Mary Jane Guthrie

Introduction

Dr. Mary Jane Guthrie was a professor and researcher at the University of Missouri in Columbia. For nearly thirty years, she taught in the Department of Zoology, and served as its chair from 1939 to 1950. Guthrie undertook pioneering studies on cave bats, and her research on mice helped scientists better understand the origins of cancer.

Early Years and Education

Mary Jane Guthrie was born on December 13, 1895, in New Bloomfield, Missouri, to George and Lula Guthrie. Located in Callaway County, New Bloomfield lies about halfway between Jefferson City and Fulton. The Guthrie family had been in Callaway County since 1819. That year, Mary Jane’s great grandfather, Samuel T. Guthrie, migrated from Kentucky to a place just north of New Bloomfield. Samuel and his wife, Sarah, had fourteen children, including Mary Jane’s grandfather, Robert Ewing Guthrie. In 1872, the site settled by Samuel was officially founded as the town of Guthrie. While the historical records present conflicting views, some suggest that Samuel’s children laid out the town and named it after their family.

Like many people in this area, Mary Jane Guthrie grew up in a farming family. In the 1890s, she lived on a farm owned by her grandfather and his wife, also named Mary Jane. Together, the parents and grandparents worked the land and maintained a household. One of Robert’s nieces, Sara Guthrie, also lived on the farm. Sara earned her living as a teacher, and her income from that job surely helped the family purchase things that could not be grown or made on the farm.

For reasons unknown, George, Lula, and their daughter Mary Jane left New Bloomfield in 1907 and moved to Columbia. George took up work as a carpenter, while Lula took care of the home. Mary Jane attended local schools and graduated from Columbia High School in 1912.

Going to College

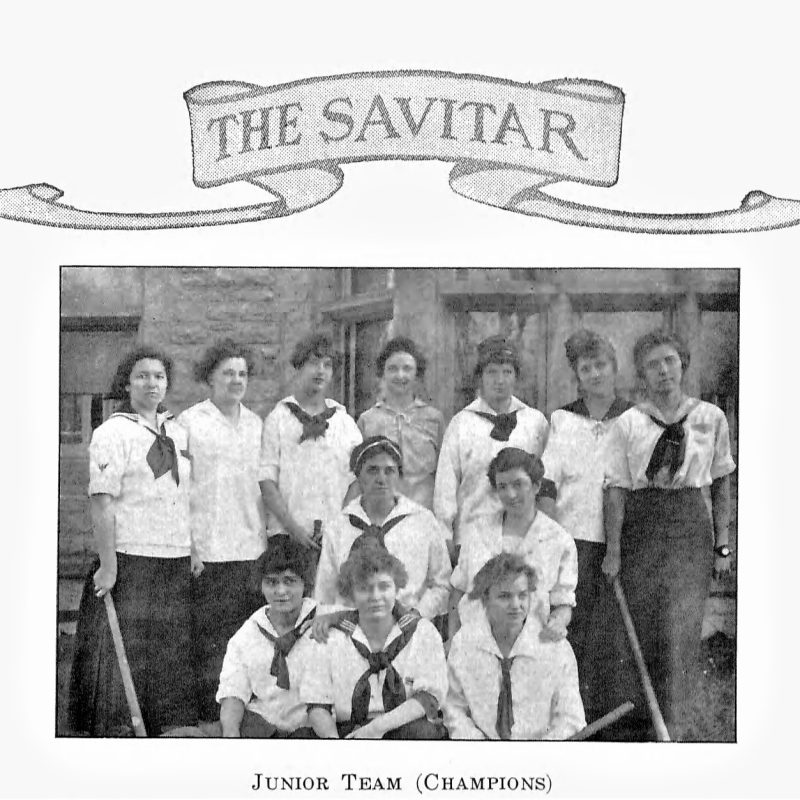

After graduation, Guthrie stayed in Columbia and registered for classes at the University of Missouri. She focused her studies on zoology, a branch of biology that studies and classifies the animal kingdom. Guthrie was also active in university sports. She played on the basketball, field hockey, and baseball teams. After earning her bachelor’s degree in 1916, Guthrie decided to continue her education at the university and began working toward a master’s degree in zoology. As a master’s student, Guthrie devoted her studies to the reproductive system of the green darner, a species of dragonfly. She graduated with her degree in 1918.

After completing her master’s degree, Guthrie entered the PhD program in zoology at Bryn Mawr College, a renowned women’s college outside of Philadelphia. While at Bryn Mawr, Guthrie continued her studies of the reproductive systems of animals, this time examining fish. She also taught in the Zoology Department while pursuing her degree. In 1922, after finishing her PhD., Guthrie returned to the University of Missouri as zoology professor.

Researching Bats at Mizzou

During Guthrie’s time at the University of Missouri, she was a productive and highly regarded researcher. Much of her research during this period focused on the reproductive system of bats and their migratory patterns. In the early 1930s, she undertook the most “comprehensive study of the mammal” made up until that time.

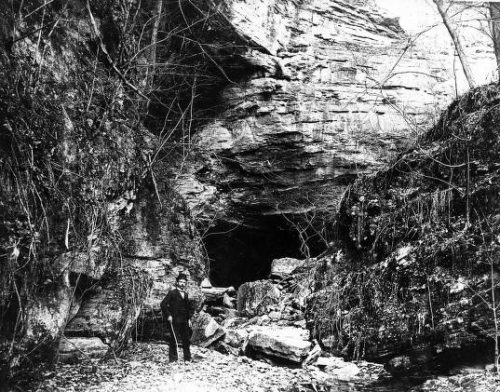

To do this research, Guthrie and a few associates collected bats from two caves near the university. One was called Rocheport Cave, while the other was known as Hunter’s Cave. To capture the bats, one of Guthrie’s colleagues developed a tool called the “bat snatcher.” This snatcher was made by attaching a pair of large forceps, a tool used to hold objects firmly, to a bamboo pole. The forceps were then opened and closed with a lever. The snatcher only worked on bats that were not moving, though. To capture bats in flight, Guthrie and her fellow researchers waited until dusk and stood at the mouth of the caves. Holding large nets, the researchers trapped the bats as they flew out into the night sky. By these methods, Guthrie captured nearly 3,000 bats.

In 1933, Guthrie published two research papers on bats that shed light on a subject that had previously lived in the shadows. Her work uncovered six different bat species active in the region, including a bat that no one knew could be found in Missouri. Her work also found that most bats were migratory, and that in mid-Missouri many bats likely traveled along the Missouri River. She also settled a long-running debate in the field of bat studies about the mating patterns of the nocturnal mammal. Guthrie found that bats mate in both the winter and the spring.

Although Guthrie produced path-breaking research, she sometimes struggled to get the money to perform it. In 1934, she applied for a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation for additional funding to support her research. In order to receive the money, though, an official at the foundation told her that, because she was a woman, she would have to do more to convince them she was a good enough scientist. She apparently met these requirements. In 1934, 1939, and 1940, Guthrie received thousands of dollars from Rockefeller to research Missouri’s bats. Guthrie later said that “women can do anything men can do in science and their ability doesn’t depend on their sex, but upon training, aptitude, and attitude.”

Connecting the Classroom to the Real World

Guthrie was known by her colleagues to be a very efficient person. It was this skill that allowed her to spend her evenings catching bats in Missouri’s caves while also writing zoology textbooks. While at Mizzou, Guthrie coauthored two well-regarded textbooks, the Textbook of General Zoology and Laboratory Directions in General Zoology. Each went through several editions and became standards in teaching zoology.

While Guthrie’s textbooks introduced students to the basics of zoology, she also hoped that they would prepare students to apply their skills and knowledge to the real world. In particular, she hoped that students would be better equipped to combat those who try to discredit or suppress the teaching of science. Good science, Guthrie wrote, “explain[s] facts which can be observed…no legislation, no debate, and no misuse can contribute to its downfall.”

In recognition of Guthrie’s research on bats and her publication of major zoology textbooks, the Department of Zoology promoted her several times. Guthrie was made full professor in 1937, the highest ranking a professor can attain. Then, in 1939, Guthrie was awarded the position of chair, or leader, of the department. She held this position until 1950.

Cancer Research in Detroit

The following year, Guthrie left her long held position at the University of Missouri and moved to Detroit. There, she became a professor at Wayne State University and a researcher at the Detroit Institute of Cancer Research.

While in Detroit, Guthrie studied the development of tumors in mice in order to learn why cells grow in ways that produce cancer. Guthrie focused on the interaction between hormones and ovaries in female mice. Hormones are chemicals that send messages to parts of the body that tell them what to do. Ovaries are the part of the female reproductive system that, among other things, produce eggs. Guthrie discovered that when certain hormones sent from a gland at the base of the brain do not reach the ovaries, tumors can begin to develop. This finding had the potential to help medical professionals detect cancer at an earlier stage of development.

Legacy

Guthrie retired from Wayne State University and the Detroit Institute of Cancer Research in 1961. Although she no longer worked as a scientist for a living, Guthrie remained active in that world. She volunteered at Pontiac General Hospital and served as president of its organization for volunteers from 1965 to 1967. In 1970, she said she hoped to continue to volunteer at hospitals “as long as I can get around.” Mary Jane Guthrie died five years later, on February 22, 1975.

Guthrie’s decades of research and teaching left a major imprint in the field of zoology and beyond. Several times throughout the course of her career, Guthrie was recognized as a notable scientist by the American Men of Science index, a catalogue of scientists across the disciplines doing important research (in 1971, the journal changed its name to American Men and Women of Science). Thousands of students learned about the animal kingdom through Guthrie’s textbooks, and the public’s understanding of became much better because of her willingness to explore caves and capture bats for scientific research. The lessons learned from her research on mice extended beyond that small creature, helping other scientists better understand, and detect, the development of cancer.

Text and research by Doug Genens

References and Resources

For more information about Mary Jane Guthrie’s life and career, see the following resources:

Society Resources

The following is a selected list of newspaper articles about Mary Jane Guthrie in the research centers of The State Historical Society of Missouri. The Society’s call numbers follow the citations in brackets.

- Articles from the Newspaper Collection

- “Sigma Delta Epsilon Elects,” Columbia Missourian. 24 May 1930. p. 4.

- “Seven Students of M.U. Study at Woods Hole,” Columbia Missourian. 29 July 1926. p. 6.

- “Curators Have Busy Session Here Thursday,” Columbia Missourian. 21 July 1934. p. 1.

- “Dr. Mary Guthrie Experiments with Live Bats from Caves,” Columbia Missourian. 11 April 1940. p. 7.

Outside Resources

These links, which open in another window, will take you outside the Society’s website. The Society is not responsible for the content of the following websites:

- Encyclopedia of World Scientists – This book features short biographies of sciences from a variety of disciplines, including Mary Jane Guthrie.

- History of the Department of Zoology – This article, written by University of Missouri zoology professor Winterton Curtis, discusses the early history of the department.

- Notes on the Seasonal Movements and Habits of Some Cave Bats – This article, written by Mary Jane Guthrie, discusses some of her early bat research findings.