Daniel Boone

Introduction

Daniel Boone is one of the most famous frontiersmen in U.S. history. He was a skilled hunter, trapper, and trailblazer. During the early days of westward expansion, Boone’s explorations helped open the frontier to new settlements. In 1799, he led his family and other settlers across the Mississippi River into land populated by Native Americans but claimed by Spain. Boone spent the last twenty years of his life in what is now Missouri.

Early Years

Daniel Boone was born November 2, 1734, in Berks County, Pennsylvania. Sometimes, an alternate birth date is listed because the Boone family used an outdated calendar system and recorded Daniel’s birth on October 22. Daniel was the sixth of eleven children born to Squire and Sarah Boone, both Quakers. Boone’s father had grown up in England but had immigrated to the New World as a teenager.

As a child, Daniel was responsible for taking the family’s cattle into the woods to graze each day. Daniel loved wandering the woods with the cows. The outdoors fascinated him, and he spent his days studying small birds and game, which he hunted with a homemade “herdsman’s club.” Daniel begged for a rifle and became an expert marksman. At thirteen, he provided a steady supply of fresh game for the family’s meals.

Daniel Boone did not attend school. His older brother’s wife taught him to read and write. Though he mastered the basics, Boone’s grammar and spelling remained poor. Boone could sign his name, though, which set him apart from most frontiersmen, who used an “X” for their signature.

Around 1750 the Boones moved to North Carolina and settled in the Yadkin River valley. The Native Americans who lived and hunted there did not like sharing their land with the settlers. Fights frequently broke out between the two groups, and Boone joined the county militia to help defend the settlements.

Fights Alongside British

In 1755, Daniel Boone went to fight in the French and Indian War. The war erupted in 1754 when France and Britain began fighting over territory in North America. It was called the French and Indian War because the Native Americans fought mostly alongside the French. At the time, the colonies had yet to gain independence from England, so the settlers fought alongside the British.

Boone joined British Major General Edward Braddock on his march to attack Fort Duquesne, a French fortification located in present-day Pittsburgh. George Washington—then a young colonial militia leader—also joined the march. During the trip, Boone worked as a wagoner alongside a trader named John Findley who had trekked to the Native American villages in Ohio and beyond. John told Boone about a place the Native Americans called “Kentucke”—a hunting ground packed with deer, buffalo, bear, and turkey. As the men neared Fort Duquesne, they were overpowered and suffered huge losses. Boone grabbed a horse from his wagon team and escaped, eventually returning to North Carolina but dreaming of Kentucky.

Hunts and Explores Frontier

Boone married Rebecca Bryan on August 14, 1756. Together they had ten children, six sons and four daughters. For the next several years, he made his living as a hunter and trapper. Boone disappeared for days, and sometimes months, into the Appalachian Mountains. Deer hides-used for clothing-were always in demand.

Eventually, Boone’s teamster friend, John, sought him out and asked Boone to accompany him on a trip to Kentucky. Joined by four others, they set out in 1769 and crossed through the Appalachians via the Cumberland Gap. Few white men had dared to cross the mountains. The men built a base camp near what is now Irvine, Kentucky, and spent several months hunting and exploring the great wilderness.

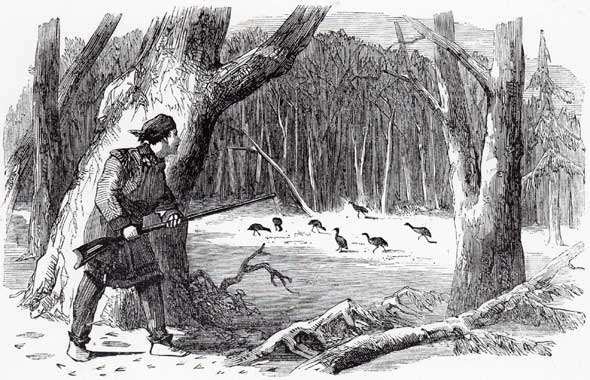

Boone traveled the frontier wearing buckskin leggings and a loose-fitting shirt made of animal skin. On his leather belt he attached a hunting knife a hatchet, a powder horn, and a bullet pouch. Many images portray Boone wearing a coonskin cap, which was popular with trappers. Boone preferred wide-brimmed beaver felt hats to keep the sun out of his eyes.

The Shawnee captured Boone’s hunting party several months into the expedition. They claimed the area as their hunting ground and believed anything caught there belonged to them. The Shawnee took the men’s supplies and deerskins. Boone escaped and finally returned home in March 1771, penniless and empty-handed.

Boone's Family

Moves West into Kentucky

In 1775 a friend hired Boone to cut a path into Kentucky for a new settlement on land purchased from the Cherokee. Boone led about thirty axmen through the wilderness to clear a path, which eventually became a route to the new frontier and was called the Wilderness Road. When the group reached the Kentucky River, they built a fort and called it Boonesborough. Other settlers followed, and Boone brought his family, too.

Life on the frontier was dangerous. Native Americans frequently attacked Boonesborough, hoping to drive the settlers back east. In 1776, Boone’s daughter Jemima was kidnapped by a small group of Shawnee and Cherokee men while canoeing on the river. Boone led a rescue party that retrieved Jemima and her friends two days later.

Boone was captured by the Shawnee in 1778. Impressed with Boone’s scouting and hunting skills, the Shawnee chief adopted Boone as one of his own. Boone lived among the Shawnee for four months before escaping and returning to Boonesborough. By 1798, Boone had lost all of his land in Kentucky due to title errors and debt.

Finds a Home in Missouri

In 1799, Boone decided to move farther west, into the land that is now Missouri but at the time was called Upper Louisiana. He built a canoe from a six-foot poplar tree so he could move some household items by river. Boone made the journey with his wife, two of his daughters and their husbands, and son Daniel Morgan Boone. Several other Kentucky families came along, and son Nathan Boone soon followed.

Spanish authorities, eager to have settlers in the area, granted Boone 850 acres in the Femme Osage District, now part of St. Charles County. He was made a commandant, or syndic, of the Femme Osage District. As a syndic, Boone settled disputes that arose among the area settlers. He became famous for holding court under a large tree on his son Nathan’s land. This tree was known as the “Judgment Tree.”

In 1804, Boone lost his land claims after Spain had transferred the territory to France, which in turn sold it to the United States. Boone remained in the area, living on land family members had secured. Rebecca Boone died in 1813, and Boone spent his remaining years living with his children. In 1820 painter Chester Harding visited Boone and painted the only known portrait made during his lifetime.

Daniel Boone died at Nathan Boone’s home in Defiance, Missouri, on September 26, 1820. He was buried next to his wife in a Marthasville-area cemetery.

Home of Nathan Boone in Defiance, Missouri.

In 1815, Nathan Boone was discharged from the Missouri Rangers and moved back into his log home at Femme Osage. Around this time, he started building a new house on his property—a large stone home that signified his rising status in the community.

Nathan constructed the walls from native limestone. The walls are two and a half feet thick. He used oxen to drag chunks of blue limestone to his property. Daniel Boone helped oversee construction of the home and is said to have carved the walnut mantelpieces for the seven fireplaces. The house also includes black walnut beams and oak floorboards. There is a ballroom on the top level.

The home sits on a hill overlooking the river. Although the home appears to be a two-story from the front, the back is four stories tall and has two stories of full-length porches from which to enjoy the view. The home also sports several rifle slots—or gun ports. On the frontier, the gun ports were necessary in the event of an attack.

The house is often referred to as the “Daniel Boone Home,” but it was actually Nathan’s home. Daniel Boone lived in the home from time to time and did spend his final moments there, dying in a first-floor bedroom in 1820.

The house, which sits near Defiance, has been preserved and is open for tours year-round.

Boone's Legacy

Soon after his death, the Missouri legislature honored Daniel Boone by naming Boone County after him. Many other states have also honored the legacy of Daniel Boone. Though it has been more than 180 years since he died, Daniel Boone and stories of his adventures continue to attract interest. Generations later, people still identify with his restless, wandering spirit, which compelled him to push the boundaries of existence.

Text and research by Lisa Frick

References and Resources

For more information about Daniel Boone’s life and career, see the following resources:

Society Resources

The following is a selected list of books, articles, and manuscripts about Daniel Boone in the research centers of The State Historical Society of Missouri. The Society’s call numbers follow the citations in brackets.

Articles from the Missouri Historical Review

- Amyx, Clifford. “The Authentic Image of Daniel Boone.” v. 82, no. 2 (January 1988), pp. 153-164.

- Asbury, Virginia Hays, and Albert N. Doerschuk. “The Boone, Hays and Berry Families of Jackson County.” v. 23, no. 4 (July 1929), pp. 536-549.

- Bryan, William S. “Daniel Boone in Missouri.” v. 3, no. 4 (July 1909), pp. 293-299.

- Bryan, William S. “Peculiarities of Life in Daniel Boone’s Missouri Settlement.” v. 4, no. 2 (January 1910), pp. 85-91.

- King, Roy T. “Portraits of Daniel Boone.” v. 33, no. 2 (January 1939), pp. 171-183.

- Shoemaker, Floyd C. “Daniel Boone.” v. 21, no. 2 (January 1927), pp. 208-214.

Articles from the Newspaper Collection

- “Daniel Boone.” Jefferson City Inquirer. August 7, 1845. p. 2, col. 5. [Reel # 16350]

- “Daniel M. Boone.” Jeffersonian Republican. August 3, 1839. p. 2, col. 4. [Reel # 16360]

- “Funeral Obsequies of Daniel Boone.” Jefferson City Inquirer. October 2, 1845. p. 2, col. 3. [Reel # 16350]

- “The Great Frontiersman Upon Whom Both Kentucky and Missouri Have Claims.” Kansas City Star. June 14, 1925. p. 1. [Reel # 20491]

- “Missouri, Kentucky Fight Over Daniel Boone’s Burial.” Chillicothe Constitution-Tribune. January 18, 1988. p. 7. [Reel # 6461]

- “New Names in the Hall of Fame Include the Great Pioneer.” Kansas City Star. October 11, 1915. p. 12. [Reel # 20360]

- “Obituary: Col. Daniel Boone.” Missouri Gazette & Public Advertiser. October 4, 1820. p. 3, col. 5. [Reel # 41287]

- “Portrait of Daniel Boone.” St. Louis Globe-Democrat Sunday Magazine. November 22, 1959. pp. 17-18. [Reel # 40385]

- “To the Editors of the Missouri Intelligencer.” Missouri Intelligencer. August 27, 1819. p. 2, col. 5. [Reel # 11512]

Books

- Abbott, John S. C. Daniel Boone: Pioneer of Kentucky. New York: Dodd & Mead, 1872. [REF F508.1 B644a]

- Bakeless, John. Daniel Boone: Master of the Wilderness. New York: William Morrow & Co., 1939. [REF F508.1 B644ba c.2]

- Bruce, H. Addington. Daniel Boone and the Wilderness Road. New York: Macmillan Co., 1910. [REF F508.1 B644bru]

- Christensen, Lawrence O., William E. Foley, Gary R. Kremer, and Kenneth H.Winn, eds. Dictionary of Missouri Biography. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1999. pp. 98-101. [REF F508 D561]

- Draper, Lyman C. The Life of Daniel Boone. Edited by Ted Franklin Belue. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1998. [REF F508.1 B644dr]

- Ellis, Edward S. The Life and Times of Col. Daniel Boone, The Hunter of Kentucky. New York: Beadle & Adams, c. 1860. [Bay Collection]

- Faragher, John Mack. Daniel Boone: The Life and Legend of an American Pioneer. New York: Henry Holt, 1992. [REF F508.1 B644fa]

- Goellner, Glen. The Saga of a Man and a House. St. Charles, MO: Daniel Boone Shrine Association, c. 1956. [REF F508.1 B644go]

- Hammon, Neal O., ed. My Father, Daniel Boone: The Draper Interviews with Nathan Boone. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1999. [REF F508.1 B644dr2 c.1]

- Hurt, R. Douglas. Nathan Boone and the American Frontier. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1998. [REF F508.1 B646h]

- Lofaro, Michael A. Daniel Boone: An American Life. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2003. [REF F508.1 B644lo2]

Manuscript Collection

- Boone, Daniel (1734-1820), Affidavit, n.d. (C1467)

This is an affidavit written by Boone indicating that his son, Daniel Morgan Boone, had claimed 600 arpents of land in St. Charles, MO, as granted by Spanish Lt. Gov. Zenon Trudeau in 1797. Boone writes that his son inhabited and cultivated the land before October 1, 1800. - Boone, Daniel (1734-1820), Deed, 1815, (C1732)

Deed to William Cashio for land in St. Charles County purchased from Daniel Boone, 6 May 1815. - Boone, Daniel (1734-1820), Ephemera, n.d. (C1475)

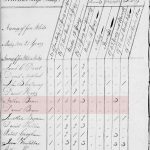

The collection contains a facsimile of pages from the Boone family Bible, noting birthdates for Boone, his wife, and children. Also included is a map sketch of Boone’s Pennsylvania birthplace. - Boone, Daniel (1734-1820), Papers, 1784-1787 (C2204)

Boone’s signature can be found here, as well as a court order written by Boone in 1787. There is also a Squire Boone account receipt from 1784. - Draper, Lyman Copeland (1815-1891), Collection, 1735-1815 (C2964)

Draper conducted extensive interviews with Nathan Boone and corresponded with other family members and frontier settlers. This is a microfilm copy of manuscripts from the Draper Collection. The originals are located at the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. - Draper, Lyman Copeland (1815-1891), Nathan Boone Interview, 1851 (C1212)

This collection includes Draper’s notes and comments from his interviews with Nathan Boone. It also contains recollections of Daniel Boone’s life and of other pioneers in Missouri and Kentucky.

Outside Resources

These links, which open in another window, will take you outside the Society’s website. The Society is not responsible for the content of the following websites:

- Archiving Early America

This site includes the text of the first three chapters of John Filson’s famed 1784 publication, The Adventures of Colonel Daniel Boon. The book made Boone a legend in his own time, although Filson stretched the truth in many instances, trying to make Boone’s adventures sound even more fascinating. - Boone Historical Sites

The Boone Society works to preserve documents and artifacts related to the Boone family. Their website contains lists of historic Boone sites around the country. - Daniel Boone Homestead

In addition to providing information and pictures of Boone’s birthplace in Pennsylvania, this website includes a brief biography on Boone and his family members. - Daniel Boone Wilderness Trail Association

This is the website for the Daniel Boone Wilderness Trail Association, an organization that provides information about the trail Boone forged through the wilderness into Kentucky. - Historic Daniel Boone Home at Lindenwood Park

This website offers information on the historic Boone Home in Defiance, Missouri. This is the stone home that Nathan built shortly after the family arrived in Missouri. It is also the home where Daniel Boone died.