Scott Joplin

Introduction

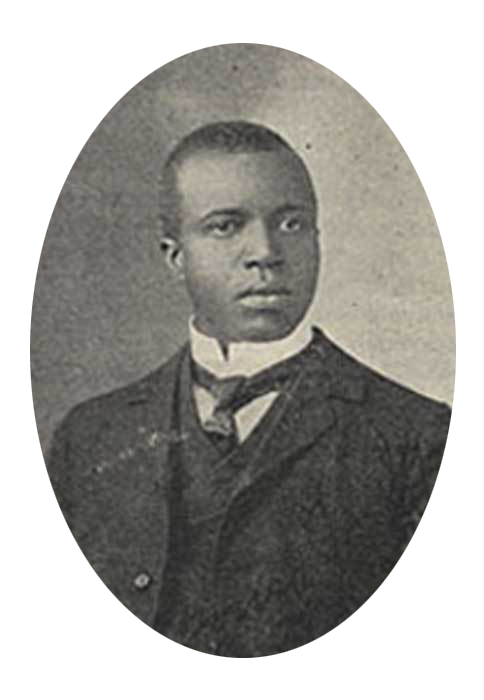

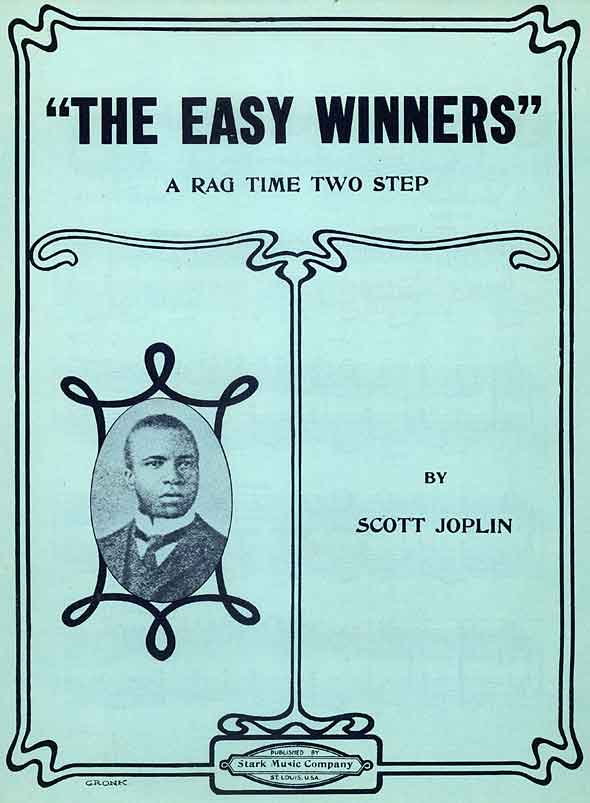

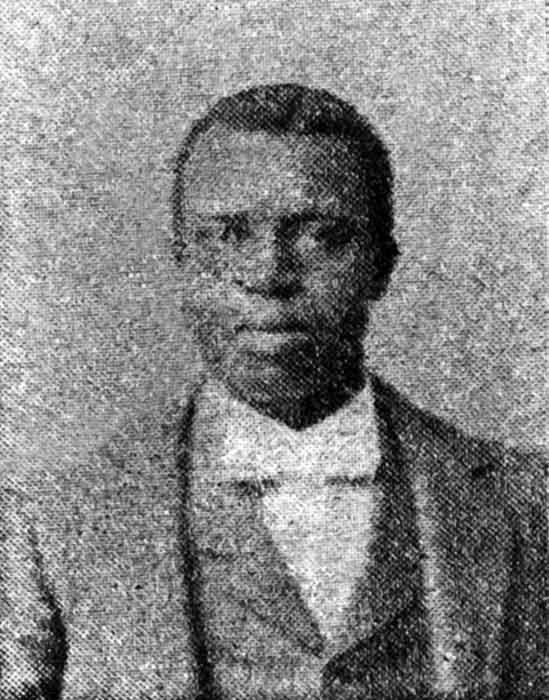

Scott Joplin was a musician and composer. He is considered the “King of Ragtime Writers.” Ragtime is music played in “ragged” or off-the-beat time. This varied rhythm developed from African American work songs, gospel tunes, and dance. Joplin wrote forty-four original piano pieces or rags, two operas, and one ragtime ballet. He also co-wrote seven rags with other composers.

Early Years

Scott Joplin was born around 1868 in northeastern Texas. He was the second of six children born to Giles and Florence Joplin. His family lived for a while on the farm of William Caves, but moved to Texarkana, Texas, in the 1870s. His father worked as a laborer, and his mother was a house cleaner and laundress. Joplin learned to play piano at an early age on the piano of his mother’s employer. He also took lessons from a German-born music teacher named Julius Weiss. Joplin’s parents were both very musical. His father played the violin, and his mother sang and played the banjo.

Joplin began performing as a musician when he was a teenager. In addition to the piano, Joplin played the violin and cornet. He also sang well. Sometime in the 1880s, Joplin left Texarkana and traveled to many places. He probably spent time in Sedalia, Missouri, attending Lincoln High School. He also went to St. Louis where he met Tom Turpin, another ragtime musician. Joplin played a variety of music, combining traditional western forms such as the waltz and march with melodies and rhythms borrowed from African American songs.

In 1893 Joplin traveled to Chicago at the time of the World’s Fair. He led and played the cornet in a band that played outside the fairgrounds. There he met musician Otis Saunders, who encouraged him to write down and publish the songs he had been making up as he entertained his audiences.

Music Training in Sedalia

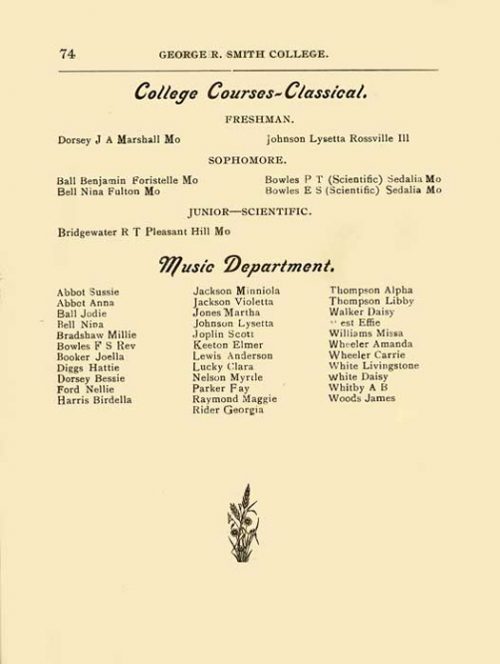

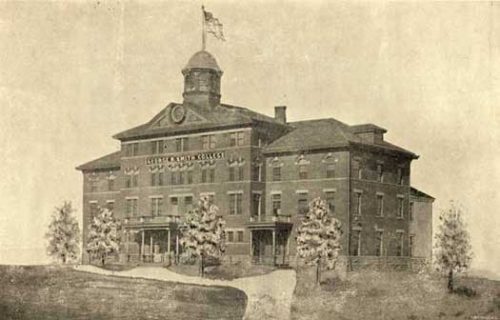

Scott Joplin moved to Sedalia, a busy railroad town in Missouri, in 1894. Here Joplin joined the Queen City Cornet Band and performed in local clubs. Using Sedalia as a home base, he continued to travel around the country with various musical groups. In 1896 he enrolled at the George R. Smith College to study music seriously and to develop the skill of transferring musical sounds into notes recorded on a page that other musicians could then play.

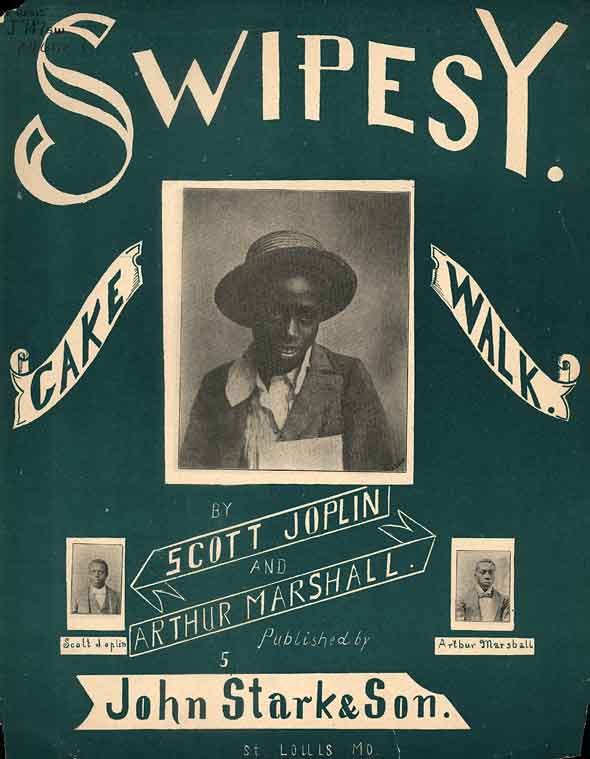

Joplin quickly learned how to write down the vibrant melodies and complex rhythms he and his fellow musicians had been developing. He then published several original compositions and also started co-writing songs with Sedalia musicians Arthur Marshall and Scott Hayden.

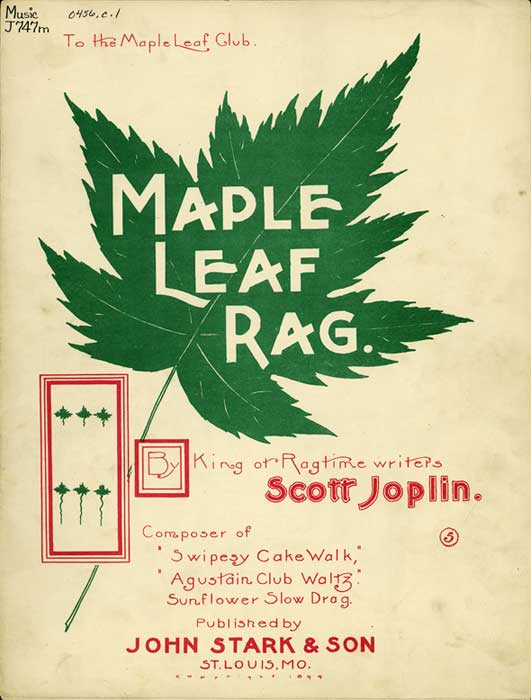

Scott Joplin soon became a popular and respected musician in Sedalia. In 1899, a local music store owner and music publisher named John Stark printed Joplin’s song “Maple Leaf Rag.” Immediately popular, this song featured a pleasing melody and a catchy beat. It became a classic model of ragtime music and thrust Joplin into the national spotlight. Eventually, this rag and many others earned Joplin the title “King of Ragtime Writers.”

High Hopes in St. Louis

Trying to build on the success of “Maple Leaf Rag,” Scott Joplin and his bride, Belle Jones, moved to St. Louis in 1901. John Stark had already moved there, and Hayden and Marshall came, too. Joplin and his friends hoped to become successful performers and composers in this urban center. With their presence, St. Louis became a focal point for this special kind of music.

Joplin devoted most of his time and energy to composing new pieces and teaching music lessons. He wrote and published many new works, including an opera and ballet, while living in St. Louis. His ragtime compositions gained the attention of classically trained musicians and critics. Alfred Ernst, conductor of the St. Louis Choral Symphony Society, described Joplin as “an extraordinary genius.” Monroe Rosenfield, a respected music critic for the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, praised Joplin’s work highly.

Despite this respect and his popularity, Joplin was like many other African American musicians of that time period. He was praised, but not fully included in white society. He performed places where other members of his race had limited access. Though Joplin’s popular rags were published, he had trouble raising money to produce the works that he cared most deeply about—his longer and more complicated compositions.

Scott Joplin’s private life also became troubled. He suffered the loss of an infant child, his first marriage ended, and his second wife, Freddie Alexander, died shortly after they were married in 1904. By late 1907, Joplin had left St. Louis and moved to New York City. He hoped that this city would offer him new opportunities and the solid financial backing he needed to continue his work.

Ragtime in New York City

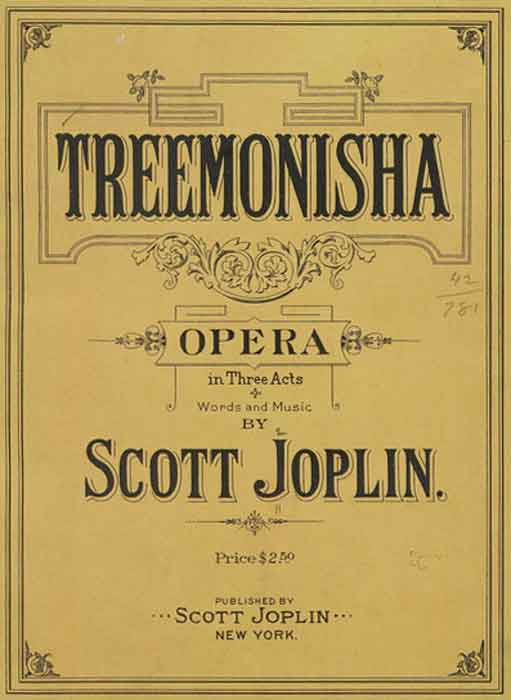

New York City offered Scott Joplin new experiences. Here he performed in vaudeville shows and wrote new songs. John Stark also moved to the city and set up his publishing business in a district called Tin Pan Alley. Joplin maintained his relationship with Stark, but also branched out with other publishers. He married again, this time to Lottie Stokes, who supported his work and efforts. Joplin still worked very hard for very little pay. He toiled for years on a major piece, a second opera titled Treemonisha.

Between 1911 and 1915, he put on a series of unstaged run-throughs and partial performances of Treemonisha, but the opera failed to gain financial backing for a full production. By this time, Joplin was suffering from a disease that made it difficult for him to compose and perform as he always had. Sick, discouraged, and poor, Scott Joplin died on April 1, 1917. He is buried in Saint Michael’s Cemetery in New York City.

Joplin's Legacy

Scott Joplin played an essential role in the development of ragtime music. His work also laid the groundwork for jazz, another distinctly American musical form. Through his performances and compositions, Joplin gave the world a unique form of music that combines classical structures and techniques with African American melodies and rhythms. He also opened the door for other black musicians and artists to succeed in a racially segregated nation.

Today, museums preserve Joplin’s memory and educate people about his contributions. His work was revived in the 1940s and more fully explored and promoted in the 1970s. A 1973 movie, The Sting, made his song “The Entertainer” a popular hit. His opera Treemonisha was finally fully produced, and in 1976 the Pulitzer Committee awarded Joplin a special Bicentennial Pulitzer Prize for his contribution to American music. Sedalia, Missouri, calls itself “The Cradle of Ragtime” and honors Joplin’s life and work with its annual “Scott Joplin Ragtime Music Festival.” Fans from around the world attend the festival to honor this great musician.

A Selection of Scott Joplin's Music

Text by Carlynn Trout with research assistance by Bridget Begley and Jillian Hartke

References and Resources

For more information about Scott Joplin’s life and career, see the following resources:

Society Resources

The following is a selected list of books, articles, and manuscripts about Scott Joplin in the research centers of The State Historical Society of Missouri. The Society’s call numbers follow the citations in brackets.

Articles from the Missouri Historical Review

- “Historical Notes and Comments.” Scott Joplin memorial monument erected in Sedalia. v. 56, no. 2 (January 1962), p. 192.

- “Missouri in 1898: Scott Joplin and the ‘Maple Leaf Rag. v. 92, no. 4 (July 1998), inside back cover.

- Taylor, John A. Book reviews of Dancing to A Black Man’s Tune: A Life of Scott Joplin, by Susan Curtis, and King of Ragtime: Scott Joplin and His Era, by Edward A. Berlin. v. 90, no. 3 (April 1996) pp. 384-386.

Articles from the Newspaper Collection

- Brockhoff, Dorothy. “Missouri Was the Birthplace of Ragtime.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. January 18, 1961. p. 3F. [Reel # 43110]

- Brown, Karen. “Celebrating Scott Joplin, Wrong Time Genius.” Kansas City Star. June 23, 1974. [Reel # 21866]

- Cochran, Kathy. “Great Scott.” Vibrations: Sunday Magazine of the Columbia Missourian. December 14, 1980. pp. 3-5. [Reel # 7827]

- “Did You Know Ragtime Music Was Born in Sedalia?” Sedalia Democrat. June 29, 1947. pp. 1, 6-7. [Reel # 47185]

- Hunter, Frank. “The Great Scott Joplin.” St. Louis Globe–Democrat. July 13-14, 1974. pp. 1, 3C. [Reel # 40739]

- “Most Famous Joplin Number Written Here.” Sedalia Democrat. June 28, 1990. p. 36B. [Reel # 47508]

- Ralston, James L. “Respectability for ‘King of Ragtime.’” Kansas City Times. June 8, 1972. [Reel # 21769]

- Rosenfeld, Monroe. “The King of Rag-Time Composers is Scott Joplin, a Colored St. Louisan,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat. June 7, 1903. Sporting Section, p. 5. [Reel # 39545]

- “St. Louis and Scott Joplin: Atlanta Revives Opera Composed Here by ‘King of Ragtime.’” An editorial reprinted from St. Louis American. St. Louis Post-Dispatch. February 2, 1972. p. 2E. [Reel # 43377]

- “To Play Ragtime in Europe.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. February 28, 1901. p. 3. [Reel # 41864]

Books and Articles

- Berlin, Edward A. King of Ragtime: Scott Joplin and His Era. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994. [REF F508.1 J747be]

- Blesh, Rudi, and Harriet Janis. They All Played Ragtime. rev. ed. New York: Oak Publications, 1966. [REF F565.3 B617]

- Bridges, Annette. “Scott Joplin House State Historic Site.” Missouri Resource Review. Summer 1992. pp. 28-30. [M339.49 M6912mrv]

- Christensen, Lawrence O., William E. Foley, Gary R. Kremer, and Kenneth H. Winn, eds. Dictionary of Missouri Biography. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1999. pp. 442-445. [REF F508 D561]

- Curtis, Susan. Dancing to a Black Man’s Tune: A Life of Scott Joplin. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1994. [REF F508.1 J747cu]

- Curtis, Susan. “Scott Joplin and Sedalia: The King of Ragtime in the Queen City of Missouri.” Gateway Heritage. Missouri Historical Society, Spring 1994. pp. 4-19. [F550 M69gh]

- Evans, Mark. Scott Joplin and the Ragtime Years. New York: Dodd, Mead, 1976. [IJ Ev16s]

- Haskins, James, with Kathleen Benson. Scott Joplin. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1978. [IJ Ev16s]

- Jennings, Ron. “Ragtime Struts Back Home.” Missouri Life. v. 2, no. 6 (Winter 1975), pp. 47-52. [F586 M6912]

- Mitchell, Barbara. Raggin’: A Story About Scott Joplin. Minneapolis: Carolrhoda Books, 1987. [IJ M692r]

- Southern, Eileen. The Music of Black Americans: A History. New York: W.W. Norton, 1971. [REF 780 So88]

Sheet Music

- Scott Joplin Sheet Music Collection [SHS Music J747]

Manuscript Collection

- Campbell, Sanford Brunson, Papers, 1947 (C3204)

Letters to Floyd C. Shoemaker, Columbia, MO, from Venice, CA, about ragtime musician Scott Joplin. Includes printed brochures regarding ragtime, jazz, and Scott Joplin. - Christeson, Robert P. (1911-1992), Collection, 1808-1995 (C3971)

This collection includes sheet music for six Joplin compositions: “The Favorite,” “Felicity Rag,” “Leola,” “Maple Leaf Rag,” “Palm Leaf Rag,” and “Stoptime Rag.”

Outside Resources

These links, which open in another window, will take you outside the Society’s website. The Society is not responsible for the content of the following websites:

- “Perfessor” Bill Edwards

This site is full of information about Scott Joplin and other ragtime musicians. - Scott Joplin

This website provides a biography of Joplin as well as a thorough explanation of ragtime music. - Scott Joplin House State Historic Site

This website provides photographs of the Joplin house in St. Louis and tourist information. - Scott Joplin Ragtime Festival

This site includes a detailed biography by Edward A. Berlin and information about the annual Ragtime Festival in Sedalia, Missouri.