Stanley Ketchel

Introduction

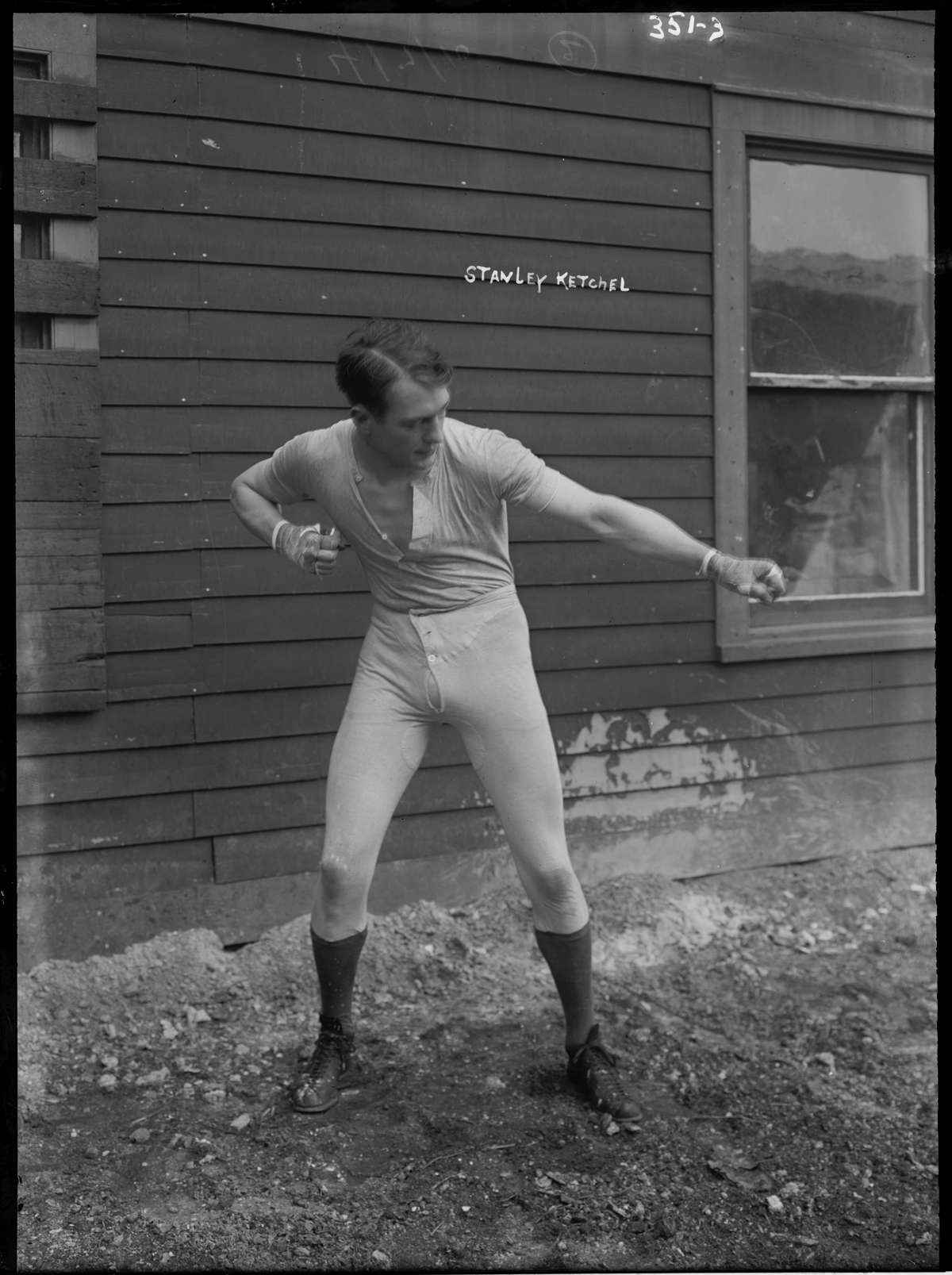

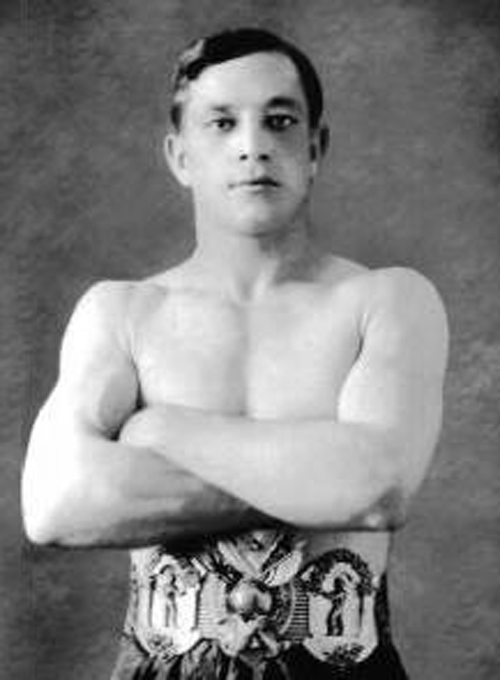

Some boxing experts argue Stanley Ketchel was the greatest middleweight boxer of all time. In his career, he won fifty-two of his sixty-four fights, forty-nine by knocking out his opponent. Ketchel fought four future members of the Boxing Hall of Fame, including Billy Papke, Philadelphia Jack O’Brien, Sam Langford and Jack Johnson, the heavyweight champion of the world. Johnson outweighed him significantly and was several inches taller. Ketchel failed to defeat Johnson, but planned to try again. While training on a Missouri ranch, Ketchel fell in love with the Ozarks and planned to start a business there, but his life was cut short. He was well-liked and handsome, and his murder stunned the people of southwest Missouri and the world.

Early Years

Stanislaus Kiecal was born in Belmont, Michigan, on September 14, 1886. He was the son of Thomas Kiecal and Julia Olbinski who had emigrated from Poland. Stanislaus ran away from home when he was fourteen years old and lived as a drifter for many years. He traveled from place to place by hiding in freight-train cars and did not settle anywhere until he arrived in Butte, Montana.

Montana

Stanislaus arrived in Butte around 1900. The frontier mining town had a reputation as being lawless. Business was booming, and the town’s many miners were ready to spend their money on drinking, gambling, and dance halls. Saloon hold-ups and murders were common occurrences.

Kiecal lived there during his teenage years and worked as a bouncer, a tough guy who forced drunks or other troublemakers to leave if they were bothering the rest of the crowd. He had a reputation as a brawler, and at age sixteen he began challenging locals to boxing matches. Lacking opponents in Butte, Kiecal traveled the state, challenging the best fighters in Montana. He had no formal training as a boxer, but of his forty-two professional fights in Montana, he only lost twice. Montana boxer Jerry McCarthy fought him during this period. “He is the strongest and gamest man I ever knew,” McCarthy said in 1908. “When he beat me in Great Falls (Montana) in 12 rounds I realized he was a wonder…I nailed him on the jaw with a hard right hander. Instead of stopping, he bored into me and hit me a million times…he knew nothing but fight and kept coming in.”

Middleweight Champion of the World

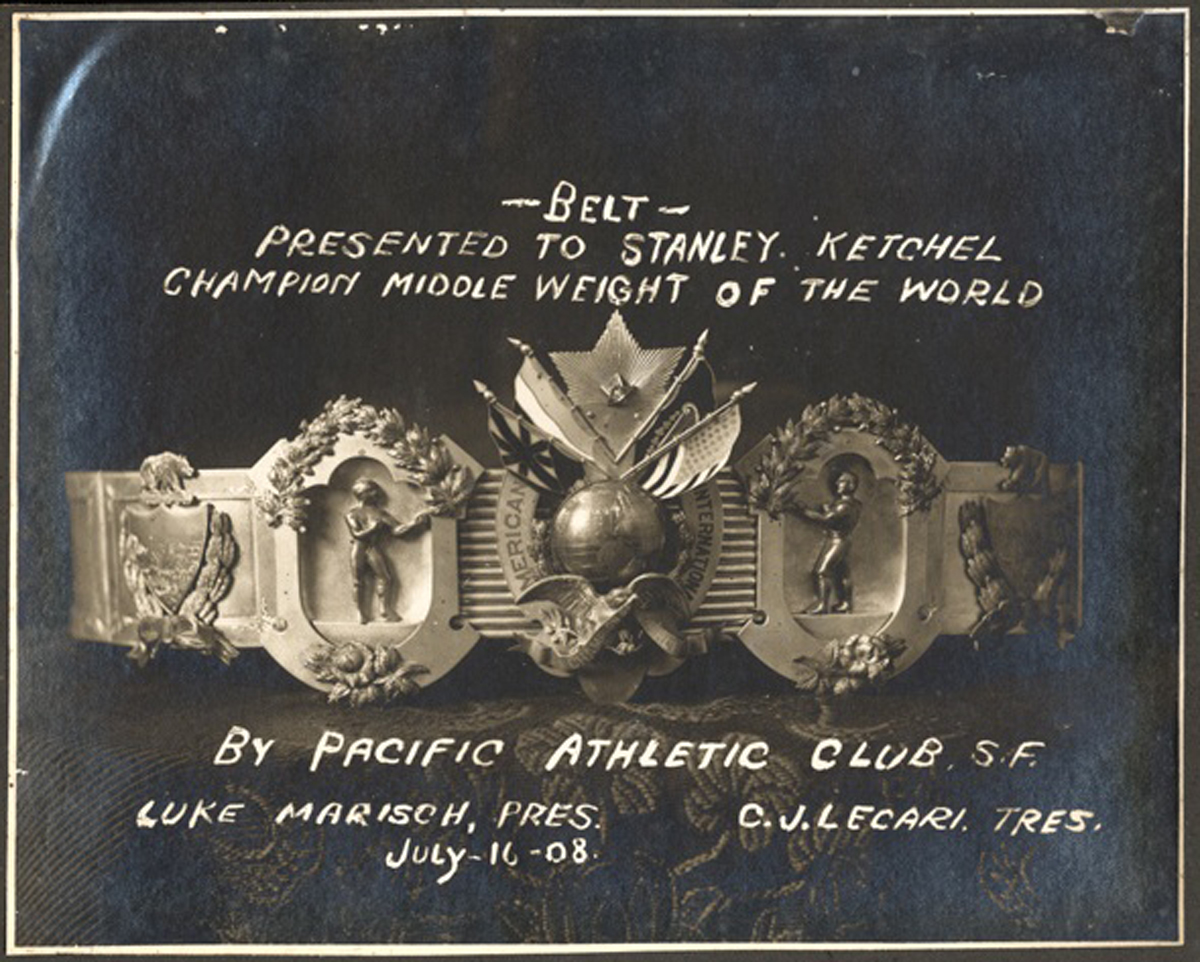

Stanislaus Americanized his name to Stanley Ketchel and moved to California to challenge higher-profile fighters. Although he faced more skilled opponents, he still seemed unstoppable, earning the nickname “The Michigan Assassin” because he won many of his fights so easily. His big break came in February 1908, when he fought Mike “Twin” Sullivan, a well-respected boxer. Ketchel knocked him out in the first round. He then fought Mike’s identical twin brother, Jack, for the middleweight championship belt. Ketchel fought Jack Sullivan in Colma, California, knocking him out in the twentieth round and winning the title.

In September 1908, Stanley briefly lost his champion’s belt to future Hall of Famer Billy Papke, largely because of an illegal punch delivered while the opponents shook hands before the first round. The referee did not penalize Papke, and Ketchel, dazed by the blow, never gained the upper hand and lost the bout. Six weeks later, on Thanksgiving Day, Ketchel retook the title from Papke and kept it until he died. He was the first middleweight to be a two-time champion.

Fight with Jack Johnson

Jack Johnson was the first African American to hold the title of heavyweight champion. Ketchel’s manager, Willus Britt, may have organized the fight between Johnson and Ketchel because so many hoped for a white man to take the title away from Johnson. Following a victory over light heavyweight champion Jack O’Brien in early 1909, Ketchel was feeling confident and agreed to the fight.

Johnson later said that Ketchel did not stand a chance of winning, but both knew they could make money from theaters replaying film of the contest, which they knew would only sell if the fight was entertaining. “I knew that Ketchel couldn’t hit me,” Johnson said, “and I knew that if I knocked him out in a hurry that moving picture houses wouldn’t buy a film of a negro beating a white man easily.” According to Johnson, his only goal was not to hurt Ketchel too much, and to keep the contest going.

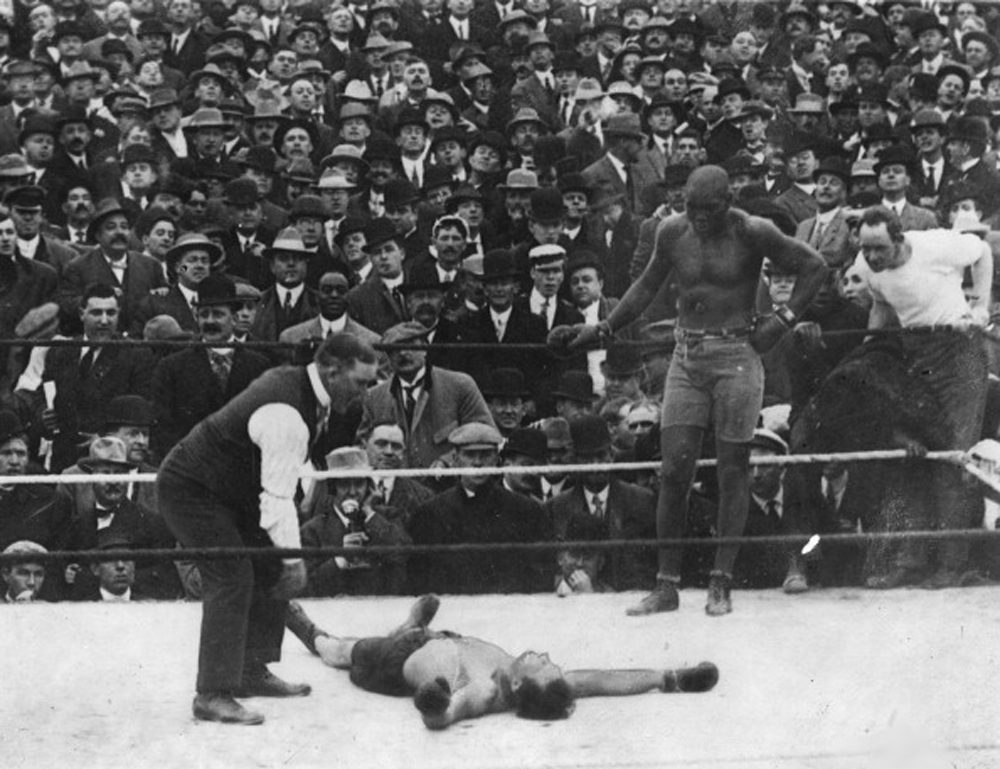

The fight took place on October 16, 1909. In the twelfth round, Ketchel knocked Jack Johnson down with a hard right-hand punch. Johnson said he exaggerated his fall and pretended to be groggy when he stood back up. Outside observers theorized that Ketchel had broken their agreement, enraging Johnson, who then hit Ketchel with his full strength. “I’ll never forget that sickening jolt,” Johnson later exaggerated, saying, “…when I hit him, he went right up in the air, turned a complete somersault, and landed on the back of his neck, out cold. The punch knocked out all of his front teeth.”

Ketchel could not eat anything but soup for three weeks. He told the Springfield Daily Leader, “If you think you know anything about pain, get in front of one of Jack Johnson’s knock-out blows and see if you don’t learn something new about how much a fellow can ache.” Johnson regretted hurting Ketchel. They were personal friends, and remained so. Both made a lot of money from the film of their fight, and the drama of the last round caused audiences to flock to see it. Debate about the legitimacy of this fight remains to this day.

Move to Missouri Ozarks

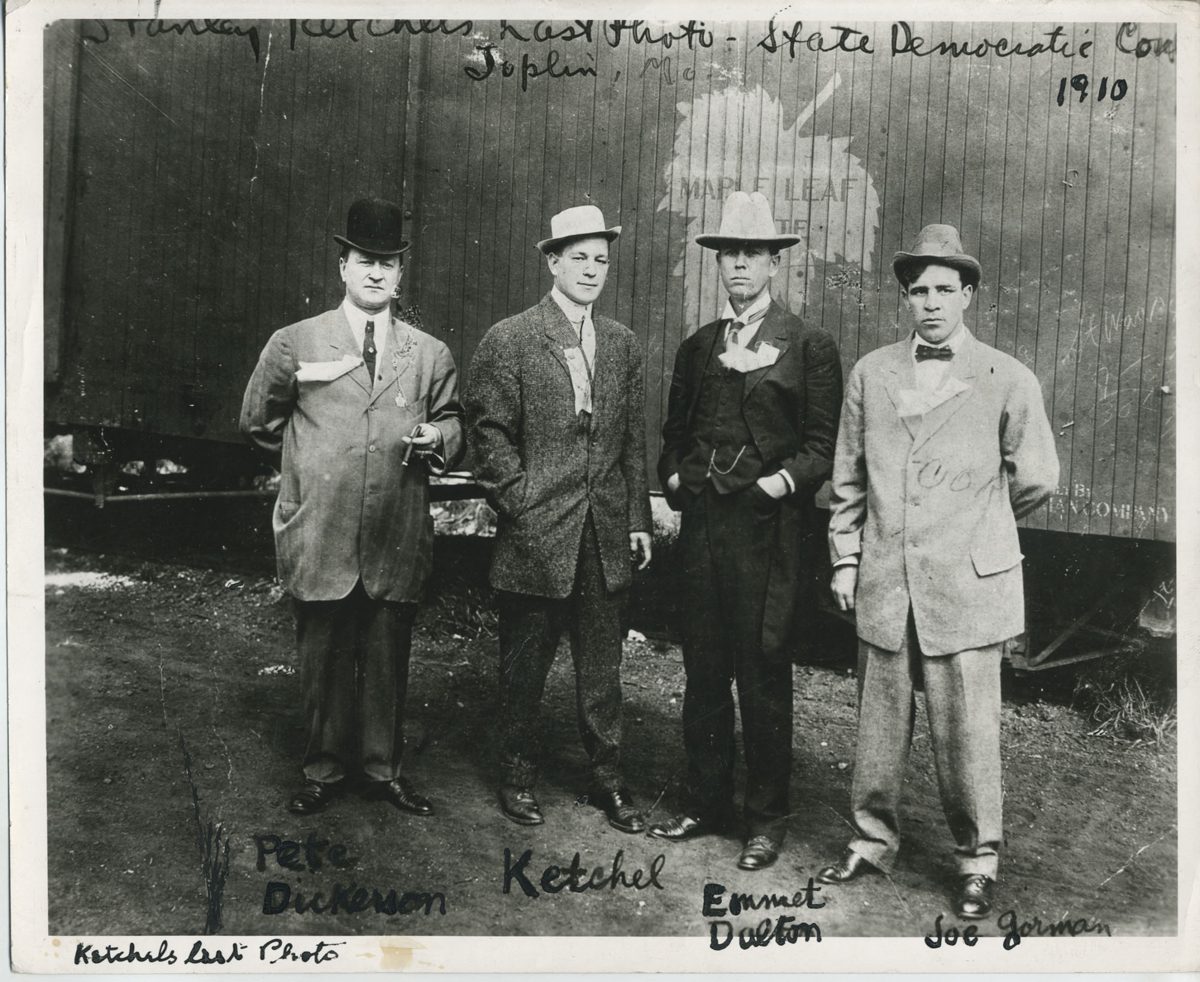

Ketchel needed several weeks to recover from the injuries to his jaw. His friend, Rollin P. Dickerson, invited him to stay at his 860-acre ranch in Conway, Missouri, while he trained to retake Johnson. Dickerson was a successful Springfield businessman who grew up in Michigan and was friends with Ketchel’s mother. When Ketchel arrived in Springfield on his twenty-fourth birthday, his presence caused great excitement. The Springfield Leader and Press reported, “Whenever Ketchel appears in the streets he is pointed out by those who know him by sight.” The paper reported that he was smaller than many expected and not intimidating: “he is a youngster of pleasing personality, courteous in manner and a good dresser.” Many were surprised by his youthful appearance.

Ketchel intended to begin immediate training for a rematch with Jack Johnson, but as Dickerson showed him around Springfield and the surrounding area, Ketchel decided to stay. He purchased 3,200 acres of timberland in Webster County, joined the newly formed Springfield Moose Lodge, joined the Elks Lodge, and watched footage of Jack Johnson fighting Jim Jeffries at the Lander’s Theater on Walnut Street. Dickerson and Ketchel planned to form a land company, Missouri Lumber and Land Company. Ketchel would serve as president and work from an office on Commercial Street in Springfield. To learn about business, Ketchel would manage Dickerson’s ranch in the meantime. He had been staying on the ranch since his arrival in September.

Death

On October 15, 1910, Goldie Smith, a woman Rollin P. Dickerson had hired to work as a cook, sat Stanley Ketchel down to breakfast with his back to the door. Ranch hand Walter Dipley, who claimed to be Goldie’s husband, came up behind Stanley and shot him in the back with a rifle. The bullet entered Stanley’s back just under his right shoulder blade and punctured his lung. Stanley died that evening at Springfield hospital after suffering for nearly twelve hours with internal bleeding and difficulty breathing and talking. “I guess they have got me,” he said repeatedly. Ketchel’s funeral at the Springfield Elk’s Lodge on October 18 was attended by ten thousand people before his body was shipped back to his parents in Michigan.

Murder Trial

Goldie Smith and Walter Dipley were charged with first-degree murder. Their trial was held in January 1911 in Marshfield. They claimed Stanley had assaulted Goldie the day before, and that Dipley killed him in self-defense. Other ranch employees thought robbery or an argument between Dipley and Stanley over Walter’s treatment of the ranch’s horses were more likely motives. Stanley often carried large amounts of cash and didn’t mind showing off his good fortune. When found, his pockets were empty, and he told Dickerson that the pair had taken his money. Walter and Goldie were convicted and sentenced to life in prison. Goldie was released on appeal, and Walter was paroled in 1934 after serving twenty-three years in prison.

Legacy

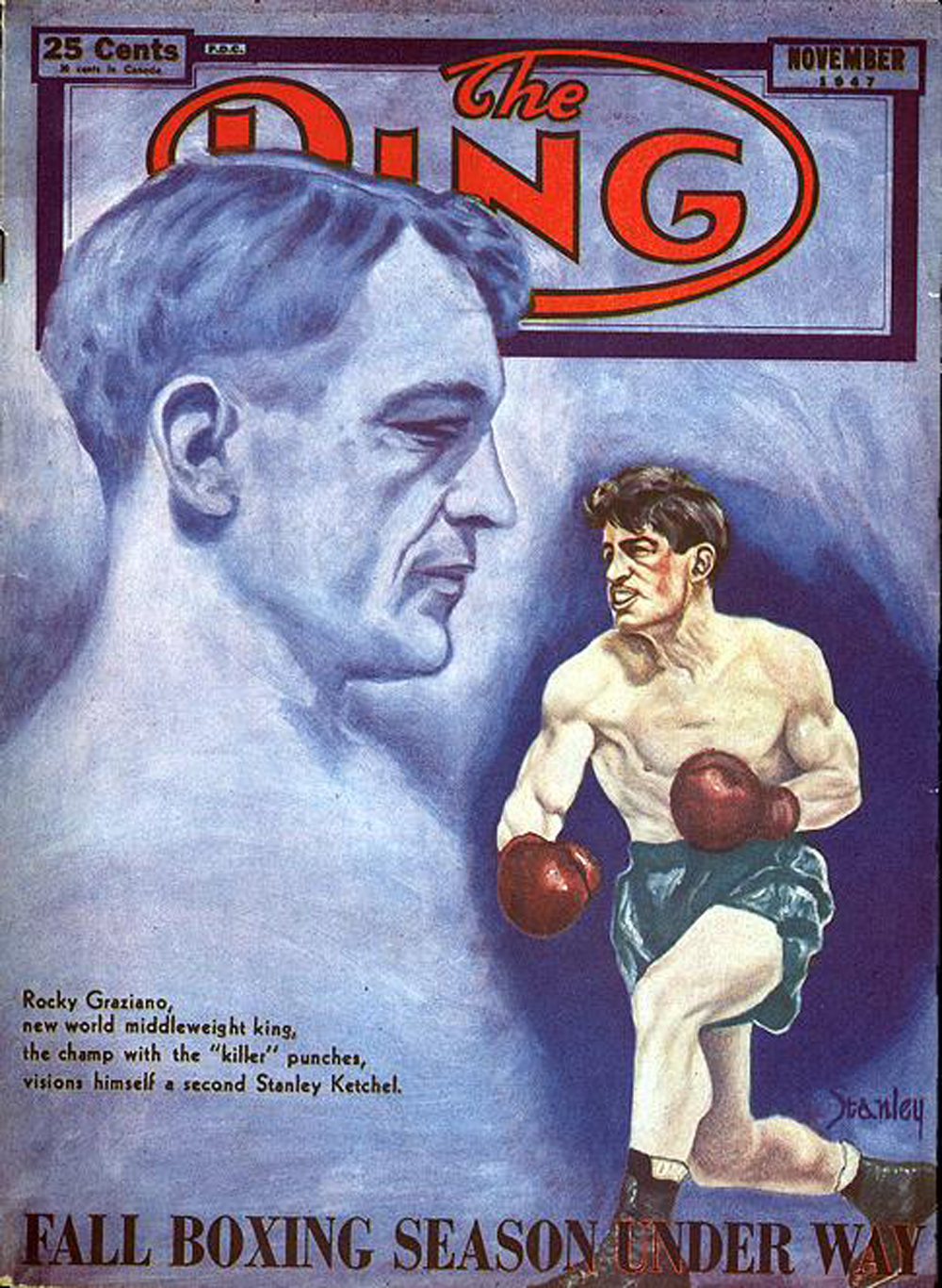

Nat Fleischman, editor of Ring Magazine, argued that Stanley Ketchel was the greatest middleweight boxer of all time. His career spanned only six years. In that time, he went from making twenty dollars a week fighting local challengers in bars in Butte, Montana, to gaining national fame as the two-time middleweight champion, and making thousands of dollars per fight.

Stanley Ketchel was inducted into the Boxing Hall of Fame in 1990. The life and business career he planned to have in Missouri was never to be. He did not get to run his timber business. He never built his Webster County home, and he did not develop the friendships and social life he had started in Springfield. He was remembered fondly by those who knew him, including his opponent Jack Johnson. Ketchel’s murder shocked the world, and his reputation for never giving up in a fight led his manager, Wilson Mizner, to reportedly mutter when hearing of his death, “Tell ‘em to count to ten over him and he’ll get up.”

Text and research by Erin Smither

References and Resources

For more information about Stanley Ketchel’s life and career, see the following resources:

Society Resources

The following is a selected list of books, articles, and manuscripts about Stanley Ketchel in the research centers of The State Historical Society of Missouri. The Society’s call numbers follow the citations in brackets.

Articles from the Newspaper Collection

- “10,000 Look on Face of Stanley Ketchel.” Springfield Missouri Republican. October 18, 1910. p. 3. [Reel # 50324]

- “England May See Next Big Fight.” The Springfield Leader. September 18, 1910. p. 5. [Reel # 48897]

- “Ketchel and Dickerson Organize Land Company.” Springfield Daily Leader. October 2, 1910. [Reel # 48897]

- “New Elks Are Initiated; One Is Pugilist.” Springfield Missouri Republican. October 7, 1910. p. 4. [Reel # 50324]

- “Pugilist Dies Shortly after His Arrival at Springfield Hospital.” The Springfield Leader October 16, 1910. p. 1. [Reel # 48897]

- “Pugilist to Have Fine Ozark Ranch Soon.” Springfield Missouri Republican. September 28, 1910. p. 4. [Reel # 50322]

- “Result of Fierce Punch on the Jaw.” Springfield Leader. October 3, 1910. p. 5. [Reel # 48897]

- “Stanley Ketchel Coming to Town.” Springfield Leader. September 14, 1910. p. 1. [Reel # 48897]

- “Stanley Ketchel Joins Local Order of Moose.” Springfield Leader. October 2, 1910. p. 5. [Reel # 48897]

- “Stanley Ketchel Shot.” Daily Democrat-Tribune. October 15, 1910. p. 1, c. 3. [Reel # 16317]

- “Young Ketchel Big Attraction in Springfield.” Springfield Leader. September 16, 1910. p. 1. [Reel # 48897]

Books and Articles

- Gilmore, Robert K. White River Journal: Radiobook. Springfield: Southwest Missouri State University Printing Service. pp. 102-113. [REF F86 G425w]

- Wood, Larry. Murder and Mayhem in Missouri. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2013. pp. 89-97. [REF F538 W85]

Outside Resources

These links, which open in another window, will take you outside the Society’s website. The Society is not responsible for the content of the following websites:

- BoxRec

A short biography on Stanley Ketchel can be found on this boxing records website. - Director’s Cut: ‘Down Great Purple Valleys,’ by John Lardner

This article is part of a series that looks back at classic sports journalism. John Lardner originally profiled Stanley Ketchel in True Magazine in 1954. Lardner’s article is included here with additional commentary. - Fleisher, Nat. “The Michigan Assassin”: The Saga of Stanley Ketchel, World’s Most Sensational Middleweight Champion. New York: C.J. O’Brien, Inc., 1946.

- International Boxing Hall of Fame

Stanley Ketchel’s biography on the Boxing Hall of Fame website can be found here. - Mora, Manuel A. Stanley Ketchel: A Life of Triumph and Prophecy. Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse, 2010.

- On This Day: Jack Johnson Fought Stanley Ketchel

This article analyzes the fight with Jack Johnson and links to footage of the fight on YouTube. - Paloolian, Mark. Brutality: The Tragic Story of Stanley Ketchel, the “Michigan Assassin.” Tuscon, AZ: Wheatmark, 2007.