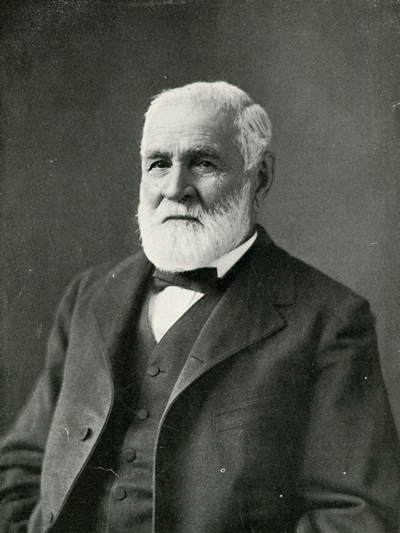

Joseph LaBarge

Introduction

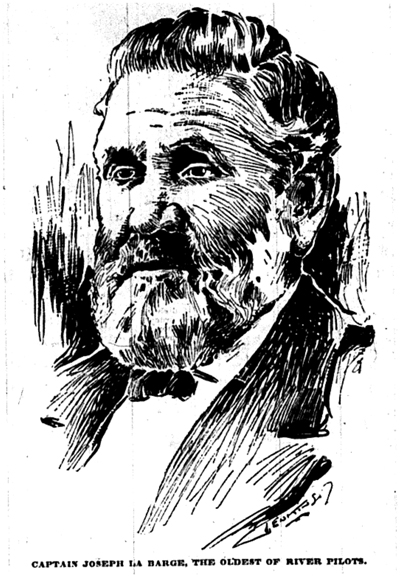

Joseph LaBarge was a famous steamboat captain on the Missouri River. During his fifty-year career, he never lost a boat. LaBarge’s career on the river mirrored the rise and decline of the steamboat industry as interstate river commerce grew until it was eclipsed by the emerging railroad industry.

Early Years and Education

Joseph LaBarge was born on October 1, 1815, to Joseph Marie and Eulalie Hortiz LaBarge in St. Louis, Missouri, the second of seven children. Joseph’s parents personified the cultural diversity of early St. Louis. His father, a French Canadian, immigrated to St. Louis in 1808 and worked as a fur trader. His mother was the daughter of a Spanish military attaché who served as secretary to the last two Spanish lieutenant governors of the Upper Louisiana Territory.

Joseph grew up on a farm on the outskirts of north St. Louis. At school he learned to speak English, as his family spoke French, the primary language used in the Upper Louisiana Territory during his youth. He spent three years as a student at St. Mary’s College in Perry County, Missouri, before leaving at the age of fifteen to begin working. Bored with his job as a store clerk, he joined the crew of the steamboat Yellowstone as a clerk. The following spring, LaBarge signed a contract with the American Fur Company to work as a clerk for $700 for three years. He once again boarded the Yellowstone and traveled up the Missouri River to Council Bluffs, Iowa, and spent the next few years working in the western fur trade.

The Age of the Steamboat

When overtrapping led to the decline of beavers in the eastern United States, merchants, fur traders, and fur trappers like Manuel Lisa and the Chouteau family of St. Louis expanded west up the Missouri River in search of new, unexploited beaver populations. Trading posts sprang up along the river in what is now South Dakota, North Dakota, and Montana. Native Americans brought beaver pelts and buffalo hides to exchange for goods like guns, blankets, and cloth while fur traders dropped off their furs to be shipped to St. Louis for market and picked up supplies. The fastest way to ship furs and travel from the Upper Missouri region to St. Louis was to travel by steamboat, a new form of transportation developed in the early 1800s, as the transcontinental railroad did not exist yet.

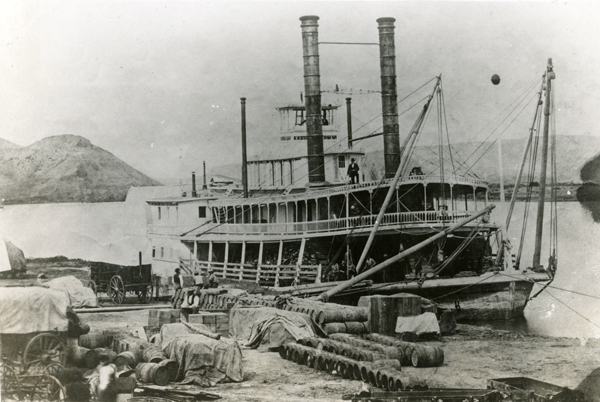

Prior to the steamboat, travelers used a variety of boats such as canoes, keelboats, mackinaws, and bullboats to go up and down the river. These boats were powered by human, wind, or river current, whereas a steamboat is powered by a steam engine and propelled forward by paddlewheels mounted on the rear or sides of the boat.

Prior to channeling in the twentieth century, the Missouri River was not very deep, so steamboats were designed with a long, broad hull for operating in shallow water and had multiple decks with a pilot house on top. The pilot house is where the boat’s wheel, used to steer the boat, was located. The pilot stood at the wheel watching the river ahead, ready to steer the boat away from any obstacles. Steamboats required lots of wood to fuel the fire needed to create steam to power the boat’s engine. Steamboats with paddlewheels mounted on the back were called sternwheelers, while those with paddlewheels on the sides of the boat were known as sidewheelers.

The captain managed the business affairs of the boat while the pilot was responsible for navigation. Some captains also served as pilots; others did not. Captain LaBarge did both. Mark Twain, who grew up on the Mississippi River in Hannibal, idolized steamboat pilots, writing, “A pilot, in those days, was the only unfettered and entirely independent human being that lived in the earth.”

Danger on the River

Steamboat pilots like LaBarge confronted a variety of problems on the river: submerged trees, gravel bars, ice, violent thunderstorms, and even attacks by Native Americans. If a boat became snagged on a tree or other obstruction, it could be lost. Pilots constantly watched for anything that could damage the boat and carefully navigated sharp bends, swift rapids, and other boats. Over time, an experienced pilot memorized the river but floods and high water continually reshaped it, creating new obstacles. Mother Nature, however, was not the only source of concern for steamboat crews. Both steamboat passengers and crew members had to worry about mechanical problems, the most serious of which was a boiler explosion.

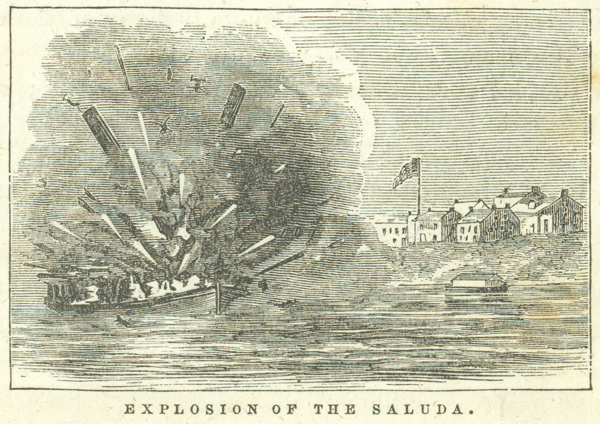

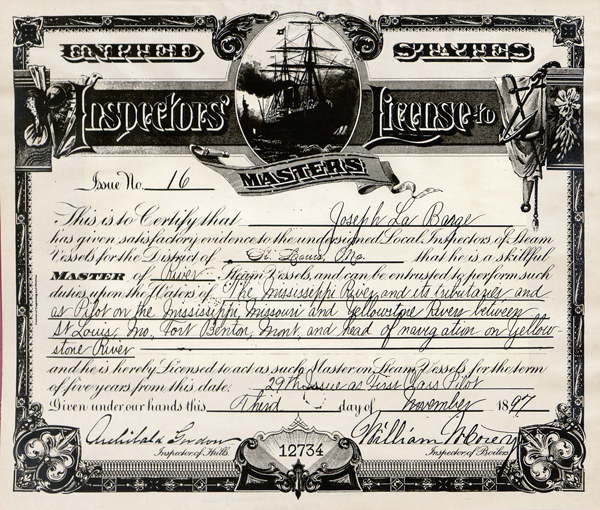

In 1852 the steamboat Saluda suffered a catastrophic boiler explosion as it left Lexington, Missouri. Dozens of passengers were killed, including LaBarge’s brother and brother-in-law, who were working as pilots on the Saluda. Fire was another worry. Because they were made of wood, boats could be set on fire and destroyed by a misplaced cigar or spark. After the passage of the Steamboat Act of 1852, the federal government began regulating the steamboat industry to help prevent passenger deaths from accidents such as fires, collisions, and explosions. Captains and pilots had to earn their licenses, which could be revoked for safety violations.

Steamboat Pilot

LaBarge’s first experience piloting a steamboat occurred in 1833 when passengers on the Yellowstone became ill with cholera. Many of the passengers and crew died, including the pilot, engineer, and fireman. The boat’s captain returned to St. Louis to hire a new crew, leaving LaBarge in command. When settlers living near the river heard that the Yellowstone had experienced a cholera outbreak, they threatened to burn the steamboat unless it was moved away from their settlement. Without any assistance, LaBarge fired up the boilers and moved the boat upstream away from harm. After his contract with the American Fur Company ended, LaBarge began working on steamboats full-time in various positions and developed a reputation as a skilled pilot.

On August 17, 1842, LaBarge married Pelagie Guerette. The couple had seven children together: five boys and two girls. The following year, La Barge served as pilot of the steamboat Omega. Among the passengers was distinguished naturalist and artist John J. Audubon, who was on his final trip west to study and document American wildlife.

By 1845 boat traffic on the Missouri River was growing as steamboats now carried not just furs and supplies but also artists, settlers, missionaries, Native Americans, miners, explorers, enslaved people, scientists, and fur traders, leading some to call it the “Highway of the Plains.” Some of the steamboats that carried passengers became more luxurious, while others remained devoted to hauling cargo. In 1846 LaBarge purchased his first steamboat, the General Brooks, for $12,000—the rough equivalent of over half a million dollars today. He sold it the next year and built a new steamboat, the Martha. Over the years, LaBarge owned or leased a number of boats.

Like many steamboat captains, LaBarge often contracted with the American Fur Company to transport passengers and freight up the river; other times he worked for the federal government or even chose to work for himself. No matter the job, LaBarge met a wide variety of people on board his boat.

In 1851 LaBarge piloted the steamboat St. Ange up the Missouri to Fort Union with Father Pierre De Smet, a famous Catholic missionary, as one of his passengers. That same year, at the age of thirty-six, LaBarge decided to retire. His retirement was short-lived, however, and he had the honor of transporting Abraham Lincoln, not yet president, on one of his boats during Lincoln’s 1859 visit to Council Bluffs, Iowa. In 1861 LaBarge and some partners founded LaBarge, Harkness & Company, whose main rival was the American Fur Company.

Civil War Years

During the Civil War, Captain LaBarge remained loyal to the Union. On one occasion, his life was threatened when a group of Southern sympathizers traveling on LaBarge’s steamboat cheered for Confederate President Jefferson Davis while leaving St. Joseph for Leavenworth, Kansas. Thinking LaBarge was disloyal, a group of Leavenworth residents threatened to hang him when the steamboat arrived, but he was warned in time by his friend Alexander Majors, one of the cofounders of the Pony Express.

On another occasion, Confederate general John S. Marmaduke seized LaBarge, his crew, and his steamboat at Boonville and forced him to transport Sterling Price, another Confederate general who was ill, to Lexington, Missouri. The episode got LaBarge into trouble with Union authorities, but he continued to operate on the river for the rest of the war.

In 1862 LaBarge, who was piloting his boat the Emilie, encountered an American Fur Company boat, the Spread Eagle. The two raced to see which boat could go the fastest. When the captain of the Spread Eagle discovered he was going to lose, he rammed his boat into the Emilie. Angered by such reckless action, LaBarge threatened to shoot the other captain unless he stopped his engines, which he promptly did. The Emilie was badly damaged, and the captain of the Spread Eagle later lost his pilot’s license due to his irresponsible behavior.

The following year, LaBarge contracted with the federal government to transport goods promised to Native Americans upriver to Fort Pierre, Dakota Territory. Upon arrival, the government officials in charge of distribution did not give the Sioux Indians all of their goods. Angered by the agents’ deception, the Sioux followed LaBarge’s steamboat over six hundred miles, shooting at passengers. At a place called Tobacco Garden in what is now North Dakota, 1,500 Sioux waited to ambush the boat, but were repelled by the crew. The remaining goods were stored in an American Fur Company warehouse at Fort Union, Dakota Territory, and were to be picked up the next year by LaBarge. When he returned to pick up the goods, LaBarge discovered the American Fur Company had sold them, leaving him with a $20,000 loss. Within a short period, LaBarge, Harkness & Company went out of business, leaving LaBarge $100,000 in debt.

End of an Era

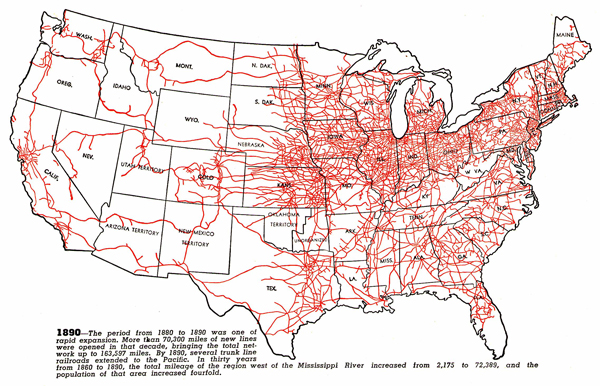

LaBarge continued to work as a captain and pilot, but by the 1860s the golden age of the steamboat was over. In 1869 the first transcontinental railroad in the United States was completed, connecting Council Bluffs, Iowa, to San Francisco, California. A new era of transportation began as additional rail lines were built, stretching like a spider web across America and making cross-country travel faster and easier. Companies could ship freight between cities and states much more quickly and reliably than ever before for less money. Thirty years later, the steamboat industry had almost disappeared from the Missouri River.

Death and Legacy

In 1885 Captain LaBarge retired from the river. A year later, a St. Louis Board of Trade report stated, “The business on this river [the Missouri] has been more affected by railroad competition, than any other river in the West. Steamboats could not compete with a railroad on either bank, and where in 1866 there were in active service seventy-one Steamers, there are now but seven Steamers and three Tow boats, and these ply only between St. Louis and Kansas City.”

LaBarge worked for the city of St. Louis from 1890 to 1894 and then took a job with the federal government compiling a list of steamboat wrecks on the Missouri River. After an unsuccessful surgery on a neck tumor, Joseph LaBarge died of blood poisoning on April 3, 1899, in St. Louis. He is buried in Calvary Cemetery. LaBarge Rock, a natural rock feature overlooking the Missouri River in Chouteau County, Montana, is named in his honor.

Text and research by Kimberly Harper

References and Resources

For more information about Joseph LaBarge’s life and career, see the following resources:

Society Resources

The following is a selected list of books, articles, and manuscripts about Joseph LaBarge in the research centers of The State Historical Society of Missouri. The Society’s call numbers follow the citations in brackets.

Articles from the Missouri Historical Review

- Bowdern, T. S. “Joseph LaBarge Steamboat Captain.” v. 62, no. 4 (July 1968), pp. 449-469.

Articles from the Newspaper Collection

- “Fortunes in Steamboats and Cargo in the Sands of the Missouri.” St. Louis Republican. January 9, 1898. p. 8. [Reel # 44872]

- “Important from Jefferson City.” St. Louis Tri-Weekly Republican. October 21, 1862. p. 4. [Reel # 41385]

- “Old River Man Dead.” St. Louis Globe-Democrat. April 5, 1899. p. 14. [Reel # 39507]

- “Well Known River Captain’s Demise.” St. Louis Republic. April 4, 1899. p. 5. [Reel # 44881]

Books and Articles

- Casler, Michael M. Steamboats of the Fort Union Fur Trade: An Illustrated Listing of Steamboats on the Upper Missouri River, 1831-1867. Williston, ND: Fort Union Association, 1999. [REF 386.2 C269]

- Chittenden, Hiram M. History of Early Steamboat Navigation on the Missouri River: Life and Adventures of Joseph LaBarge. 2 vols. New York: F. P. Harper, 1903. [REF F540 C44 v. 1-2]

- Gillespie, Michael. Wild River, Wooden Boats: True Stories of Steamboating and the Missouri River. Stoddard, WI: Heritage Press, 2000. [REF F581 G412]

- Hartley, William G., and Fred E. Woods. Explosion of the Steamboat Saluda: A Story of Disaster and Compassion Involving Mormon Emigrants and the Town of Lexington, Missouri, in April 1852. Salt Lake City, UT: Millennial Press, 2002. [REF F581 H255]

- Hunter, Louis C. Steamboats on the Western Rivers: An Economic and Technological History. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1949. [REF 386.3 H917]

- Jackson, Donald. Voyages of the Steamboat Yellow Stone. New York: Ticknor & Fields, 1985. [REF 978 J133]

- Lass, William E. Navigating the Missouri: Steamboating on Nature’s Highway, 1819-1935. Norman, OK: Arthur H. Clark Co., 2008. [REF 386.2 L336]

- Lepley, John G. Packets to Paradise: Steamboating to Fort Benton. Missoula, MT: Pictorial Histories, 2001. [REF 386.2 L557]

- The Rivermen. New York: Time-Life Books, 1975. [REF 386 T482]

- Sunder, John E. The Fur Trade on the Upper Missouri, 1840-1865. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1965. [REF F543 Su72]

- Twain, Mark. Life on the Mississippi. New York: Bantam Books, 1963. [REF IC591 S1 1963]

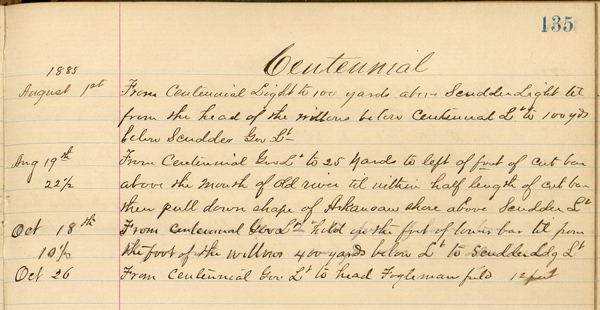

Manuscript Collection

- Edmund Gray Papers (C3611)

Mississippi River pilots’ charts, ships, logs, steamboat directions, and personal papers of Edmund Gray, a resident of Gray’s Point, Scott County, Missouri, and Cape Girardeau and a steamboat pilot on the Mississippi for many years. - James T. Thorp Scrapbooks (C1429)

The scrapbooks contain materials collected and organized by Thorp as histories of the Missouri River, steamboats, and Miami, Missouri. The focus of the collection is the photographs. The photos in volumes 1-3 document over one hundred steamboats, packets, ferries, towboats, snagboats, and excursion boats. - E. B. Trail Collection (C2071)

Correspondence, bills of lading, notes, photographs, clippings, periodicals, scrapbooks, account books, freight books, cabin registers, and portage books of E. B. Trail, Berger, Missouri, dentist and collector of the history and memorabilia of steamboating on the Missouri River and its tributaries. References to Joseph LaBarge can be found throughout the collection.