Lewis and Clark

Introduction

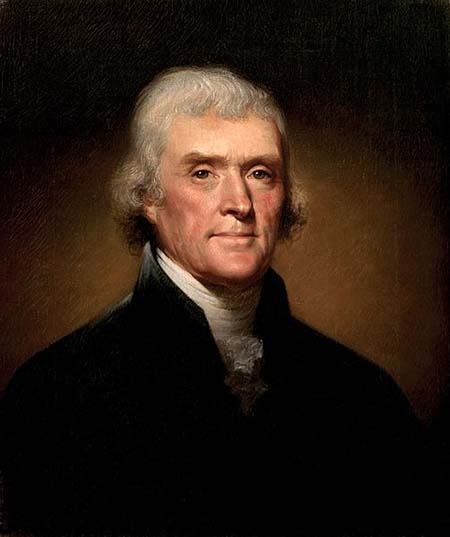

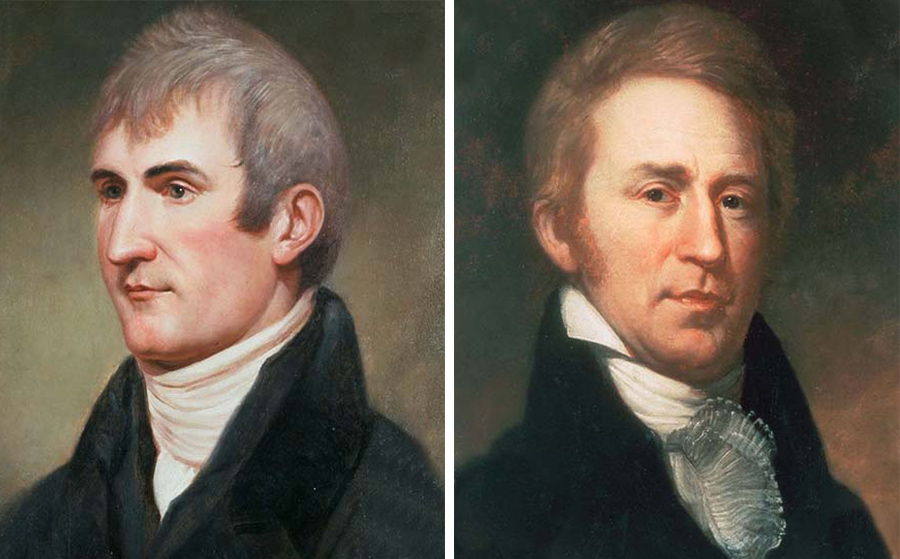

William Clark and Meriwether Lewis are the most famous explorers in U.S. history. In 1804, at the request of President Thomas Jefferson, the men led a two-year overland expedition from Missouri to the Pacific Ocean.

Early Life and Education

William Clark was born on August 1, 1770, in Caroline County, Virginia. He was the ninth of ten children born to John and Ann Rogers Clark. Although too young to have served during the American Revolution, five of his older brothers fought against the British, one of whom was famed frontiersman and brigadier general George Rogers Clark.

After the end of the war, William and his family moved to a farm near Louisville, Kentucky. Unlike his brothers, who had attended school in Virginia, William was home-schooled. Although he could read and write, Clark struggled with spelling errors and inconsistent capitalization throughout his life. In 1789 Clark joined the militia and fought in several campaigns against Native Americans. Finding military life to his liking, Clark earned a commission as an officer in the regular army.

Meriwether Lewis was born on August 18, 1774, at Locust Hill plantation in Albemarle County, Virginia. Coincidentally, Lewis was born within riding distance of President Thomas Jefferson’s home, Monticello. He was the son of William and Lucy Meriwether Lewis. William Lewis passed away when Meriwether was only five years old.

After Lucy Lewis married John Marks, the family moved to Georgia. Meriwether soon returned to Virginia where he received a basic education. He spent his spare time outdoors and enjoyed studying natural history. Like Clark, he joined the militia and later became an officer in the regular military. The two men met while in the military and struck up a lifelong friendship. In 1801 Lewis was selected by Thomas Jefferson to serve as his private secretary shortly before Jefferson was elected president.

Louisiana Purchase

In 1803 U.S. President Thomas Jefferson oversaw the United States’ purchase of the Louisiana Territory from France for $15 million. The acquisition doubled the size of the country—it now stretched west of the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains. Eager to learn more about the region, Jefferson placed Captain Meriwether Lewis in charge of a military expedition tasked with gathering scientific information about the flora, fauna, geography, and Native Americans in the newly acquired territory. Jefferson also hoped the expedition would locate a waterway linking the Missouri River to the Pacific Ocean.

After receiving his orders from Jefferson, Lewis met with scientists in Philadelphia who tutored him in astronomy, botany, meteorology, natural history, and science to help him better understand and record what he would encounter on the journey west. He also purchased the supplies that the expedition would use during its twenty-eight months in the wilderness.

Corps of Discovery

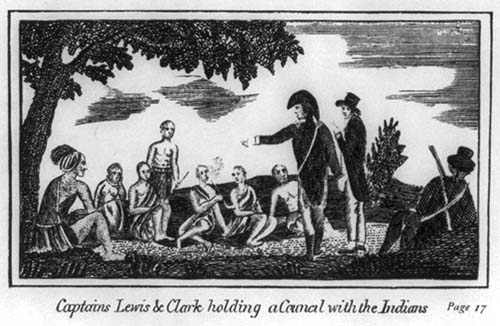

When Lewis asked William Clark to serve as co-commander of the expedition, Clark readily accepted. The two men began recruiting members for what they called the “Corps of Discovery” and signed up over thirty individuals for the expedition.

The men who made up the Corps of Discovery came from many different backgrounds. Among them were German-born John Potts; one-eyed Pierre Cruzatte who was half French, half Omaha; and Kentucky native John Coulter. York, who William Clark enslaved, also accompanied the group, although he was not considered an official member of the expedition. Many of the men possessed special skills such as gun repair, blacksmithing, speaking multiple languages, and even tailoring.

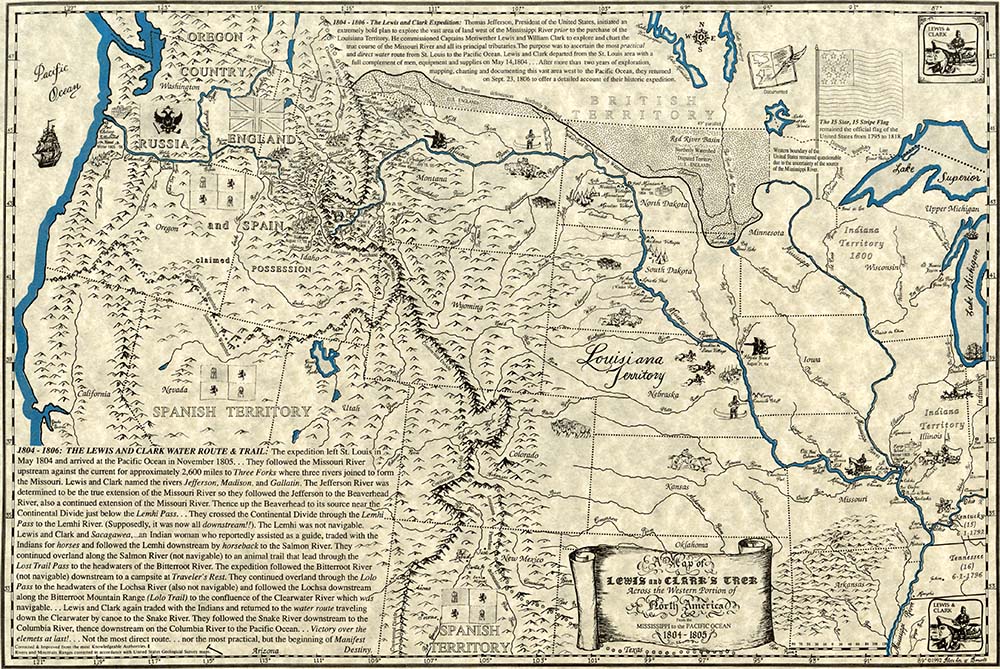

On May 21, 1804, the group left St. Charles, Missouri. They followed the Missouri River through what is now Kansas, Nebraska, Iowa, South Dakota, and North Dakota before stopping to stay with the Mandan and Hidatsa tribes during the winter of 1804.

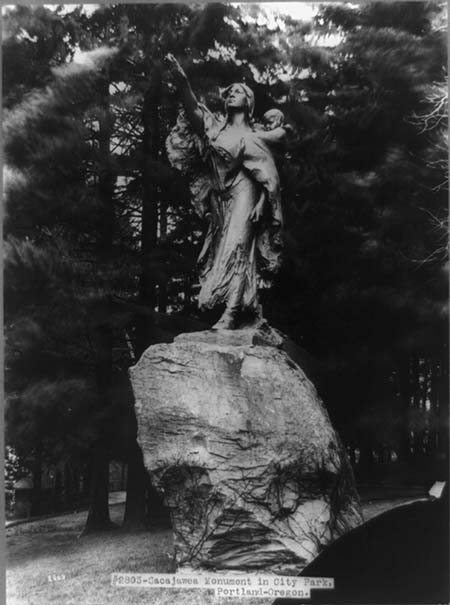

It was then that Lewis and Clark met Toussaint Charbonneau, a French Canadian fur trapper, and his young Lemhi Shoshone wife, Sacagawea. They decided to hire Charbonneau and Sacagawea as interpreters to communicate with Native American tribes they would encounter when they traveled farther west.

Clark was fond of Sacagawea, and she proved to be a valuable asset to the expedition. When one of the group’s boats almost capsized, Lewis and Clark’s journals, maps, and scientific instruments fell into the river, putting the information gathered by the expedition at great risk of being lost. Sacagawea quickly saved the expedition’s papers and instruments from ruin.

In 1805 the expedition reached the headwaters of the Missouri River, crossed the Continental Divide, and then traveled on foot and by canoe to the Pacific Ocean. The Corps of Discovery spent the winter at Fort Clatsop on the Oregon coast. On March 23, 1806, the expedition began the long trek home.

End of the Journey

In two years and three months, the Corps of Discovery traveled 7,000 miles on foot, by boat, and by horse. All but one of the original members of the expedition arrived in St. Louis on September 23, 1806, to an enthusiastic welcome. Sergeant Charles Floyd had died early in 1804 of a ruptured appendix near present-day Council Bluffs, Iowa.

Lewis and Clark, along with five of their comrades, documented their interactions with numerous Native American tribes; collected scientific specimens; and recorded valuable observations about plants, animals, astronomy, Native American culture, and the climate. Their journals were published to wide acclaim, and the maps that they drew expanded previous knowledge of the territory’s geography and waterways.

Government Service

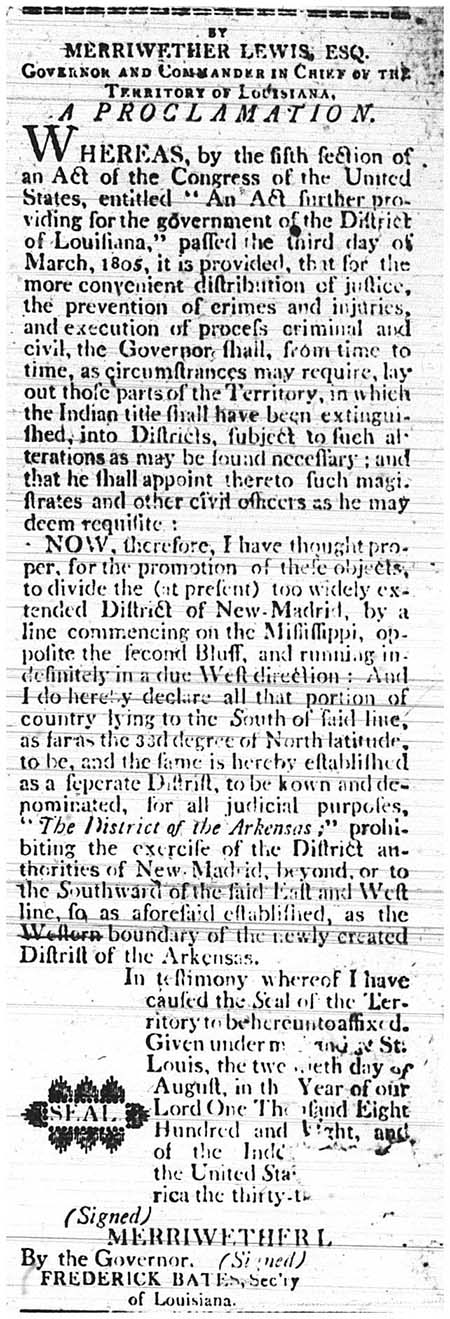

Upon their triumphant return, President Jefferson appointed Lewis governor of the Louisiana Territory and gave Clark a dual appointment as brigadier general of the territory’s militia and principal U.S. Indian agent west of the Mississippi River.

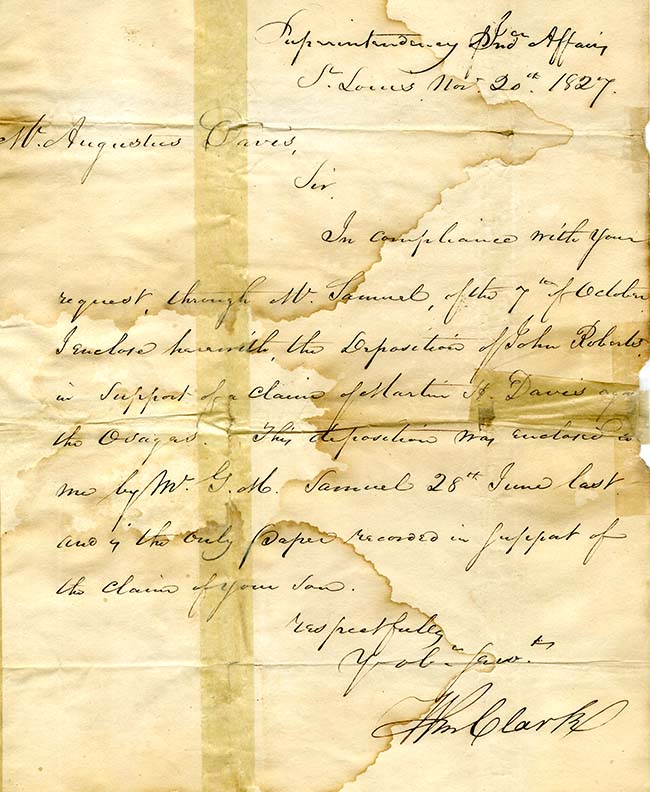

Clark spent much of his time tending to indigenous affairs and countering British influence in the region. During his time as Indian agent, Clark negotiated numerous treaties between Native Americans and the federal government. He persuaded the Osage to sign a treaty that ceded tribal land in Missouri and Arkansas to the government, making way for an eventual new wave of settlers. Clark became one of the founding members of the St. Louis Fur Trading Company along with prominent St. Louis businessmen such as Manuel Lisa and Auguste and Pierre Chouteau.

Clark married Judith Hancock on January 5, 1808. Together the couple had five children. After Judith’s death in 1820, Clark married Harriet Kennerly Radford on November 28, 1821, and had two additional children before her death in 1831.

Unlike Clark, Lewis’s time in St. Louis was not as fruitful. While he was a capable military leader, Lewis was not a gifted politician. He had a stormy relationship with his territorial secretary, Frederick Bates, and found himself confronted with feuding political factions that complicated his job as governor.

Despite these setbacks, Lewis accomplished several important achievements while in office. He oversaw the creation of the territory of Arkansas, established the first post office in St. Louis, and ordered the construction of a road linking St. Louis and New Madrid, Missouri. As a private citizen, Lewis helped finance the St. Louis Missouri Gazette, the first newspaper published west of the Missouri.

A Mysterious Fate

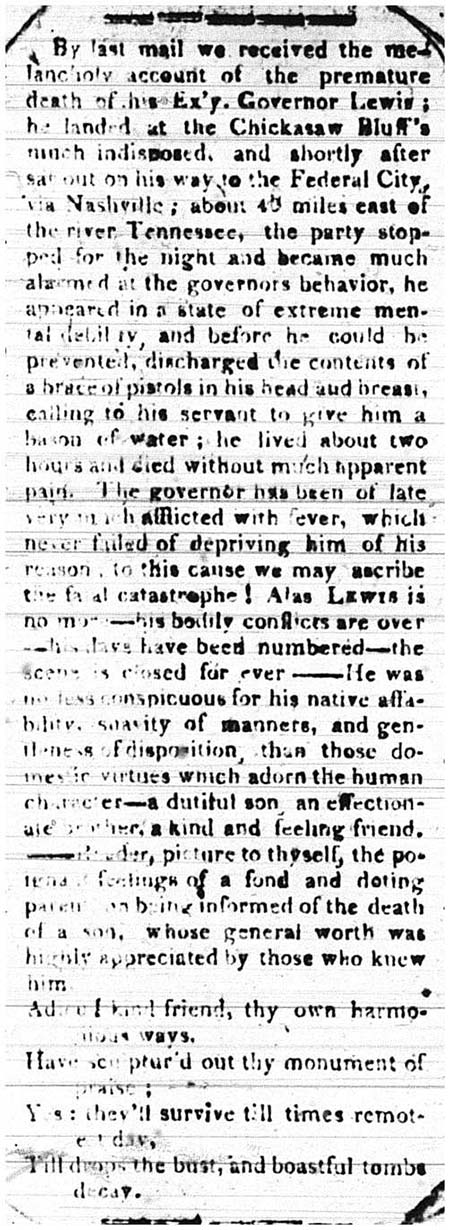

In the fall of 1809, Meriwether Lewis left St. Louis and headed to Washington, DC, to settle financial issues stemming from his time as governor. Traveling along the Natchez Trace, he stopped at an inn at Grinder’s Stand, roughly seventy miles southwest of Nashville, Tennessee.

Although it is unknown exactly what happened, Lewis was found near death the next morning, having been shot twice. He lingered for a few hours before dying the morning of October 11, 1809. He is buried a short distance from where he died along the Natchez Trace Parkway. Historians continue to debate whether Lewis died by suicide or was murdered.

Political Career

In 1813 William Clark was appointed governor of Missouri Territory by President James Madison and served for seven years. His success as an administrator, talent for diplomacy, and concern for his constituents led one historian to call him “Missouri’s best territorial governor.”

When Missouri became a state, Clark ran for governor against Alexander McNair, but lost the election. He retained his position as a U.S. Indian agent and in 1822 was made Superintendent of Indian Affairs at St. Louis, a position he held until his death.

William Clark died at age sixty-eight on September 1, 1838, in St. Louis, Missouri, and is buried in the city’s famed Bellefontaine Cemetery.

Legacy

Although Lewis and Clark were not the first white men to cross North America, the Corps of Discovery captured a glimpse of life before westward expansion changed the landscape and its people forever. Lewis and Clark’s journals remain one of the most vivid accounts of early American exploration, with detailed descriptions of the people, places, and wildlife they encountered during the expedition.

After their return, both Meriwether Lewis and William Clark served admirably during their time in public office. Although Lewis suffered an untimely death, Clark went on to influence the relationship between Native Americans and the federal government during his time as Indian agent. He helped lay the groundwork for settlers to move westward into lands previously owned by Native Americans, shaping the future of generations to come.

Text and research by Kimberly Harper

References and Resources

For more information about the lives and careers of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, see the following resources:

Society Resources

The following is a selected list of books, articles, and manuscripts about Meriwether Lewis and William Clark in the research centers of The State Historical Society of Missouri. The Society’s call numbers follow the citations in brackets.

Articles from the Missouri Historical Review

- Finley, Helen Deveneau, ed. “The Missouri Reader: The Lewis and Clark Expedition, Part I.” v. 42, no. 3 (April 1948). pp. 249-270.

- Finley, Helen Deveneau, ed. “The Missouri Reader: The Lewis and Clark Expedition, Part II.” v. 42, no. 4 (July 1948). pp. 343-366.

- Foley, William E. “The Lewis and Clark Expedition’s Silent Partners: The Chouteau Brothers of St. Louis.” v. 77, no. 2 (January 1983). pp. 131-146.

- Klein, Ada Paris, ed. “The Missouri Reader: The Lewis and Clark Expedition, Part III.” v. 43, no. 1 (October 1948). pp. 48-70.

- Klein, Ada Paris, ed. “The Missouri Reader: The Lewis and Clark Expedition, Part IV.” v. 43, no. 2 (January 1949). pp. 145-159.

- Steffen, Jerome O. “William Clark: A New Perspective of Missouri Territorial Politics, 1813-1820.” v. 67, no. 2 (January 1973). pp. 171-197.

- Wood, W. Raymond. “William Clark’s Mapping in Missouri, 1803-1804.” v. 76, no. 3 (April 1982). pp. 241-252.

Articles from the Newspaper Collection

- “Adjutant General of Missouri.” St. Louis Missouri Gazette. August 24, 1808. p. 3, c. 3. [Reel # 41283]

- “Appointed Governor of Missouri Territory [Clark].” St. Louis Missouri Gazette. July 3, 1813. p. 3, c. 4. [Reel # 41283]

- “Autobiographical Sketch of Gen. William Clark.” Missouri Intelligencer. August 26, 1820. p. 1, c. 5. [Reel # 11512]

- “Candidate for Governor of Missouri [Clark].” Jackson Missouri Herald. July 22, 1820. p. 2, c. 1. [Reel # 15525]

- “Death Notice of Meriwether Lewis.” St. Louis Missouri Gazette. November 2, 1809. p. 3, c. 3. [Reel # 41283]

- “Gov. Meriwether Lewis Reported Very Ill When at New Madrid.” St. Louis Missouri Gazette. October 4, 1809. p. 3, c. 4. [Reel # 41283]

Books and Articles

- Buckley, Jay H. William Clark: Indian Diplomat. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2008. [REF F508.1 C549bu 2008]

- Christensen, Lawrence O., William E. Foley, Gary R. Kremer, and Kenneth H. Winn, eds. Dictionary of Missouri Biography. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1999. pp. 190-193; 486-487. [REF F508 D561]

- Danisi, Thomas. Uncovering the Truth about Meriwether Lewis. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 2012. [REF F508.1 L587da2]

- Danisi, Thomas, and John C. Jackson. Meriwether Lewis. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 2009. [REF F508.1 L587da]

- Denny, James M. Lewis and Clark in the Boonslick. Boonville, MO: Boonslick Historical Society, 2000. [REF F516.4 D428]

- Fausz, Frederick, and Michael A. Gavin. “The Death of Meriwether Lewis: An Unsolved Mystery.” Gateway Heritage. v. 24, nos. 2-3 (Fall 2003-Winter 2004), pp. 66-79.

- Foley, William E. Wilderness Journey: The Life of William Clark. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2004. [REF F508.1 C549fo]

- Gass, Patrick. The Journals of Patrick Gass: Member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Missoula, MT: Mountain Press, 1997. [921 G215m 1997]

- Guice, John D., ed. W. By His Own Hand? The Mysterious Death of Meriwether Lewis. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2006. [REF F508.1 L587gu]

- Harlan, James D., and James M. Denny. Atlas of Lewis & Clark in Missouri. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2003. [REF F516.4 H226]

- Holland, Leandra Zim. Feasting and Fasting with Lewis and Clark: A Food and Social History of the Early 1800s. Emigrant, MT: Old Yellowstone Publishing, 2003. [REF 917.8 H719]

- Holt, Glen E. “The St. Louis Years of Lewis and Clark.” Gateway Heritage. v. 2, no. 2 (Fall 1981), pp. 42-48. [REF F550 M69gh]

- Jones, Landon Y., ed. The Essential Lewis and Clark. New York: Ecco Press, 2000. [REF 917.8 J72]

- Moulton, Gary E., ed. The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983-1987. [Bay Collection]

- Moulton, Gary E., ed. “Lewis and Clark on the Middle Missouri.” Nebraska History. v. 81 (Fall 2000), pp. 90-105. [REF 978.2 N275]

- Rogers, Ann. Lewis and Clark in Missouri. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2002. [REF F516.4 R631 2002]

- Ronda, James P. Lewis and Clark among the Indians. Bicentennial edition. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2002. [REF 917.8 R668 2002]

Manuscript Collection

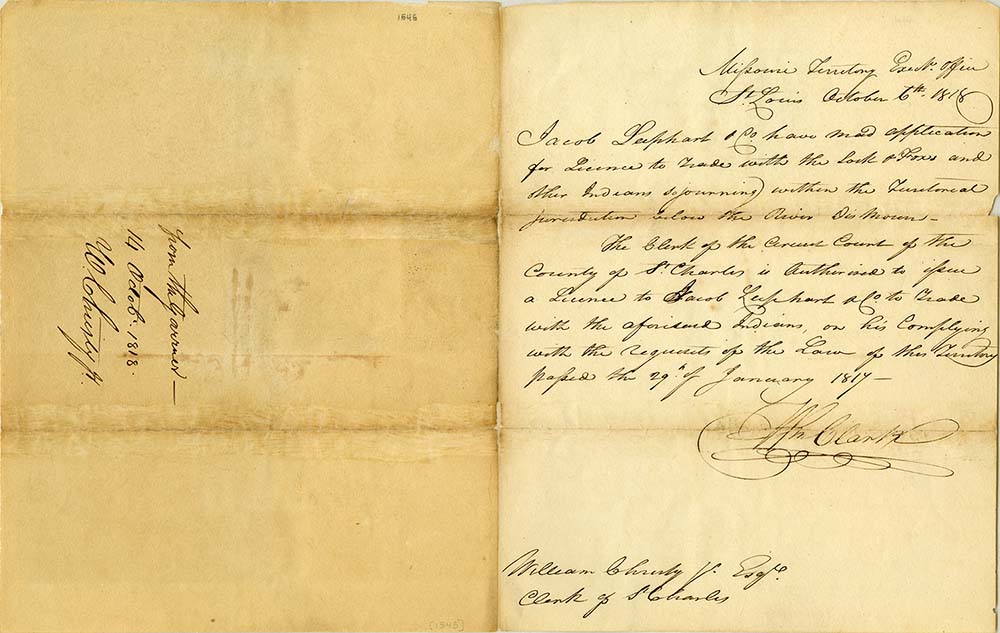

- Clark, William (1770-1838), Letter, 1818 (C1545)

To William Christy, Jr., St. Charles from St. Louis, Oct. 6, 1818. Clark authorized Christy, clerk of the St. Charles Circuit Court, to issue a license to Jacob Laphart & Company for trade with Sac, Fox, and other indigenous tribes below the Des Moines River. - Clark, William (1770-1838), Memorandum Book, 1819-1825 (C1077)

A public account book of William Clark’s, April 1819-1 March 1825, used while he was governor of Missouri Territory and U.S. Superintendent of Indian Affairs. - Clark, William (1770-1838), Memorandum Book, 1826-1831 (C1078)

This book contains rules for Indian agents and lists of 134 drafts drawn between 5 April 1826 and 6 June 1831. - Clark, William (1770-1838), Notebook, 1798-1801 (C1075)

Notes on Clark’s second journey to New Orleans from a starting point in Ohio, 9 March to 16 June 1798, thence from New Orleans to Kentucky, arriving 24 December 1798. Notebook also includes memorandum of distances and expenses on a journey from Kentucky to Philadelphia and back, 1801, and a map of the Mississippi River. - Clark, William (1770-1838), and Meriwether Lewis (1774-1809), Memorandum Book, 1809 (C1076)

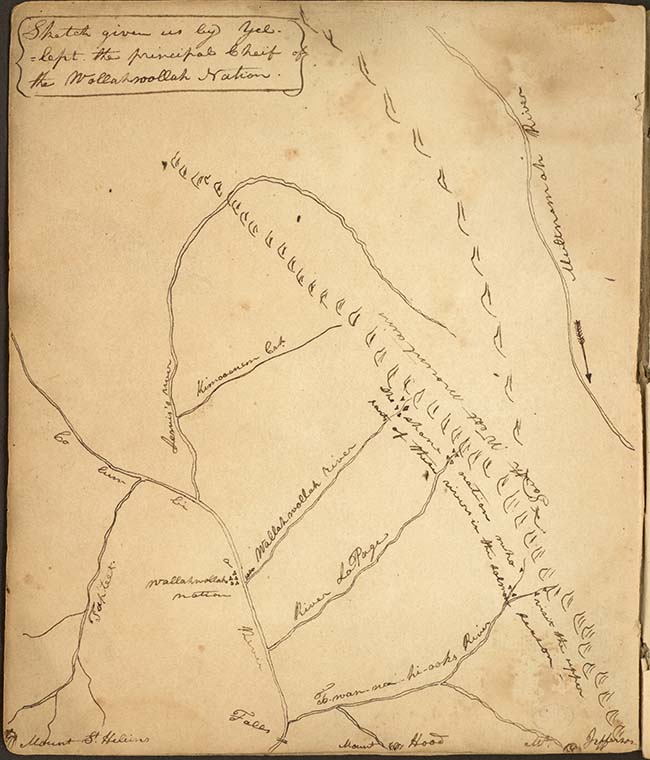

Journal of a trip from St. Louis, Missouri, to Washington, DC. It contains the list of debts due by Clark; the trip expenses from St. Louis, Missouri, and Louisville, Kentucky; a memorandum of instruction by Meriwether Lewis with a list of private debts; and memoranda of drafts and transactions with Indian agencies. - Lewis, Meriwether (1774-1809), Astronomy Notebook [1805] (C1074)

Set of formulae prepared by Robert Patterson of Philadelphia for Lewis to use in determining geographical locations by astronomical observation. Also includes a “sketch given us by Yallept, the principal chief of the Wollah-wollah nation” and a drawing, probably by Lewis.

Outside Resources

These links, which open in another window, will take you outside the Society’s website. The Society is not responsible for the content of the following websites:

- The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition

The full text of the journals of Lewis and Clark can be read for free at this website. Visitors to the site can also browse images of maps and drawings made by the two explorers on their journey. - National Park Service: Lewis and Clark History & Culture

This website offers information about the people, places, and stories that the Corps of Discovery encountered on their journey across the North American continent. Information about traveling the Lewis and Clark Expedition can be found here. Teacher resources are also available.