Sacred Sun

Introduction

Sacred Sun, also known as Mohongo, was a courageous Osage woman who lived for some time on Osage land in present-day Missouri. Sacred Sun took a remarkable journey to Europe. Her adventure was recorded in French and American newspapers and pamphlets of the day. When she returned to America, her portrait was painted and displayed in Washington, D.C.

Early Years

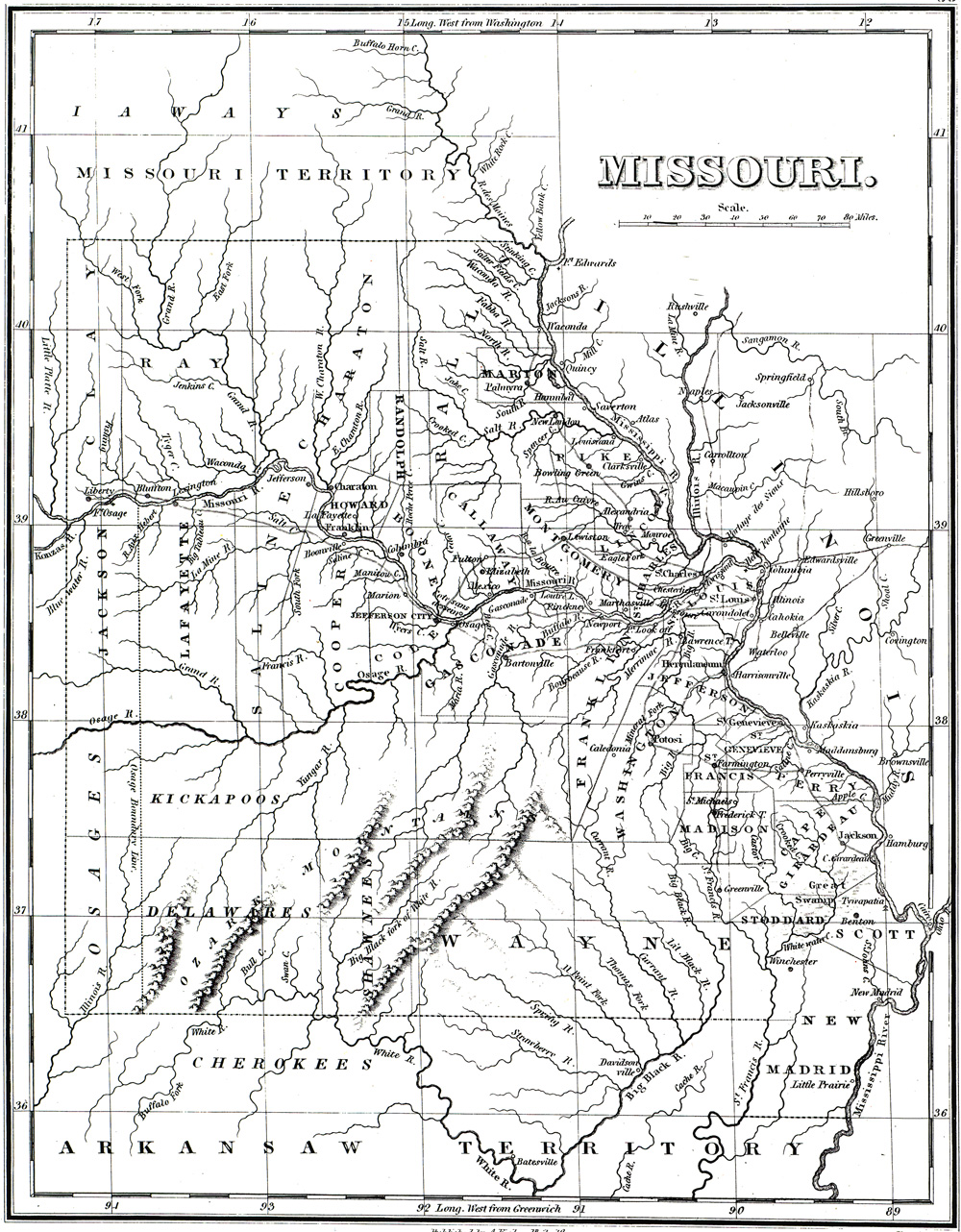

Sacred Sun was probably born around 1809 in an Osage village on the Missouri River, perhaps in what is now Saline County. Mi-Ho’n-Ga was her Native American name. The Osage were nomadic hunters, who also spent periods of time in their villages. As a baby, Sacred Sun would have been strapped to a cradleboard and fastened to a tree branch while her mother worked with other Osage women tending gardens, preserving meat, sewing clothes, and making domestic tools and vessels.

Because the Osage had been trading furs with the French for European goods for nearly a century, Sacred Sun would have been in close contact with French fur traders. She may have even been the country wife of a French fur trader. Sacred Sun would have seen American settlers steadily move into Osage territory. Since the United States had purchased the land west of the Mississippi in 1803, her tribal homeland had become sprinkled with forts, trading posts, and pioneer homesteads. With the coming of settlers and the United States Army, traditional life for the Osage people changed dramatically. By the time Sacred Sun was twelve or thirteen, she would have heard about, or experienced, many hardships due to war, starvation, disease, and the relocation of her people and other indigenous tribes.

The Osage

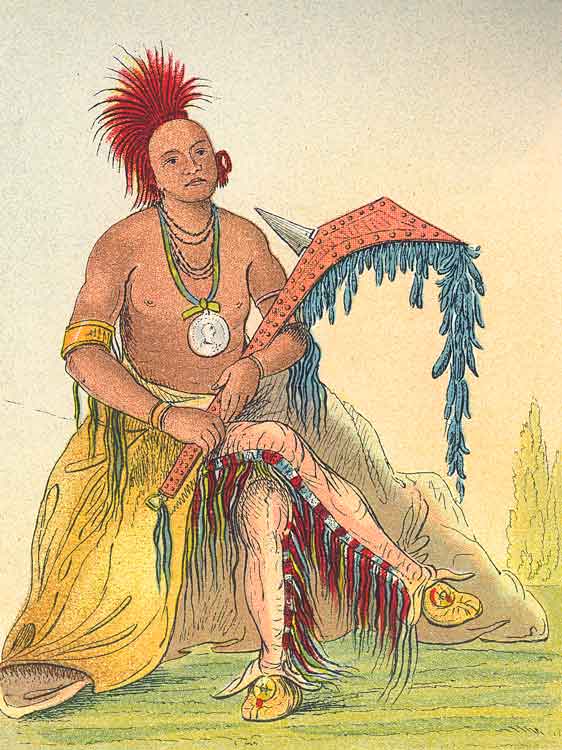

When the first French explorers came to present-day Missouri, they found two indigenous tribes, the Osage and the Missouri. The Osage tribe was the largest and most powerful group in Missouri at one time. Early in their history, the Osage divided into two groups: the “Upper-Forest Sitters” and the “Down-Below People.” French missionaries later called them the Great or Big Osage and the Little Osage, respectively. The Big Osage lived along the Osage River in present-day Vernon County, and the Little Osage lived along the Missouri River in what is today Saline County. Sacred Sun was a Little Osage.

[Wolferman, The Osage in Missouri, p.10, and McCandless and Foley, Missouri; Then and Now, p. 11.]

Sacred Sun’s Journey Begins

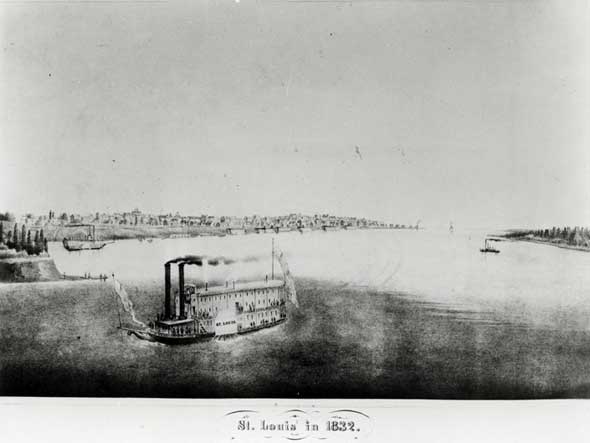

In 1827, eighteen-year-old Sacred Sun made plans to travel to France with eleven other people from her tribe. David Delaunay, a French-born resident of St. Louis organized the trip and would be their guide. Other Osage had taken trips to France and Washington, D.C. in the past. Though the exact reason for their trip is unknown, the Osage hunted game and prepared furs for four years to pay for their journey.

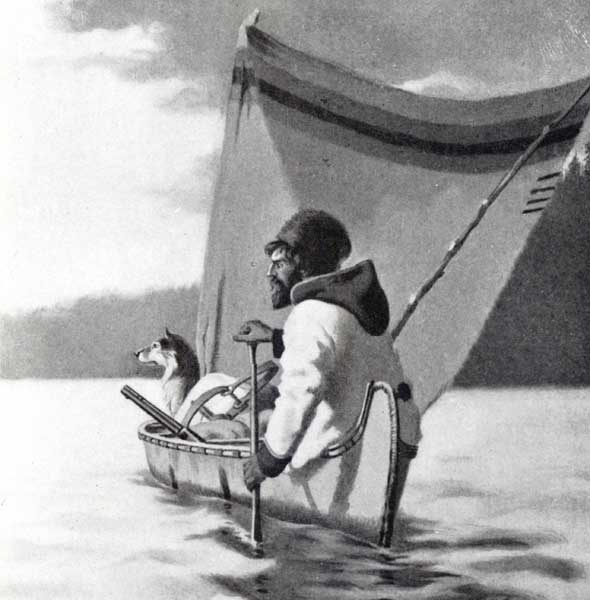

After loading their furs on a raft, the twelve Osage set off on the Missouri River for St. Louis. As they neared the city, the raft wrecked and all the furs were lost. Half of the Osage decided to return to their village while the other half —Sacred Sun (Mi-Ho’n-Ga), Little Chief (Ki-He-Kah Shinkah), Hawk Woman (Gthe-Do’n-Wi’n), Black Bird (Washinka Sabe), Big Soldier (Mo’n-Sho’n A-ki-Da Tonkah) and Minckchatahooh —continued. They soon joined Delaunay and his assistants and took a steamboat called Commerce down the Mississippi to New Orleans. There they boarded a ship named New England and set sail for France.

An Honored Guest in France

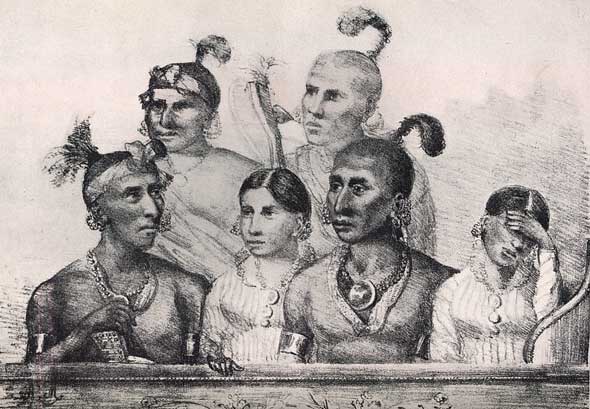

Sacred Sun arrived in Le Havre, France, on July 27, 1827. She was greeted by a crowd of excited French citizens. According to French newspaper descriptions and drawings, the six Osage looked exotic and interesting. Sacred Sun was particularly beautiful with her large, lively eyes and small frame. Both she and Hawk Woman wore their black hair in the traditional Osage fashion with it parted down the center with a red line painted down the parting. This red line represented the dawn road of Grandfather the Sun. Sacred Sun wore a red tunic over her knee-length dress, mitas—or gaiters—made of beaver skin over her shoes, and strands of shells around her neck.

At first, Sacred Sun and her group were treated well by the French. They stayed in nice hotels, ate rich food, and rode in carriages to attend operas and other places of interest. They met King Charles X at his palace in St. Cloud. Before long, however, the French lost interest, and David Delaunay found it difficult to feed and afford lodging for the Osage. He tried various ways to raise money. He sold tickets to see them in their hotel rooms. He arranged an event at which the Osage agreed to perform their native dances, and Little Chief went up in a hot air balloon. Eventually, however, Delaunay ran out of money.

Sacred Sun’s Hardships

Meanwhile, Sacred Sun had another important matter facing her. She was pregnant and wanted to return home to deliver her baby in the safety of her tribal village. Newspapers reported that she wept in public. On February 10, 1828, about six months after arriving in France, Sacred Sun gave birth to twin daughters in a hotel in Belgium. Both girls were given French names, Maria Theresa Ludovica Clementina Black Bird and Maria Elizabeth Josepha Julia Carola. For unknown reasons, Sacred Sun let a wealthy Belgian woman adopt one daughter, Maria Theresa, while she kept the other, Maria Elizabeth. Sacred Sun and Maria Elizabeth are pictured in a portrait painted by Charles Bird King.

Around the same time, Delaunay was imprisoned for not paying his bills. The Osages were left to survive on their own.

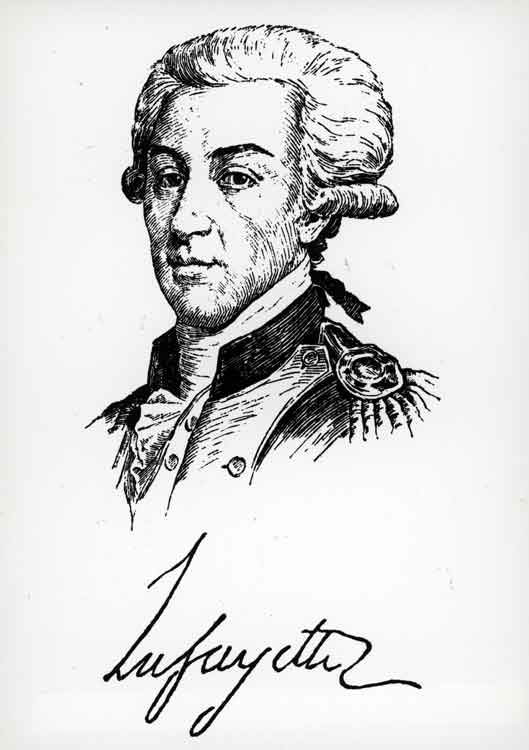

Sacred Sun and the other unhappy Osages spent the next two years traveling in Europe, trying to survive and find a way home. They begged for food and lodging. Eventually, a newspaper wrote about their dire situation. The Marquis de Lafayette, the French hero of the American Revolutionary War, sent Sacred Sun, her baby, Black Bird, and Minckchatahooh back to America. Sacred Sun and one of her daughters arrived safely at Norfolk, Virginia, in late 1829, but Black Bird and Minckchatahooh supposedly died of smallpox aboard the ship. Little Chief, Hawk Woman, and Big Soldier returned to America a few months later. The Osage were reunited in Washington, D.C.

Back in America

Thomas L. McKenney, director of the Bureau of Indian Affairs from 1824 to 1830, had the artist Charles Bird King paint a portrait of Sacred Sun and her baby while she was in Washington, D.C. The portrait hung in the National Indian Portrait Gallery until 1865 when it was destroyed by fire. Copies of all the portraits in the gallery, including Sacred Sun’s, had been made before the fire. They were printed in the book History of the Indian Tribes of North America.

Sacred Sun’s Legacy

Sacred Sun was an adventurous and brave woman who lived during a period of great change for her people, the Osage. Her portrait and the accounts of her ambitious journey to Europe offer a glimpse of her life and personality. When Sacred Sun returned to St. Louis in the summer of 1830, she traveled to rejoin her tribe—no longer in Missouri, but living in the Oklahoma Territory near Fort Gibson—and there she lived probably another six years on land set aside for the Osage.

Text by Carlynn Trout with research assistance by Bridget Begley

References and Resources

For more information about Sacred Sun’s life and career, see the following resources:

Society Resources

The following is a selected list of books, articles, and manuscripts about Sacred Sun in the research centers of The State Historical Society of Missouri. The Society’s call numbers follow the citations in brackets.

Articles from the Missouri Historical Review

- McMillen, Margot Ford. “Les Indiens Osages: French Publicity for the Traveling Osage.” v. 97, no. 4 (July 2003), pp. 295-333.

- Shoemaker, Floyd C., ed. “Missouriana–Mohongo’s Story.” v. 36, no. 2 (January 1942), pp. 210-214.

Articles from the Newspaper Collection

- “Osage in France.” The Missouri Republican. November 1, 1827, p. 2. c. 4; November 8, 1827, p. 3. c. 2; November 14, 1827; p. 2, c. 1. [Reel # 41299]

- “Osage may visit Philadelphia.” The Missouri Republican. September 13, 1824, p. 2, c. 3. [Reel # 41297]

Books and Articles

- Barry, Louise.The Beginning of the West: Annals of the Kansas Gateway to the American West, 1540–1854. Topeka: Kansas State Historical Society, 1972. pp. 143-144. [REF 978.1 B279]

- Christensen, Lawrence O., William E. Foley, Gary R. Kremer, and Kenneth H. Winn, eds. Dictionary of Missouri Biography. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1999. pp. 67-68 (Big Soldier); 167-179 (Chouteau family). [REF F508 D561]

- Fletcher, Alice C. “The Osage Indians in France.” American Anthropologist. v. 2, no. 2 (April-June 1900), pp. 395-400. [REF Vertical File]

- Foreman, Carolyn Thomas. “Curiosity on the Continent.” Indians Abroad, 1493-1938. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1943. pp. 132-146. [REF 970.6 F761]

- Foreman, Grant. “Our Indian Ambassadors to Europe.” Missouri Historical Society Collections. v. 5, no. 2 (February 1928), pp. 109-128. [REF F550 M69 v.5]

- Hodge, Frederick Webb, ed. Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico. Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin 30. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1907. Part 1 (A-M): pp. 927-929 (Mohongo). Part 2, (N-Z): pp. 156-159 (Osage). [REF 572.05 Un3b no. 30]

- Mathews, John Joseph. “Little Chief and Hawk Woman Go to France.” The Osages: Children of the Middle Waters. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1961. pp. 539-547. [REF F580.3 M423]

- McCandless, Perry and William E. Foley. Missouri; Then and Now. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2001. [REF F550 M126m 2001]

- McKenney, Thomas L. and James Hall. “Mohongo (An Osage Woman).”The Indian Tribes of North America. Edinburgh, Scotland: John Grant, 1933. v. 1, pp. 44-49. [REF 970.1 M196 v. 1]

- McMillen, Margot Ford and Heather Roberson. Called to Courage: Four Missouri Women. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2002. pp. 5-33. [REF F508 M228]

- McMillen, Margot Ford and Heather Roberson. Into the Spotlight: Four Missouri Women. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2004. pp. 1–34. [F508 M228in]

- Trout, Carlynn. Notable Women of Missouri. Columbia, MO: Columbia: American Association of University Women–Columbia, Missouri Branch, 2005. pp. 3–4. [F508 T758 2005]

- Wolferman, Kristie C. The Osage in Missouri. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1997. [F580.3 W832]

Manuscript Collection

- John Dougherty Letter Book, 1826-1829 (C2292)

The Dougherty letter book contains letters from John Dougherty, a fur trader, interpreter, and Upper Missouri Indian agent, to William Clark, superintendent of Indian affairs at St. Louis, various U.S. Army officers, Indian agents, interpreters and fur traders, U.S. War and Treasury Department officials, Missouri politicians, and private citizens. Information about the Osage Indians can be found throughout the book. - “Southwestern Missouri Indians,” Roy Godsey, n.d. (C2089)

Manuscript submitted to the Missouri Historical Review about southwestern Missouri’s Native American population, especially the Osage.

Outside Resources

These links, which open in another window, will take you outside the Society’s website. The Society is not responsible for the content of the following websites:

- The Lewis and Clark Journey of Discovery

This website presents information on the Osage Indians recorded by members of the Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1804. - McKenney-Hall Collection

This digital collection at the University of Washington features the text and hand-colored lithographs from The History of the Indian Tribes of North America by Thomas L. McKenney and James Hall. - The Osage

This website provides some history on the Osage with a link to Osage hunting. - Osage Nation

The official website of the Osage Nation includes information, videos, photographs, and podcasts about Osage food, language, and culture.