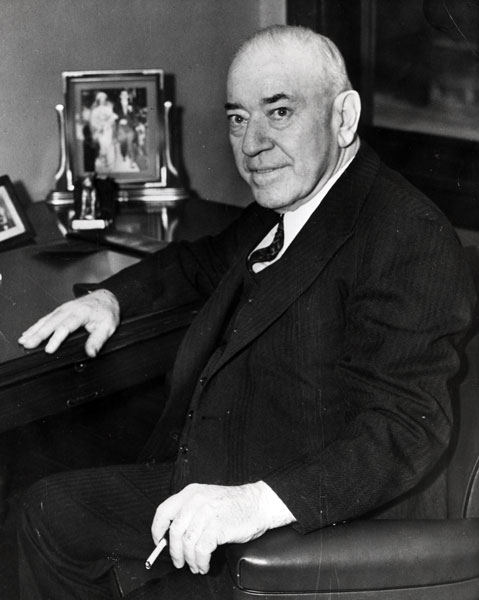

Thomas J. Pendergast

Introduction

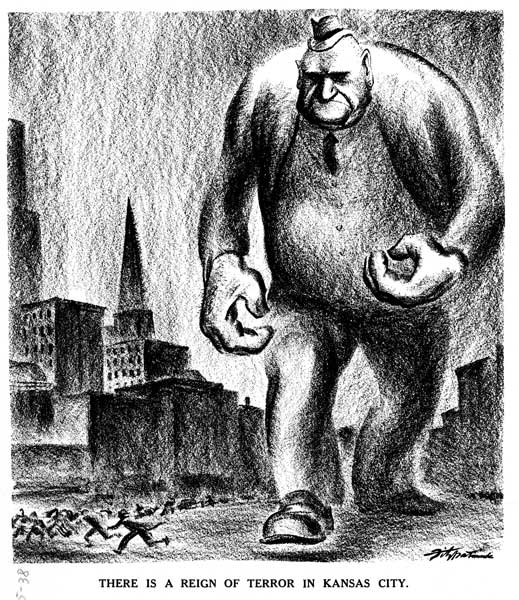

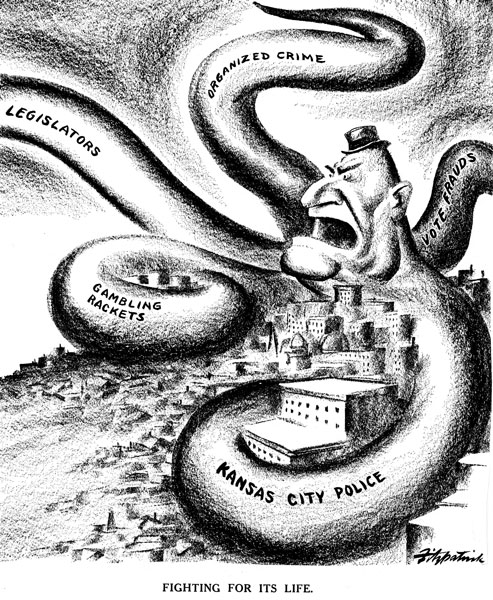

Thomas J. Pendergast was the leader of a Kansas City political organization known as the “Pendergast machine.” The Pendergast machine controlled local government and the Democratic Party in Kansas City and Jackson County, Missouri, during the Progressive Era and Great Depression. He finally lost power after a series of political scandals.

Early Years and Education

Thomas Joseph Pendergast was born on July 22, 1872, in St. Joseph, Missouri. He was the ninth and last child of Michael and Mary Reidy Pendergast, immigrants from County Tipperary, Ireland. Michael Pendergast worked as a teamster.

Tom attended school until at least the sixth grade. He later claimed to have attended college for two years, but no records have been found to support the claim. City directories and newspaper accounts, however, indicate that he worked a variety of jobs during his early years, including as a laborer, clerk, and grocery wagon driver.

Moving to Kansas City

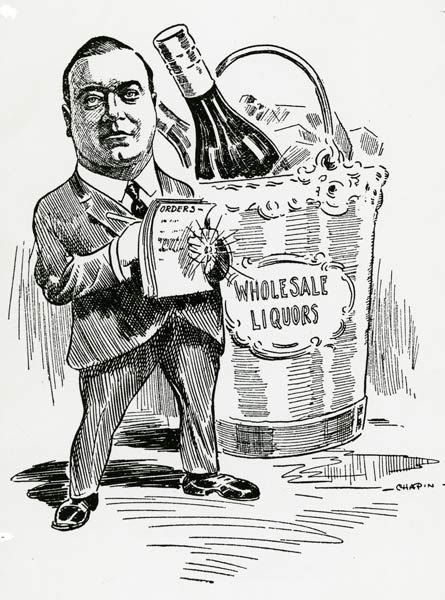

In 1894 Tom Pendergast permanently relocated to Kansas City, where he joined his brother James, a former packinghouse employee and ironworker who had risen to become a successful businessman and owner of the American House, a hotel and saloon. As James’s fortunes grew, he provided jobs for his many siblings. While his sisters Mary Anne and Josephine worked in the hotel, John and Michael Pendergast (who would also become involved in the machine) tended bar in the saloon. Tom Pendergast graduated from working odd jobs to serving as a bookkeeper for his older brother.

James had established himself in the West Bottoms, an industrial section of the city bordered by the Missouri River and the Kansas state line. The area was home to the city’s warehouses, rail yards, and packinghouses, as well as to the black, immigrant, and poor white workers who toiled in them. It had poor roads and sanitation and the housing was overcrowded and in disrepair. Saloons like the ones owned by James were important places in neighborhoods like the West Bottoms. They provided recreation for workers (especially men) who worked long hours, and they served as banks in a part of the city where few others provided the service. James later extended his influence into the North End, another neighborhood of working-class people which bordered the West Bottoms.

Entry into Politics

Well-known by their neighbors, saloonkeepers often made the leap from businessman to politician, and James Pendergast was no different. Their popularity made them successful in the ward system of politics. At the turn of the century, cities were often divided into units called wards. Politicians were elected from these wards to represent their neighborhoods in city government.

In 1892 James was elected alderman of Kansas City’s First Ward. He used his position as an elected official to advance the interests of his largely working-class constituents. He promoted using city funds to establish a garbage system, and he supported the construction of a park accessible to the area’s residents. He also opposed a deal between the city and a telephone company that he feared would make telephone service too expensive, a scheme to remove the only fire station in the West Bottoms, and cutting the pay of firemen.

Of course, James’s actions were not always good for the neighborhood and its residents. Like many other urban areas, Kansas City’s working-class neighborhoods were also locations for various forms of vice, including gambling, drugs, and prostitution. As a saloon owner and politician in a working-class ward, James benefited financially from the vice industries (especially gambling), and he used his political power to protect them.

Tom Pendergast studied how to succeed in ward politics from watching and assisting his brother’s efforts. During the nineteenth century, many government jobs were awarded based on political connections. Reformers criticized this system for giving jobs to unqualified people, but the system also allowed working-class and immigrant residents to get jobs that were previously reserved for members of the white, native-born (and usually Protestant) elite. In 1894 James gave his younger brother a job as a deputy constable in the First Ward city court. Two years later, Tom was appointed deputy marshal in the county court. In 1900 Kansas City mayor James A. Reed (an ally of James’s) appointed Tom to a two-year term as superintendent of streets.

James was increasingly slowed by illness after 1900, and Tom stepped in to help him with his duties as alderman. It was during this period that Tom Pendergast began his rapid ascent as a political leader in Kansas City politics. When James died in 1911, Tom ran for his brother’s seat on the city council and won.

"Tom's Town"

As a city alderman, Tom Pendergast sought to strengthen his control over Democratic politics in Kansas City. James had been prevented from being the undisputed boss of Kansas City by Joseph Shannon, the leader of the Democrats in the city’s Ninth Ward. Pendergast’s followers were known as the “Goats” and Shannon’s were the “Rabbits,” nicknames which, according to one historian, reflected animals popular with the Irish residents of the wards they represented. To prevent conflict between the two sides, they established a compromise by which they split control of political jobs (like deputy marshal) in Jackson County in a so-called “Fifty-Fifty” compromise.

Over time, this compromise broke down, and Pendergast and Shannon fought for control. By 1925 Pendergast had forced Shannon into a subordinate role. Only a decade after resigning from the city council in 1915, Pendergast had emerged as the most powerful figure in Democratic politics in the city and county.

As the machine grew in power, it continued to attend to the needs of poor and working-class Kansas Citians. Like his brother, Pendergast used his organization to finance the distribution of food, coal, and clothing to needy residents of the First Ward. Perhaps his best known charitable activities were the Christmas and Thanksgiving dinners for the poor. According to one historian, “At a typical holiday meal in 1930, more than three thousand homeless men of all races formed a line of several blocks.”

During the Great Depression, when large numbers of the city’s residents could not find work, Pendergast and his associates devised a plan to replace labor-saving machines with people power. Of course, these efforts to aid the poor and working class helped Pendergast, too. Workers repaid the boss with votes, and many of the projects were supplied by Pendergast-run businesses, especially the Ready-Mixed Concrete Company.

While gambling and profits from other vice industries enriched Pendergast, the city’s nightclubs also provided a home for artists, musicians, and other nonconformists. For example, jazz musicians who would become nationally known—most notably William “Count” Basie, Bennie Moten, and Charlie Parker—played in Kansas City clubs during the period when Pendergast oversaw the city’s nightlife.

Pendergast, however, could not have gained as much political power as he did with only working-class support alone. Kansas City had a large population of clerks and other white-collar employees. Since middle-class workers largely did not require the kind of social service help he provided to the poor and working class, Pendergast organized social events for those people who could not belong to the country clubs that served the needs of the city’s wealthiest residents. The machine organized baseball and bowling leagues as well as social clubs that held dinners, dances, picnics, and various kinds of parties during most of the year. Having built connections between people through sports and social events, the clubs then turned to politics during elections.

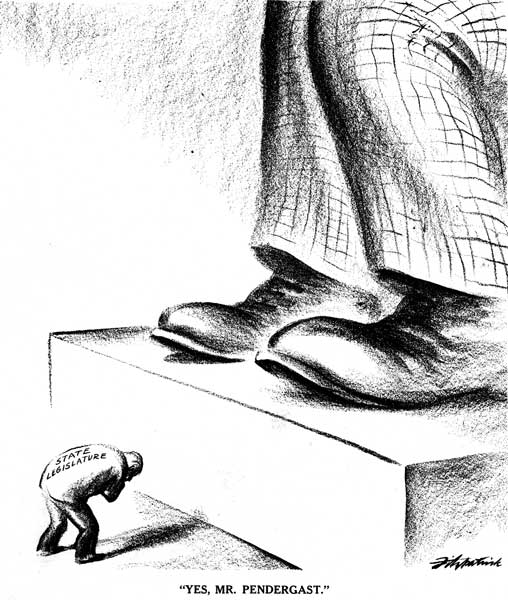

State and National Politics

Pendergast used his power base in the Kansas City area to extend his influence into Missouri state politics and even Washington, DC. In 1922 Pendergast supported Harry S. Truman for county judge in the Eastern District of Jackson County. Truman was one of many Kansas City and Jackson County politicians who Pendergast supported for office. Pendergast allegedly had so much influence over Missouri governor Guy Brasfield Park that the governor’s mansion became known as “Uncle Tom’s cabin.”

Perhaps Pendergast’s most important political victory came in 1934 with the election of Truman to the U.S. Senate. Truman was mocked as the “Senator from Pendergast” because of his ties to the notorious political boss. Truman, however, gained recognition for honesty and hard work in Washington, DC.

Investigations and Imprisonment

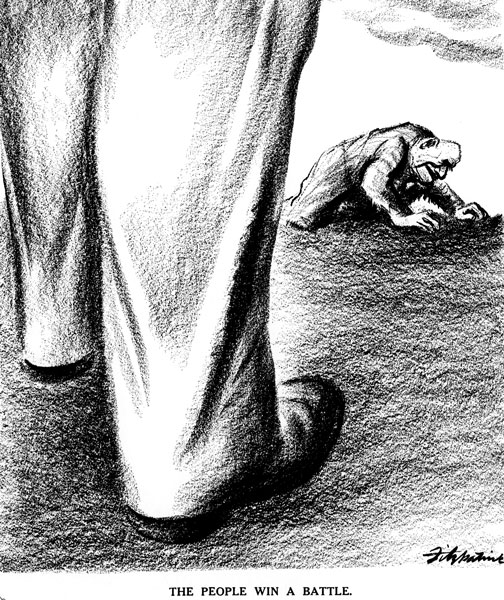

Pendergast’s machine was finally destroyed when one of the politicians he helped to create, Lloyd C. Stark, turned against him. With Pendergast’s approval, Stark was elected governor of Missouri in 1936. Stark, however, wanted more than the governor’s office; he wanted Harry Truman’s seat in the Senate. To get it, Stark decided to weaken Truman’s biggest supporter: Pendergast.

After a federal prosecutor found evidence that the machine had participated in voting fraud, Stark took his opportunity to turn on the boss. The vote fraud trials eventually indicted 278 people and over 200 went to jail for their role. Pendergast was not charged, but the illegal activities of the Pendergast machine angered many Democrats, especially in rural Missouri, where people received little if any direct benefit from it. Although Democratic president Franklin D. Roosevelt had initially supported Pendergast in return for votes, he dropped his support once it became clear that Missourians were turning against the boss and his machine.

Stark took advantage of this anger and Roosevelt’s flagging support to destroy the machine. At Stark’s request, federal authorities began an investigation into what would ultimately become known as the “Insurance Scam.” They found evidence that Pendergast had privately intervened in a lawsuit between the state of Missouri and private insurance companies in exchange for $750,000. Because he did not declare this money on his federal tax return, Pendergast was charged with federal tax evasion. Federal authorities proved that Pendergast failed to pay over half a million dollars in taxes for the years of 1935 and 1936 when the insurance scam was conducted. He pleaded guilty and was sentenced to one year and three months in prison plus five years probation. He was also ordered to pay a $10,000 fine.

Downfall of the Pendergast Machine

Pendergast’s political organization did not immediately collapse after he was sentenced to federal prison, but it was significantly weakened.

Efforts were made to clean up crime and corruption in Kansas City. Former FBI agent Lear B. Reed was appointed Chief of the Kansas City Police Department. Reed worked tirelessly to rid both the police department and the city of crime. City employees who owed their job to Pendergast were fired. Mayor John B. Gage pursued reform measures to end corruption in local government.

By the late 1940s the peak of the Pendergast machine was over. The machine’s decline, however, did not get rid of corruption in city government, nor did it solve longstanding social problems like poverty and street crime.

On January 26, 1945, the seventy-two-year-old Pendergast died from a heart attack in Kansas City, Missouri. He was buried in Forest Hill Calvary Cemetery in Kansas City.

Pendergast's Legacy

Tom Pendergast rose from poverty to become one of the most powerful political figures in Missouri even though he never held a major political office.

Pendergast’s control of the state Democratic Party was the result of fraud, manipulation, and violence at the ballot box as well as service to the people of Kansas City and Jackson County. He shaped the political landscape of Kansas City and the state of Missouri by controlling political candidates and influencing the outcome of elections. His downfall signaled the end of machine politics in Missouri.

Text and research by Kimberly Harper, Stephanie Kukuljan, and John W. McKerley

References and Resources

For more information about Thomas J. Pendergast’s life and career, see the following resources:

Society Resources

The following is a selected list of books, articles, and manuscripts about Thomas J. Pendergast in the research centers of The State Historical Society of Missouri. The Society’s call numbers follow the citations in brackets.

Articles from the Missouri Historical Review

- Alexander, Henry M. “The City Manager Plan in Kansas City.” v. 34, no. 2 (January 1940), pp. 145-156.

- Grothaus, Larry. “Kansas City Blacks, Harry Truman, and the Pendergast Machine.” v. 69, no. 1 (October 1974), pp. 65-82.

- Larsen, Lawrence H. “A Political Boss at Bay: Thomas J. Pendergast in Federal Prison.” v. 86, no. 4 (July 1992), pp. 396-417.

- Larsen, Lawrence H., and Nancy J. Hulston. “Criminal Aspects of the Pendergast Machine.” v. 91, no. 2 (January 1997), pp. 168-180.

- McLear, Patrick. “‘Gentlemen, Reach for All’: Topping the Pendergast Machine, 1936-1940.” v. 95, no. 1 (October 2000), pp. 46-67.

- McLear, Patrick. “Pendergast vs. State: Politics, Patronage, and the 1938 Supreme Court Democratic Primary.” v. 96, no. 3 (April 2002), pp. 188-210.

Articles from the Newspaper Collection

- “Boss Tom Got a $500,000 Bribe and Phoned a $10,000 Bet.” Kansas City Star. November 23, 1947. p. 1E. [Reel # 20720]

- “Death of Francis M. Wilson Failed to Upset Pendergast’s Sweep of the 1932 Election.” Columbia Daily Tribune. March 24, 1938. [Reel # 8207]

- “Figures Show Measure of Pendergast Success as Boss.” Columbia Daily Tribune. March 25, 1938. [Reel # 8207]

- “How Pendergast, Missouri’s First Boss Since ’96, Gets His Power.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. October 23, 1932. p. 1B. [Reel # 42422]

- “Tom Pendergast is Better at Picking Candidates Than Kentucky Derby Entries.” Columbia Daily Tribune. March 22, 1938. [Reel # 8207]

- “Tom Pendergast Gained Control of Democratic City Committee in Fall of ‘14” Columbia Daily Tribune. March 19, 1938. [Reel # 8207]

- “Tom Pendergast Resigned From City Council in 1915.” Columbia Daily Tribune. March 21, 1938. [Reel # 8207]

Books and Articles

- Christensen, Lawrence O., William E. Foley, Gary R. Kremer, and Kenneth H. Winn, eds. Dictionary of Missouri Biography. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1999. pp. 602-604 [REF F508 D561]

- Coghlan, Ralph. “Boss Pendergast: King of Kansas City, Emperor of Missouri.” Forum and Century. v. 97, no. 2 (February 1937), p. 67-72. [REF F508.1 P373c]

- Coulter, Charles E. “Take Up the Black Man’s Burden”: Kansas City’s African American Communities, 1865-1939. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2006. [REF H128.52 C832]

- Dillard, Irving. “Missouri’s Boss Pendergast.” The Nation. v. 143, no. 25 (December 1936). [REF F508.1 P373d]

- Dorsett, Lyle W. The Pendergast Machine. New York: Oxford University Press, 1968. [REF H128.74 D 738]

- Ferrell, Robert H. The Kansas City Investigation: Pendergast’s Downfall, 1938-1939. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1999. [REF F508.1 P373ha]

- Ferrell, Robert H. Truman and Pendergast. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1999. [REF F508.1 T771fe5]

- Irey, Elmer, and William J. Slocum. “How We Smashed the Pendergast Machine.” Coronet. v. 23, no. 2 (December 1947), p. 67-76. [REF H128.74 Ir2]

- Larsen, Lawrence H., Nancy J. Hulston. Pendergast! Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1997. [REF F508.1 P373l]

- Milligan, Maurice M. Missouri Waltz: The Inside Story of the Pendergast Machine by the Man Who Smashed It. New York: Scribner’s Sons, 1948. [REF H128.74 M621]

- Powell, Eugene J. Tom’s Boy Harry: The First Complete, Authentic Story of Harry Truman’s Connection with the Pendergast Machine. Jefferson City, MO: Hawthorn, 1948. [REF F508.1 T771p]

- Reddig, William M. Tom’s Town: Kansas City and the Pendergast Legend. New York: Lippincott, 1947. [REF H128.74 R245]

- Schirmer, Sherry Lamb. A City Divided: The Racial Landscape of Kansas City, 1900-1960. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2002. [REF H128.52 Sch 35]

Manuscript Collection

- Park, Guy Brasfield (1872-1946), Papers, 1932-1937 (C0008)

Official and personal correspondence and papers of Guy B. Park, Democratic governor of Missouri from 1933 to 1937. References to Pendergast are located throughout the collection. - Pendergast, Thomas J., Jr. (1913-1990) Papers (K0316)

The collection consists of the papers of Thomas J. Pendergast, Jr., the son of “Boss” Tom Pendergast. - Stark, Lloyd Crow (1886-1972), Papers, 1931-1941 (C0004)

The papers of the Democratic governor of Missouri, 1937-1941, relates to official business, campaigns, and personal affairs. References to Pendergast are located throughout the collection. - Reform Movement Oral History Project (K0266)

This collection consists of interviews with people active in the Kansas City reform movement from the 1920s through the 1950s. The reform movement was a reaction to the Pendergast machine’s control of the city.

Outside Resources

These links, which open in another window, will take you outside the Society’s website. The Society is not responsible for the content of the following websites:

- Colburn, David R. and George E. Pozzetta. “Bosses and Machines: Changing Interpretations in American History.” The History Teacher. v. 9, no. 3 (May 1976), pp. 445-463.

- Stave, Bruce M., John M. Allswang, Terrence J. McDonald, and John C. Teaford. “A Reassessment of the Urban Political Boss: An Exchange of Views.” The History Teacher. v. 21, no. 3 (May 1988), pp. 292-312.