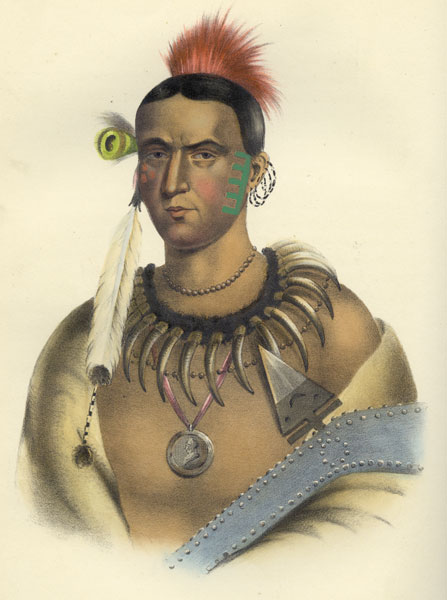

White Cloud

Introduction

White Cloud was a leader of the Ioway, or Baxoje (pronounced bock-HO-jay), people during a very difficult time in their history. When he was a young man, European American settlers were rare in Missouri and the Ioway were able to live as they had for centuries. But as he grew older and the population of white settlers became larger, his people struggled to live in the quickly changing world. White Cloud worked hard to make sure that his people survived in this new environment. Some of the decisions he made were not popular with the United States government and others made some of his own people angry.

Early Years

White Cloud was born sometime around 1784, probably in a village along the Des Moines River where the present states of Iowa and Missouri meet. Like all Ioway children of his time, White Cloud had many names. When he was born, his parents gave him a birth name. When he was still a child, the elders of his clan, the Bear Clan, gave him a clan name. As he became a man and proved his bravery in battle, he may have chosen a name to remind others of his courage, or to mark an important event in his life. All of these names have been forgotten and we only know that he was called White Cloud. European Americans also commonly called him Mahaska. This name comes from MaxúThka (pronounced mock-WHO-thka), which means “White Cloud” in the language of the Ioway people.

When White Cloud was still too young to have had a chance to prove himself as a warrior, some Dakota Sioux men killed his father, MaHága (pronounced ma-HA-ga), or “Wounding Arrow,” in an ambush. Because Wounding Arrow was an Ioway leader, White Cloud was expected to take his father’s place.

Over the next few years, White Cloud worked to prove his bravery in battle. By that time the Ioways were living in what is now northern Missouri. With the help of the Sacs and Foxes, the Ioways were able to hunt as far south as the Missouri River. The river marked the beginning of the territory that belonged to their enemies, the Osage tribe. As a young man, White Cloud claimed to have fought in eighteen battles. Many of those were against the Osage.

Convicted of Murder

In 1808, when White Cloud was in his mid-twenties, he was arrested for murder. White Cloud and one other Ioway man, known by the French name Mira Natutais, were trying to cross the Missouri River near the site of present day Brunswick, Missouri. While they were on the riverbank, they exchanged gunfire with some traders who were on the river in boats. As a result two traders, Joseph Tibeau and Joseph Marechal died. The two Ioways were taken to St. Louis where they were convicted of murder and sentenced to death. However, Judge John B.C. Lucas granted the two a new trial because the crime had taken place on land that was still owned by the Native Americans. Lucas believed that the territorial court had no authority over crimes committed there. While they were in jail waiting for their new trial, both White Cloud and Mira Natutais escaped.

An American Ally

After returning to his people, White Cloud vowed never to fight the Americans again. When he was young, there had not been many settlers on the Ioways’ land, but by 1810, he believed there were too many to fight. It was then that White Cloud realized that if his people were to survive, they had to cooperate with the Americans.

Not all of the Ioways agreed with White Cloud. When the War of 1812 began, some Ioways joined some Sacs and Foxes to fight on the side of the British, who were trying to chase the Americans out of Missouri. White Cloud joined the side of the Americans but instead of fighting, he and the Ioways who supported him, moved to western Missouri to be away from the violence.

Treaties with the United States

Even after Missouri entered the Union as the twenty-fourth state in 1821, many indigenous nations had rights to large parts of the state’s land. The Ioways and the Sacs and Foxes claimed rights to all of the state that was north of the Missouri River. In 1824 the United States government decided to buy those rights from the Native Americans.

White Cloud, along with his wife Rut^ánweMi (pronounced root-AN-way-me), or Female Flying Pigeon, and another Ioway leader named MáñiXáñe (pronounced MON-yee-HON-yay), or Great Walker, traveled to Washington DC to meet with President James Monroe and Superintendant of Indian Affairs Thomas McKenney. Once in the capital city, the Ioways were treated to fancy parties and to tours of factories and shipyards. All three Ioways also had their portraits painted by the famous American artist, Charles Bird King.

When White Cloud and Great Walker finally met with McKenney, they agreed to sell their rights to all Ioway land between the Missouri River and Missouri’s northern border for $5,000. The United States government wanted to teach the Ioways to farm in the same way that their white neighbors did. The government also agreed to provide the tribe with a blacksmith, farm machinery, tools, and cattle. As part of the treaty, the Ioways promised to leave the state of Missouri by January 1, 1826.

As soon as they returned to Missouri, however, Great Walker regretted signing the treaty. He vowed never to leave the state and settled along the Chariton River in north central Missouri with several of his followers. White Cloud kept his promise and moved with his followers to the site of a new Ioway Agency, located near the present-day town of Agency, near St. Joseph, Missouri. At that time, Missouri’s western border was different than it is today. Instead of following the Missouri River north of Kansas City, the old state border ran directly north from the city. The land west of the old boundary line and east of the Missouri River was called the Platte country after the Platte River that ran through it. That land was intended to be a place where Native Americans could live without fear of having their land taken by settlers.

In 1830 White Cloud was one of nine Ioway leaders who attended another treaty council at Prairie du Chein, in present day Wisconsin. In the council, he told the U. S. representatives that he had followed their advice and learned to live and farm like a white man and that he had given up war forever. A few days later, the Ioways signed a treaty that sold all of the Platte country and western Iowa to the United States. Later, the Ioways complained that, because of their poor understanding of English, they did not understand the treaty they had signed and that they had not intended to sell their land. They were able to postpone the sale of the land, but only for six years.

A Violent End

By the early 1830s Missouri was growing in population and settlers were eager for more land. Soon, European Americans were settling illegally in the Platte country. Some moved so close to the Ioway Agency that their cattle destroyed the Ioways’ cornfields. The Ioways were too few in number to defend the land by themselves and White Cloud asked for help from the U. S. government. But even armed soldiers could not keep these illegal settlers, called squatters, off of the tribe’s land.

The Ioways also had problems protecting themselves from the violent acts of neighboring indigenous tribes. There was not enough wildlife to feed the growing number of settlers and Native Americans living in the Platte country. Sometimes Native Americans were so desperate for food that they raided the nearby villages of other tribes.

In June 1831 a group of Omahas traveled along the Missouri River to their village with a shipment of food, clothing, and money the government had paid them as part of a treaty settlement. The Omahas were worried that they would be attacked by a band of Sac and Fox warriors, who were rumored to be in the area. As they traveled, the Omahas met a small group of Ioways and, believing they were bandits, attacked them. The son of an Ioway leader named Péchan (pronounced PE-chan), or “Crane,” died in the battle. After the attack, some Ioway warriors asked White Cloud for permission to avenge the man’s death by raising a war party to raid the Omaha. White Cloud said no, demanding instead that the United States government settle the matter by punishing in the courts the Omaha men who were responsible for the murder of Crane’s son.

The government was slow to act and two years later twelve frustrated Ioway men took matters into their own hands. They killed six Omahas in a raid and took a woman and a boy hostage. White Cloud helped the U.S. government arrest eight of the Ioways who were responsible for the raid. While in prison in Fort Leavenworth, one of the Ioway men vowed to kill White Cloud for helping to arrest him. A year later, the man escaped and, with the help of a small number of others, followed White Cloud to a hunting camp in southwest Iowa and killed him. White Cloud was about fifty years old when he died in 1834.

Legacy

As a leader of the Ioway, it was White Cloud’s job to make sure that his people had everything they needed to survive. But as settlers flooded onto the Ioways’ land in Iowa and Missouri, that job became very difficult. While some wanted him to resist the white settlers, White Cloud believed that the Ioways could only survive by working with them. After the United States government took over Missouri, White Cloud accepted the U.S. officials as leaders and did his best to follow their laws and advice. While the process was long and difficult, the Ioway have survived. Today they are successful farmers and business people who still maintain a reservation in northeast Kansas and another in north central Oklahoma.

Text and research by Greg Olson

References and Resources

For more information about White Cloud’s life and career, see the following resources:

Society Resources

The following is a selected list of books, articles, and manuscripts about White Cloud in the research centers of The State Historical Society of Missouri. The Society’s call numbers follow the citations in brackets.

Articles from the Missouri Historical Review

- Olson, Greg. “Navigating the White Road: White Cloud’s Struggle to Lead the Ioway Along the Path of Acculturation.” v. 99, no. 2 (January 2005), pp. 93-114.

Books and Articles

- Blaine, Martha Royce. The Ioway Indians. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1995. [REF 970.3 B574]

- Foley. William E. “Different Notions of Justice: The Case of the 1808 St. Louis Murder Trials.” Gateway Heritage. v. 9, no. 3 (Winter 1988-1989), pp. 2-13. [REF F550 M69gh v. 9]

- McKenney, Thomas L. and James Hall. “Mahaskah.” History of the Indian Tribes of North America. Philadelphia: D. Rice and A. N. Hart, 1855. v. 2, p. 217. [REF Bay Coll. v. 2]

- Meriwether, David. My Life in the Mountains and on the Plains. Ed. Robert A Griffen. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1965. [REF 921 M5451]

- Olson, Greg. The Ioway in Missouri. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2008. [REF 921 M5451]

- Olson, Greg. “Two Portraits, Two Legacies: Anglo-American Artists View Chief White Cloud.” Gateway. v. 25, no. 1 (Summer 2004), pp. 20-31. [REF F550 M69gh v. 25]

Manuscript Collection

- John Dougherty Letter Book, 1826-1829 (C2292)

The Dougherty letter book contains letters from Dougherty, fur trader, interpreter, and Upper Missouri Indian agent, to William Clark, superintendent of Indian affairs at St. Louis, various U.S. Army officers, Indian agents, interpreters and fur traders, U.S. War and Treasury Department officials, Missouri politicians, and private citizens. The collection includes references to White Cloud.

Outside Resources

- Ioway, Otoe-Missouria Language Website

This website provides information about the language of the Ioway. - Ioway Cultural Institute

Information about the Ioway or Iowa Tribe can be found at this website. - Olsen, Greg. “Mahaska (White Cloud).” The Biographical Dictionary of Iowa. David Hudson, et al, eds. Iowa City: The University of Iowa Press, 2008. pp. 334-335.