Nathaniel Lyon

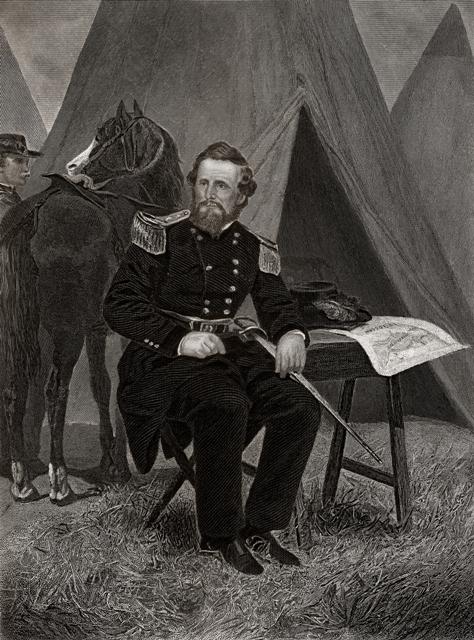

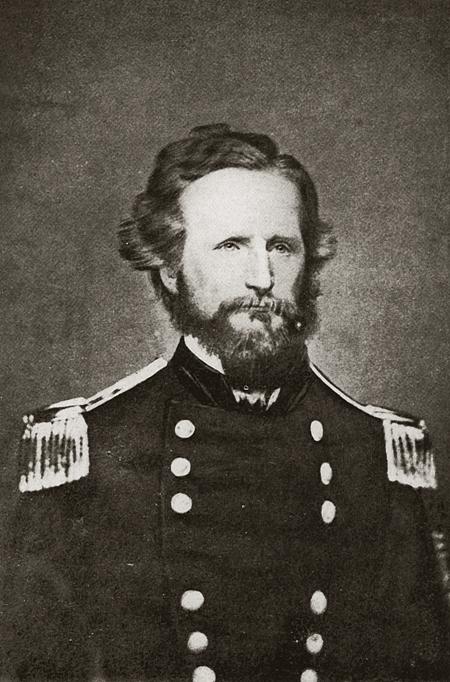

Nathaniel Lyon was a famous Union general in the American Civil War. He was born on July 14, 1818, in Ashford, Connecticut to Amasa and Kezia Knowlton Lyon, the seventh of nine children. His father was a farmer and justice of the peace.

Nathaniel attended school and worked on the family farm. Ambitious from an early age, he decided to pursue a military career. In 1837 Nathaniel received an appointment to the United States Military Academy in West Point, New York. He graduated in 1841 and was ranked eleventh out of a class of fifty-two.

Throughout his life, Lyon exhibited a fiery temper. After serving in Florida during the Second Seminole War, he was transferred to Madison Barracks in New York. While there Lyon was suspended for five months after he beat and later bound and gagged a private for insolent behavior.

After being wounded during the Mexican War (1846-1848), Lyon received a promotion to captain and was ordered to California. While stationed there, he participated in the massacre of Native Americans.

Lyon next served in Kansas where he watched as tensions between pro-slavery and free-soil advocates often erupted into violence. Lyon was not an abolitionist, but he opposed slavery because he believed that enslaved labor created unwanted competition for white laborers. Above all, he believed in the preservation of the United States, and was opposed to states seceding from the Union.

In 1861 the United States stood on the verge of war. Missouri Governor Claiborne Fox Jackson and many members of the state legislature sympathized with the South, and some even favored Missouri’s secession from the Union.

During this confusing period, Lyon was ordered to St. Louis to protect the city’s federal arsenal of gunpowder, thousands of muskets, and several artillery pieces from seizure by pro-Southern forces.

When the Civil War officially broke out on April 12, 1861, St. Louis, like the entire state of Missouri, was divided between pro-Confederate and pro-Union forces. Through political maneuvering, Lyon assumed control of the St. Louis arsenal and its troops. He shipped almost all of the arsenal’s weapons to safety in Illinois. Thousands of untrained volunteers from the city’s German community helped defend the arsenal. Most German immigrants opposed slavery and this stand made them unpopular among many native-born citizens.

Governor Jackson hoped to provoke a confrontation with Lyon and his volunteer troops by ordering the Missouri State Guard to muster for training outside of St. Louis at Camp Jackson. Fearful that the guard was sympathetic to the South, Lyon led his untrained militia on the Missouri State Guard camp. He took prisoners and marched them through the city. Riots broke out in St. Louis when Lyon’s militia fired upon a civilian mob and killed twenty-eight people. This event became known as the “Camp Jackson Affair.”

In response, the state legislature passed a bill giving Governor Jackson authority to prepare the state for war. Thousands of men then joined Missouri State Guard camps across the state. Former Governor Sterling Price, who had remained neutral prior to the Camp Jackson Affair, offered his services to Governor Jackson and was given command of the Missouri State Guard.

Lyon was temporarily removed from command, but was soon made brigadier general of volunteers. He and U.S. Congressman Frank Blair met with Governor Jackson and General Price in an attempt to negotiate peace. The meeting failed.

Jackson, Price, and the Missouri State Guard left St. Louis for Jefferson City. Lyon did not want the state capitol to fall into Confederate hands so he pursued them as they fled west to Boonville.

On June 17, 1861, Union forces skirmished with the Missouri State Guard at the Battle of Boonville. Lyon and his men won easily over the state guard, and this victory was important to the Union because it gave them control of the Missouri River. For the rest of the war, Confederates were unable to use the river to move troops and supplies across the state.

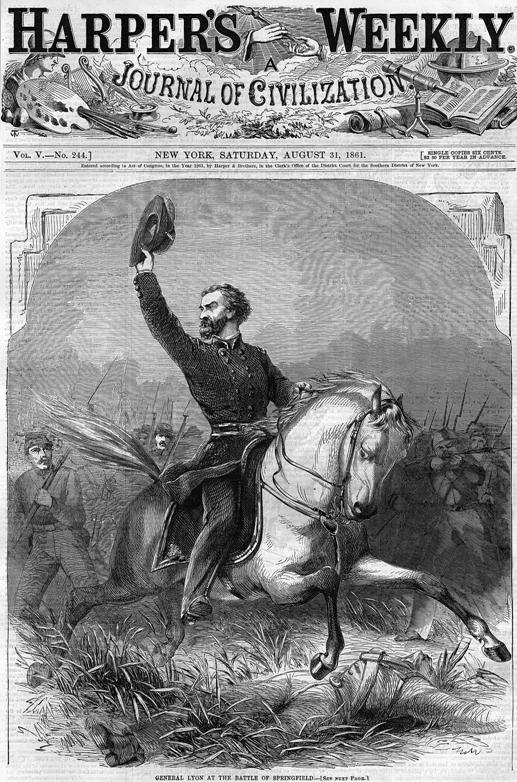

On August 10, 1861, the two sides met again in battle at Wilson’s Creek near Springfield. Lyon was low on supplies and outnumbered because many of his volunteers had recently returned home to St. Louis at the end of their ninety-day enlistment period.

During the battle, Lyon was shot and killed. He was the first general to die in the American Civil War. After intense fighting, Union troops withdrew to Springfield, leaving the exhausted Confederate army behind. Lyon’s corpse was retrieved and sent to Connecticut for burial.

Nathaniel Lyon became a national hero. One of his soldiers remembered, “He struck us as a man devoted to duty, who thought duty, dreamed duty, and had nothing but ‘duty’ on his mind.”

Text by Kimberly Harper with research assistance by Garrett Walker

References and Resources

For more information about Nathaniel Lyon’s life and career, see the following resources:

Society Resources

The following is a selected list of books, articles, and manuscripts about Nathaniel Lyon in the research centers of The State Historical Society of Missouri. The Society’s call numbers follow the citations in brackets.

Articles from the Missouri Historical Review

- Piston, William Garrett. “Springfield is a Vast Hospital: The Dead and Wounded at the Battle of Wilson’s Creek.” v. 93, no. 4 (July 1999), pp. 363-366.

Articles from the Newspaper Collection

- “Burial Account.” Liberty Tribune. August 30, 1861, p. 4 c. 2. [Reel # 26663]

- “Gen. Lyon Killed 64 Years Ago During Battle of Wilson Creek.” University Missourian. August 11, 1925. p. 4, c.4. [Reel # 7596]

- “Gen. Lyon: The Louisville Journal pays the lamented General Nathaniel Lyon, the first great martyr of this unholy rebellion to fall in this State, the following well-merited compliment.” Columbia Statesman. June 12, 1863. p. 1, c. 7. [Reel # 7550]

- “Madness of the Times/Capture of Camp Jackson.” Liberty Tribune. May 17, 1861, p. 2, c. 2. [Reel # 26700]

- “A Relic of War Times: A Letter Written By General Nathaniel Lyon in the Early Days of the Rebellion.” Jefferson City Weekly Tribune. January 18, 1888, p. 6, c. 3. [Reel # 17242]

Books and Articles

- Christensen, Lawrence O., William E. Foley, Gary R. Kremer, and Kenneth H. Winn, eds. Dictionary of Missouri Biography. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1999. pp. 509-510. [REF F508 D561]

- Phillips, Christopher. Damned Yankee: The Life of General Nathaniel Lyon. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1996. [REF F554.1 P541 1996]

- Piston, William Garrett, and Richard W. Hatcher III. Wilson’s Creek: The Second Battle of the Civil War and the Men Who Fought It. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000. [REF F554.1 P678]

Manuscript Collection

- Nathaniel Lyon Letter (C0541)

To A. Fisdale, Lockets Harbor, from Monterey, CA, Apr. 30, 1850. The letter tells of a prospective trip to northern California and Oregon to settle Indian troubles. Mentions the slavery question and local amusements. - John S. Phelps Scrapbook (C3058)

The scrapbook of John S. Phelps contains newspaper clippings and biographical information on the former governor and his family, including an obituary for his wife, Mary Whitney Phelps. She helped keep Nathaniel Lyon’s body safe after he was killed in 1861 at the Battle of Wilson’s Creek.

Outside Resources

These links, which open in another window, will take you outside the Society’s website. The Society is not responsible for the content of the following websites:

- Civil War Preservation Trust: Battle of Wilson’s Creek

This website describes the Battle of Wilson’s Creek. - Community & Conflict: The Impact of the Civil War in the Ozarks

This digital collection contains Civil War documents pertaining to the Ozarks region. The website was created through a partnership of several organizations, including the Springfield-Greene County Library District. - Wilson’s Creek National Battlefield

This U.S. National Park Service provides information for visiting the site of the Battle of Wilson’s Creek.