919. [Reel # 42108]

Books and Articles

- Christensen, Lawrence O., William E. Foley, Gary R. Kremer, and Kenneth H. Winn, eds. Dictionary of Missouri Biography. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1999. pp. 609-611. [REF F508 D561]

- Dobak, William A. and Thomas D. Phillips. The Black Regulars, 1866–1898. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2001. [REF 357.1 D65]

- “Masonic Portrait: A close look at one of the workers in Freemasonry’s quarries; Brother John Joseph ‘Blackjack’ Pershing.” The Missouri Freemason, Spring 2002. pp. 42-43. [REF F587.1 F877]

- “Missouri’s ‘Black Jack’ Pershing: ‘The Coolest Man Under Fire I Ever Saw.’” Senior Life Times, September 1999. [REF Vertical File]

- O’Connor, Richard. Black Jack Pershing. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1961. [REF F508.1 P43o]

- Palmer, Frederick. Pershing: General of the Armies. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1986. [REF F508.1 P43p]

- Pershing, John J. My Experiences in the World War. New York: Frederick A. Stokes, 1931. [REF F508.1 P43]

- Smith, Gene. Until the Last Trumpet Sounds: The Life of General of the Armies John J. Pershing. New York: Wiley, 1998.

- Smythe, Donald. Guerrilla Warrior: The Early Life of John J. Pershing. New York: Scribner, 1973. [REF F508.1 P43s]

- Welsome, Eileen. The General & the Jaguar: Pershing’s Hunt for Pancho Villa: A True Story of Revolution and Revenge. New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2006.

Manuscript Collection

- Crowder, Enoch H. (1859-1932), Papers, 1884-1942 (C1046)

Correspondence and other papers of a judge advocate general who administered the Selective Service during World War I and served as ambassador to Cuba. References to Pershing can be found throughout the collection. - Lockmiller, David A. (1906-2005), Papers, 1880-1964 (C0405)

This collection contains the papers of General Enoch H. Crowder’s biographer. Crowder was the administrator of the Selective Service during World War I and an ambassador to Cuba. Several letters written by Pershing to Crowder concerning Pancho Villa and World War I can be found in folder 1. - Lomax, Victor W., “Oh Yes, Some Called Him ‘Black Jack’,” n.d. (C3078)

Recollections of John J. Pershing by a native of Laclede, MO, Pershing’s home town. - Lomax, Victor W., Papers (C4270)

Correspondence, photographs, newspaper clippings, and questionnaires concerning General John J. Pershing, Pershing Memorial State Park, and World War I. - State Historical Society of Missouri, Typescript Collection (C0995)

Item #70 of this collection contains a statement of Pershing’s military service by the Adjutant General’s Office of the War Department.

Outside Resources

These links, which open in another window, will take you outside the Society’s website. The Society is not responsible for the content of the following websites:

- Arlington National Cemetery

This website contains a biography of Pershing with photographs. - Firstworldwar.com

A multimedia history of World War I can be found at this website. - Pershing Museum

This website run by the Pershing Park Memorial Association includes a brief biography on Pershing and information about the different sites in Missouri memorializing Pershing.