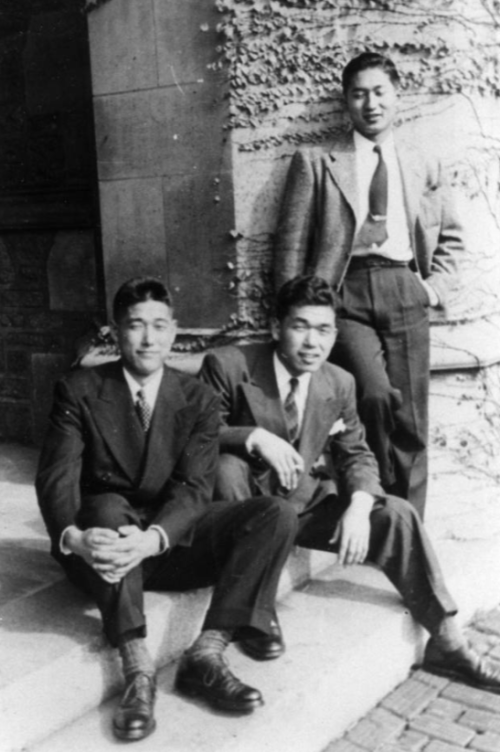

![Henmi Richard Henmi, 1945. [Washington University. The Hatchet. St. Louis: Washington University, 1945. SHS REF 378.778W2 V9 1945]](https://historicmissourians.shsmo.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Henmi-300x400.jpg)

Richard Henmi

Introduction

Richard Henmi was an architect from St. Louis, Missouri. Originally from California, Henmi’s creative designs redefined mid-twentieth-century modern architecture in St. Louis.

Early Years

Richard Henmi was born on January 3, 1924, in Fresno, California, to Soichi and Helen Henmi. His father was born in Japan and immigrated to the United States in the early 1910s. His mother was born in San Jose, California. He had a younger brother named Edward. Growing up in Fresno, Richard attended local schools, and his family ran a grocery store. As a boy, he enjoyed designing model airplanes. Each year he exhibited his latest designs at the Fresno County fair, winning ribbons and trophies. He dreamed of one day working as an aeronautical engineer.

Executive Order 9066

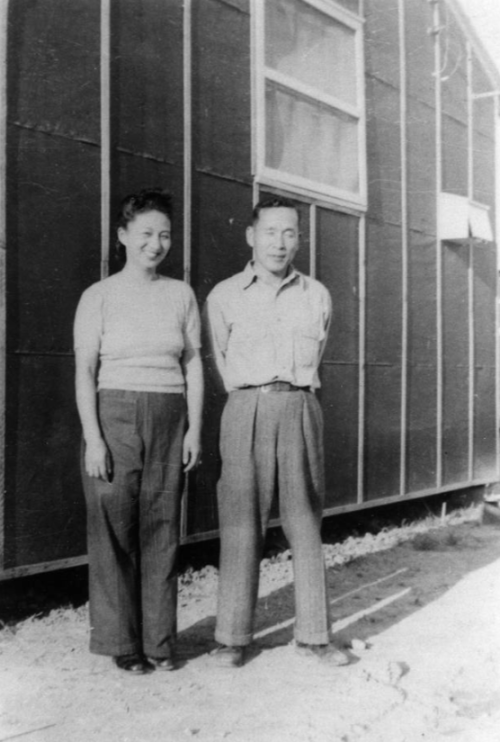

After graduating from Fresno High School, Henmi briefly enrolled at Fresno State Normal School (now California State University, Fresno). But the Japanese attack on the US Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on December 7, 1941, changed the course of his life. After Pearl Harbor, the United States entered World War II, declaring war on the Axis Powers, which included Japan, Germany, Italy, and other countries. In 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which forced Japanese Americans to leave their homes and live in internment camps. The Henmis and other families like them were forced to sell their homes and businesses. Richard’s parents sold their grocery store at a financial loss. He remembered, “We could only take what we could carry. Pets, cars, houses … all those things we had to get rid of. After a week, we were put into military buses and were taken over to a temporary evacuation center.”

The Henmis were transported to the same Fresno County fairgrounds where Richard had once won awards for his model airplane designs. Barbed wire and guards kept them from leaving. “Ironically, this became our concentration center,” Richard later said. “They had built wooden tar-paper shacks, buildings. Each building had six units, enough for six families. Each family had a space that was 20 x 20 [feet]. One lightbulb in the space, two windows, one door . . . You had to hang sheets to separate men and women. Toilets and showers were in a single building and some were 200 feet away from where you lived.” Eventually, Soichi, Helen, and Edward were sent to a camp in Jerome, Arkansas, where they remained until the US Supreme Court ruled that the camps were unconstitutional in 1944.

A New Life in Missouri

Richard Henmi, however, was not sent to the camp with his family. Instead, thanks to a higher education policy that allowed Japanese American students to attend colleges in the United States instead of going to the camps, Henmi joined dozens of students enrolling at Missouri colleges and universities. Although he had wanted to study aeronautical engineering, Henmi instead chose architecture at Washington University in St. Louis. His fellow Japanese American classmates there included his childhood friend Ted Ono as well as Gyo Obata, who, like him, would become a well-known architect.

Richard was soon joined by the rest of his family in St. Louis. Their move was aided by Luella Sayman, a civic leader and the widow of successful St. Louis businessman Thomas M. Sayman. Living in an apartment in Sayman’s carriage house, Soichi worked for Sayman as a chauffeur and gardener while Helen worked as a seamstress. Richard’s younger brother Edward enrolled at Soldan High School. During this time, Richard met and married Toyoko Hidekawa. Originally from San Francisco, California, Toyoko had recently moved to St. Louis after being released from an internment camp in Utah. Richard and Toyoko were married until her death in 1989.

World War II

In 1943, while still a student at Washington University, Richard was drafted into the US Army. However, due to restrictions on Japanese American soldiers serving in the military, he was enrolled in the army reserves before he was put on active duty. After graduating from Soldan, his brother Edward served in Europe with the 442nd Infantry Regiment. That segregated all-Japanese American unit remains the most decorated in US military history. Although Richard was still in training when World War II concluded in 1945, he completed officer candidate school and was commissioned as a second lieutenant. He served in the military police in Europe just after the war ended and was responsible for transporting German prisoners-of-war back to Germany. Upon being honorably discharged from the military, Richard returned to Washington University and completed a bachelor’s degree in architecture in 1947.

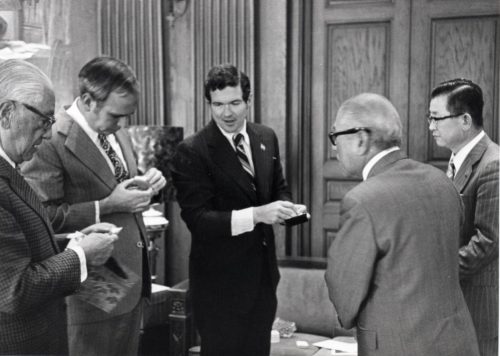

Japanese American Citizens League

Following World War II, the Japanese American population of St. Louis was estimated to be roughly 450, many of whom had moved to the city after being released from internment camps or had stayed following graduation from local colleges. Later in life, Henmi reflected that he and other Japanese Americans stayed in St. Louis “because the opportunities are better here, and because there is less prejudice here—definitely a friendly feeling.” Attempting to develop a sense of community and address the concerns of Japanese American residents of the city, Henmi was actively involved in the St. Louis chapter of the Japanese American Citizens League, an organization founded in 1929 and dedicated to cultural heritage, civic engagement, and civil rights.

He and the League later played an important part in creating a traditional Japanese garden at the Missouri Botanical Garden in St. Louis. Named Seiwa-en, the garden was designed by Koichi Kawana and officially dedicated in 1977. Encompassing fourteen acres, Seiwa-en is one of the largest Japanese gardens in North America.

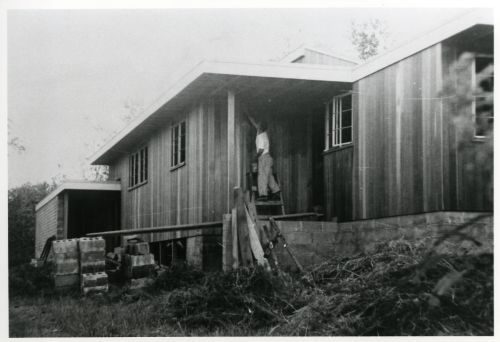

Redesigning the St. Louis Skyline

In 1951, Henmi was hired by the St. Louis architectural firm Russell, Mullgardt, Schwarz and Van Hoefen. Starting out as a designer, Henmi rose through the firm and became a partner, a high-ranking leadership position, of the newly named Schwarz and Henmi firm in 1969. At the time of his retirement in 1989, the firm was known as Henmi & Associates. In an interview about his life and career, Henmi said, “The people you deal with, work with, learn with, study with treat you pretty much the same way you treat them. The way you deal with them has a lot to do with how happy your life can be.”

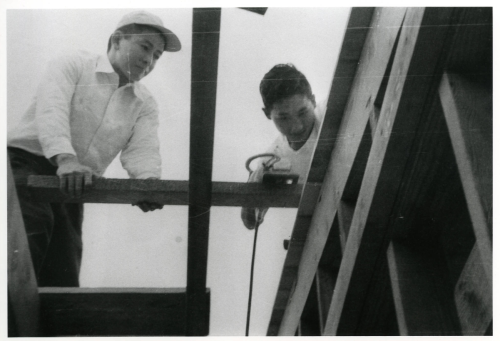

While Henmi designed countless buildings around the United States, some of his most famous designs were built in St. Louis. Inspired by the construction of the Gateway Arch, Henmi designed Mansion House Center, a series of apartment towers overlooking the famous monument, in 1966. A few years later, he helped design a hotel tower on top of the Spanish International Pavilion, a structure originally created for the 1964 New York World’s Fair and famously moved to St. Louis by Mayor Alfonso Cervantes as a tourist attraction. Perhaps Henmi’s most famous design was a Phillips 66 gas station built in 1967 near the campus of Saint Louis University that was known as the “flying saucer” for its unique circular roof. In 2012, St. Louisans organized a historic preservation campaign to prevent its demolition, proving the building had cemented its legacy as a local landmark.

Legacy

Throughout his career, Richard Henmi was a member of the American Institute of Architects. Though his most famous buildings are in St. Louis, he also designed notable structures throughout Missouri, particularly several at Lincoln University in Jefferson City, including Dwight T. Reed Stadium.

In 2003 he received the distinguished alumni award from Washington University’s College of Architecture. A decade later, Missouri Preservation, a statewide nonprofit organization, gave a Preserve Missouri Award to the efforts to preserve the “flying saucer.” Richard Henmi died in Webster Groves, Missouri, on July 7, 2020.

Text and research by Sean Rost

References and Resources

For more information about Richard Henmi’s life and career, see the following resources:

Society Resources

The following is a selected list of books, articles, and manuscripts about Richard Henmi in the research centers of The State Historical Society of Missouri. The Society’s call numbers follow the citations in brackets.

Articles from the Newspaper Collection

- “3 New Associates Named to St. Louis Architectural Firm.” St. Louis Globe-Democrat. September 9, 1956. p. 4C.

- “30 American-born Japanese Students from West Coast in Colleges Here.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. October 27, 1942. p. 3A.

- “Architects Change Firm Name.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. April 24, 1960. p. 4-J.

- “Architectural Firm Changes Name.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. January 5, 1969. p. 2-I.

- Holleman, Joe. “Architect known for the ‘Flying Saucer’ and Mansion House Center Dies at 96.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. July 16, 2020. p. A2.

- “Japanese Americans Call St. Louis a Friendly Haven.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. January 26, 1956. p. 11A.

- Leonard, Mary Delach. “A Legacy of Distrust.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. March 24, 2002. pp. A1, A13.

- McCue, George. “High-Rise Design for Riverfront.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. March 13, 1960. p. 5C.

- “Richard T. Henmi, AIA Named as Partner of Schwartz & Van Hoefen.” Webster Advertiser. February 29, 1968. p. 6.

- Terry, Dickson. “Japanese Moon over St. Louis.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. October 22, 1961. p. 1K.

- “Work Beginning on New Stadium.” The Lincoln Clarion. March 13, 1970. pp. 1, 4.

- Washington University. The Hatchet. St. Louis: Washington University, 1944. [REF 378.778W2 V9 1944]

- Washington University. The Hatchet. St. Louis: Washington University, 1945. [REF 378.778W2 V9 1945]

- Oral Histories of the Japanese American Community in St. Louis Collection (S0682)

The Oral Histories of the Japanese American Community in St. Louis Collection documents the experiences of Japanese Americans during and after their time in internment camps. It includes tapes and transcripts of the oral history interviews conducted as part of Herm Smith’s documentation project, which began in 1984. The collection also includes the records of the St. Louis Chapter of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), which Smith collected during the project. The JACL materials date from the 1950s to the 1970s and consist of newsletters, newspaper clippings, financial ledgers, meeting minutes, and correspondence that documents the group’s efforts to protect the civil rights of Japanese Americans.

Outside Resources

These links will take you outside the Society’s website. The Society is not responsible for the content of the following websites:

- A Song of Resilience

This website is hosted by ArcGIS/Washington University and includes interactive materials related to the experiences of Japanese Americans, particularly architects Richard Henmi and Gyo Obata, in St. Louis. - St. Louis Public Radio

This website is hosted by St. Louis Public Radio and features a news story about Richard Henmi’s life and career. - Webster-Kirkwood Times

This website is hosted by Webster-Kirkwood Times and features an article about Richard Henmi’s life and career.