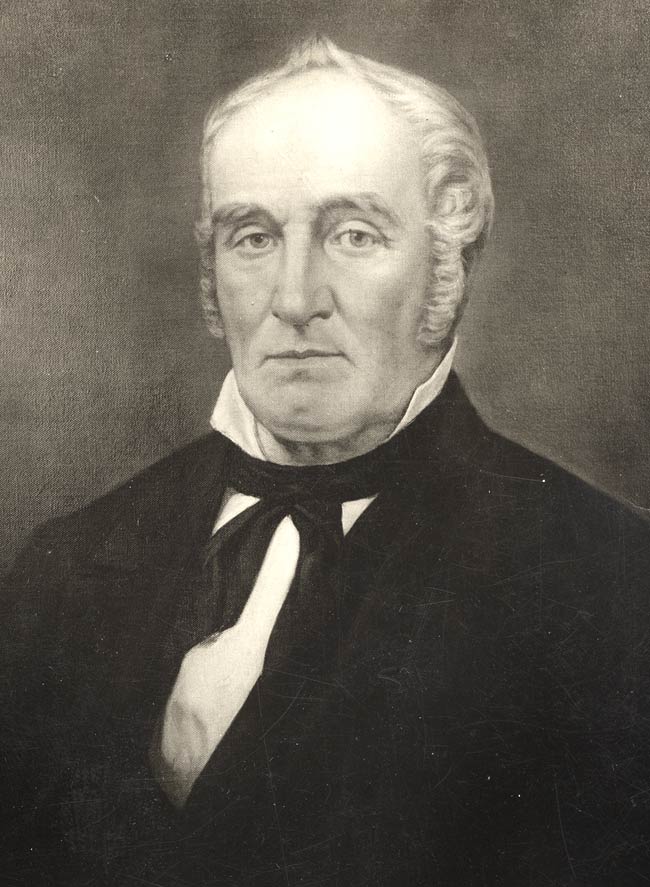

John S. Sappington

Introduction

Dr. John S. Sappington, a physician, farmer, and medical pioneer, developed an anti-malaria pill that helped save the lives of countless individuals who lived along rivers and in swampy areas. His discovery led one of his friends to declare that Sappington “deserve[d] a statue of gold to be erected by the mothers of Missouri.”

Early Years

John S. Sappington was born on May 15, 1776, in Havre de Grace, Maryland. He was the third of seven children born to Dr. Mark and Rebecca Boyce Sappington. John’s father studied medicine at the University of Pennsylvania and became a physician.

In 1785, when John was nine, the Sappington family moved to Nashville, Tennessee. He worked on the family farm and attended school. John later studied medicine with his father, who trained John and his brothers to become physicians. Because Tennessee was still part of the American frontier, doctors were in high demand, and John soon found himself busy tending to patients.

After completing medical studies with his father, John moved to Franklin, Tennessee, where he practiced medicine. In 1804, he married Jane Breathitt. Together they had nine children: two boys and seven girls. While he lived in Franklin, Sappington met future U.S. Senator Thomas Hart Benton. The two men became close friends. Benton, an influential lawyer and politician, urged Sappington to move to Missouri Territory where large tracts of land could be purchased at affordable prices from the U.S. government. Benton himself moved to Missouri in 1815.

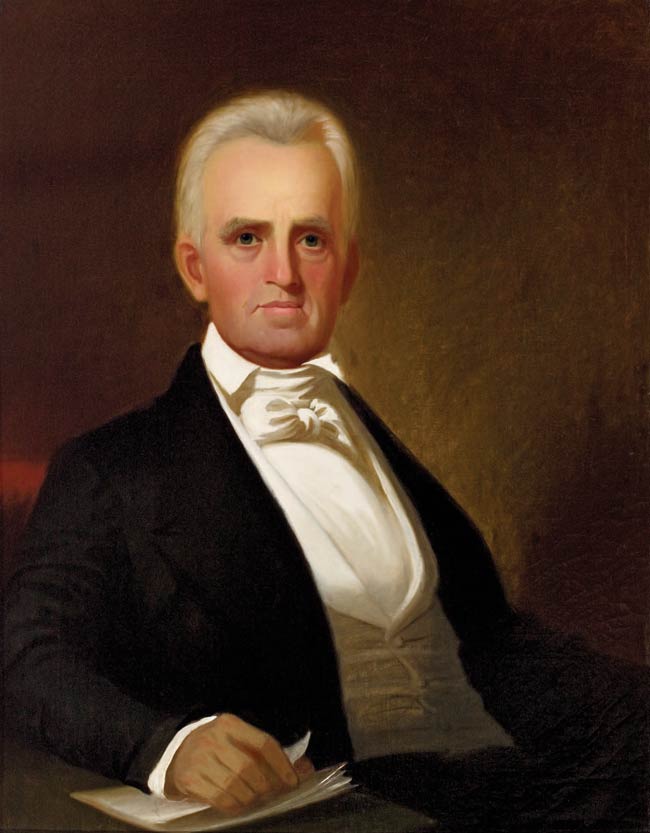

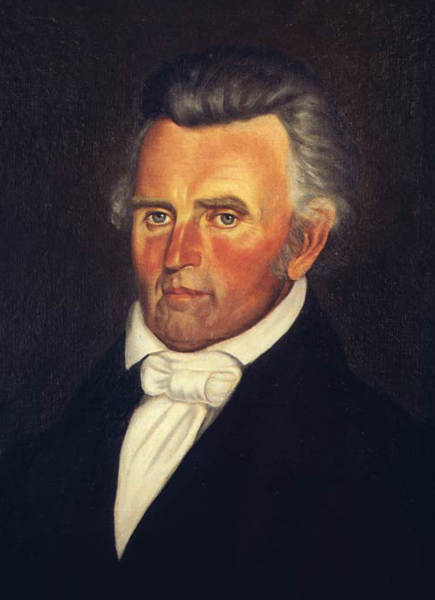

Sitting for George Caleb Bingham

In 1834 Dr. John Sappington and his wife Jane were painted by a promising local artist, George Caleb Bingham. The two portraits are the earliest known surviving portraits done by Bingham.

A New Beginning

Intrigued by Benton’s glowing description of the Missouri Territory and the opportunity to make money, Sappington traveled to the Boonslick region of Missouri. In 1804, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark had described the area as being full of salt water springs. Pleased by what he saw, Sappington borrowed $950 from Benton to purchase several thousand acres of land in what is now Saline County, Missouri. In 1819, Sappington and his family settled on a farm outside of Arrow Rock.

Sappington quickly became one of the most influential men in the region by providing medical services, lending money, and importing and exporting goods like cotton and medicine. His fortune also grew due to the hard work of people he enslaved to work his vast land holdings.

By 1824, Sappington established the Pearson and Sappington store at present day Napton and later opened a second store at Arrow Rock. The stores sold goods to travelers on the Santa Fe Trail, loaned money, processed salt, and milled lumber for locals. Dr. Sappington began to rely on relatives to help manage his businesses and land. It was the beginning of a family enterprise that lasted for decades.

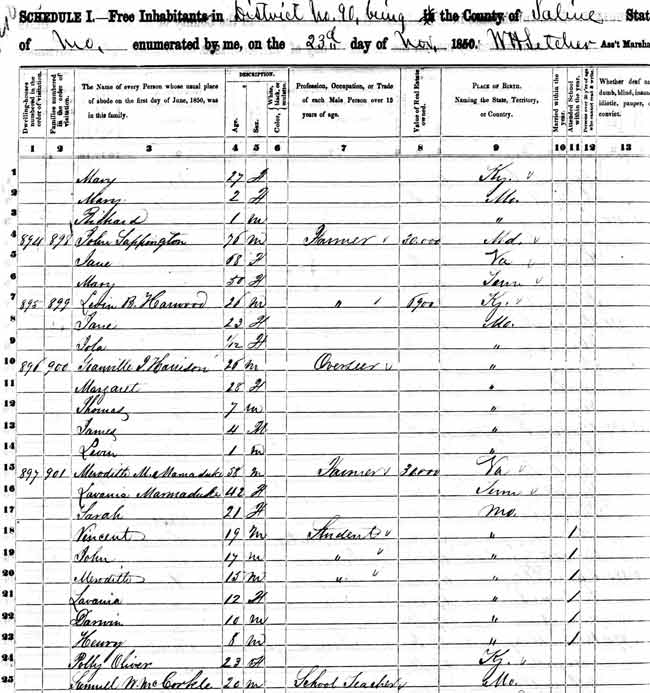

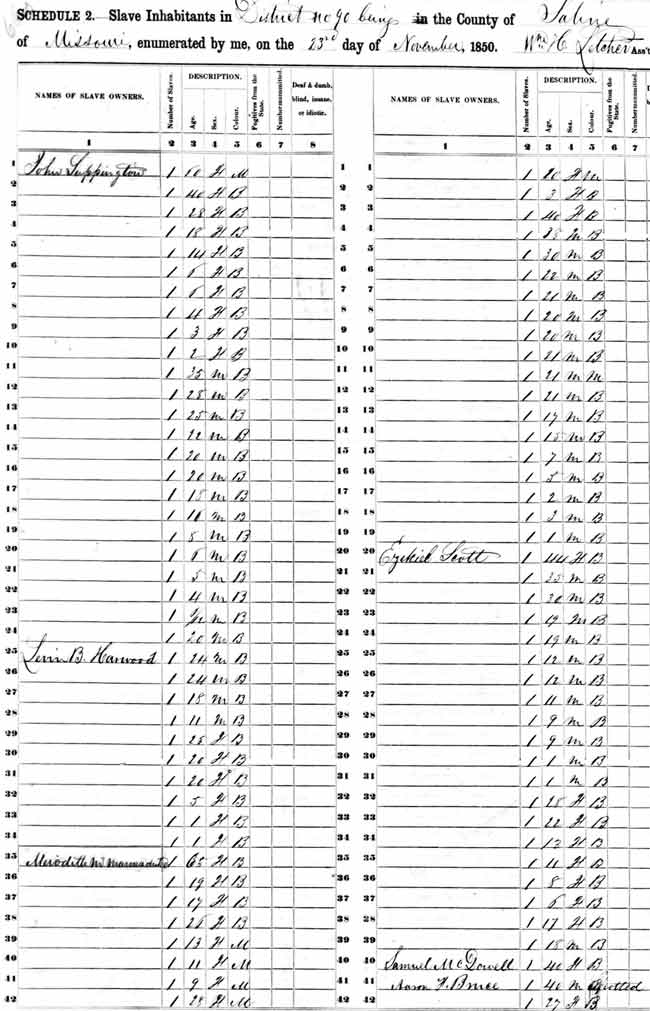

What the 1850 Census Tells Us about the Sappington Family

The 1850 U.S. Census lists John S. Sappington, his wife Jane, and one daughter, Mary. Also included is Sappington’s son-in-law and former Missouri Governor Meredith Miles Marmaduke, who married Sappington’s daughter Lavinia. Meredith and Lavinia’s 17-year-old son John Marmaduke, who would go on to becoome Missouri’s 25th governor (1885-1887), is listed as well.

On the slave schedule for the 1850 U.S. Census, Sappington is listed as enslaving 24 people. The average enslaver in Saline County owned 5.4 people.

Finding a Cure

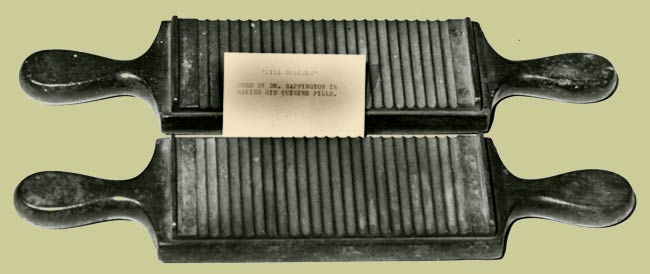

Financially successful, Sappington continued to practice medicine. He began to experiment with quinine, a substance derived from the bark of the cinchona tree, a species native to South America. Sappington began importing cinchona bark as early as 1820, but it was only years later that he discovered its most promising medicinal use as a preventative against malarial fever.

Malaria, an infectious disease passed from mosquitoes to humans, ravaged much of early America. People who lived near bodies of water or in areas of swampy, poorly drained land were among those most likely to contract the disease. Once infected, an individual suffered from high fever, chills, vomiting, and joint pain. Missourians who lived along the Missouri River and Mississippi River were often susceptible to malaria.

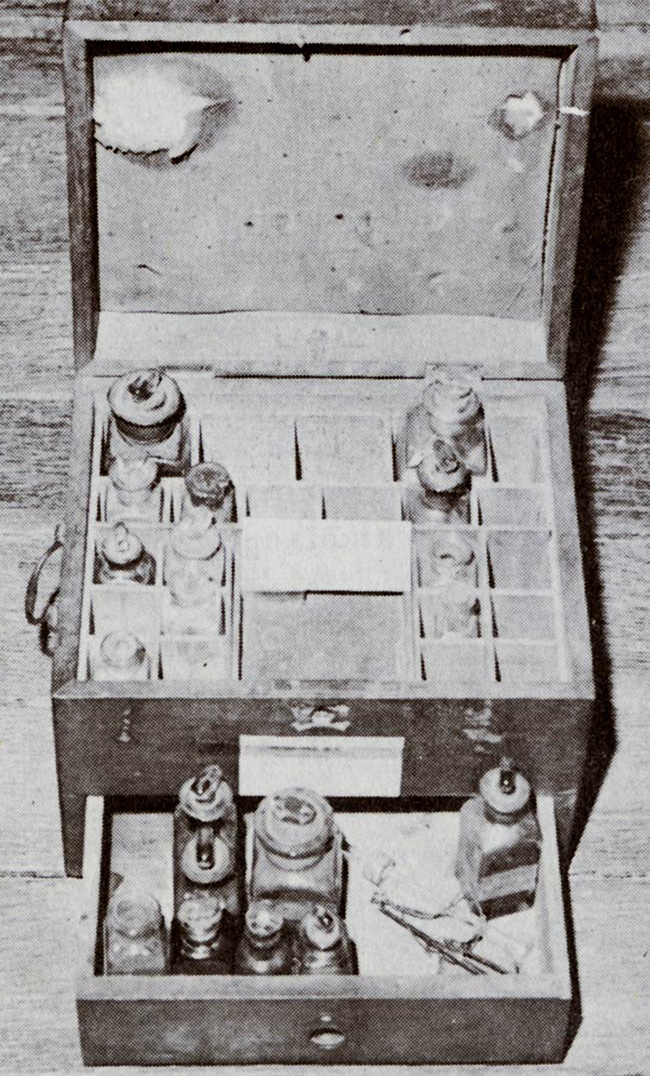

In 1832, using quinine taken from cinchona bark, Sappington developed a pill to cure a variety of fevers, such as scarlet fever, yellow fever, and influenza. He sold “Dr. Sappington’s Anti-Fever Pills” across Missouri. Demand became so great that within three years Dr. Sappington founded a new company known as Sappington and Sons to sell his anti-fever pills nationwide. The anti-fever pills were popular in Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas.

Sappington believed in sharing his success with less fortunate relatives and relied upon them to help him manage and sell his products all across the country. It was during this time that Sappington became aware of quinine’s protection against malaria. As his family members and other sales agents travelled through regions prone to sickness, Sappington instructed them to take the pills occasionally to ward off malaria. None of them became ill with the disease.

Controversy

His success did not come without controversy. At the time of Sappington’s discovery, many physicians did not believe in using quinine. Instead, the most common medical treatment at this time involved bleeding a patient and administering mercury chloride, also known as calomel. Although Dr. Sappington’s discovery worked, many doctors were still fearful of quinine and urged patients to avoid Sappington’s anti-fever pills because an incorrect dose could cause blindness or even death.

Despite criticisms of his pills, Dr. Sappington received letters from satisfied customers from all over the country. In one such letter, Rockwell Andrews of Havana, Illinois, wrote, “Your invaluable fever medicine having been tried in this town and vicinity and found to be what it was commended to be, a cure, there is a demand for it unequalled by any other medicine. In fact, no substitute can be found.”

In 1844, Dr. Sappington published the first medical book written west of the Mississippi River, Theory and Treatment of Fevers. Much to his family’s dismay, Sappington revealed the formula of his anti-fever medicine in his book, allowing physicians to manufacture their own anti-fever pills. Following the publication of his book, Sappington decided to divide his assets among his children and focus on agricultural pursuits.

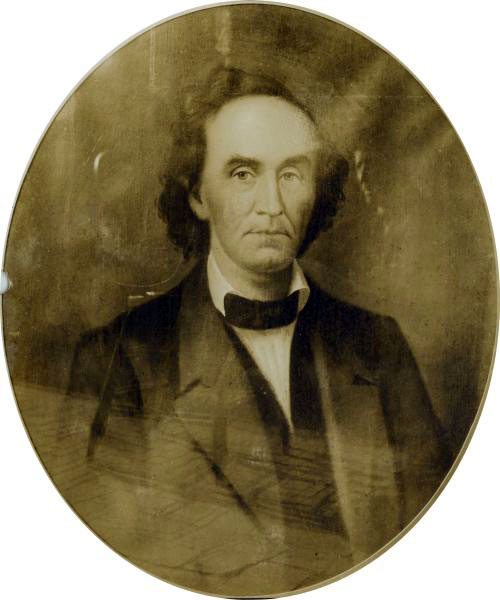

Dr. Sappington’s wealth and influence helped launch the political careers of several family members. Two sons-in-law, Meredith Miles Marmaduke and Claiborne Fox Jackson, became Governor of Missouri, as did Sappington’s grandson, John Sappington Marmaduke.

Philanthropy

Often described as an “avid reader,” Sappington believed in the value of education throughout his life. In 1847, he proposed the creation of a state manual training school to help educate and train Missourians, and even offered to give the state of Missouri land in exchange for its support. The state, however, failed to meet his offer and the school was never built.

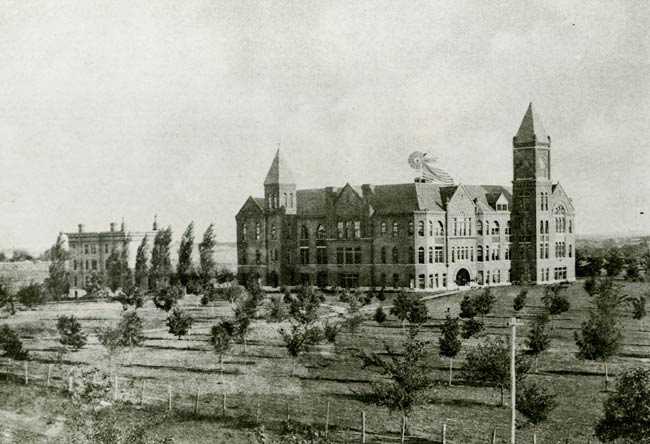

A few years later in 1853, Sappington established the Sappington School Fund, which he funded through a personal donation of $20,000. Because Missouri was still the western frontier and public schools were nonexistent, the Sappington School Fund helped underprivileged children pay to attend subscription schools. It also helped attract Missouri Valley College to Marshall, Missouri. The Sappington School Fund is still in existence today and is administered by Wood & Huston Bank in Marshall. In recent years, the fund has helped students obtain college educations.

Sappington's Legacy

After a long illness, Dr. John Sappington died on September 7, 1856, in Saline County. He is buried in Sappington Cemetery outside of Arrow Rock. The cemetery is a state historic site because his two sons-in-law who served as Governor of Missouri are buried there.

Although Dr. John Sappington’s successful creation of an anti-malaria pill did not eradicate malaria, it did help save thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of lives. Settlers were able to live in areas plagued by malaria in the American South and West. Through his financial generosity, Dr. Sappington helped hundreds of Missourians receive an education and better their lives.

Text and research by Kimberly Harper

References and Resources

For more information about John S. Sappington’s life and career, see the following resources:

Society Resources

The following is a selected list of books, articles, and manuscripts about John S. Sappington in the research centers of The State Historical Society of Missouri. The Society’s call numbers follow the citations in brackets.

Articles from the Missouri Historical Review

- Hall, Thomas B. “John Sappington.” v. 24, no. 2 (January 1930), pp. 177-199.

- Morrow, Lynn. “Dr. John Sappington: Southern Patriarch in the New West.” v. 90, no. 1 (October 1995), pp. 38-60.

Articles from the Newspaper Collection

- “Historic old home of John W. [sic] Sappington at Arrow Rock.” Columbia Missourian. August 29, 1924. p. 4, c. 3. [Reel # 7592]

- “History of the Sappington fund and how it is used by Saline County.” Columbia Missourian. July 19, 1926. p. 4, c. 4. [Reel # 7600]

- “Sappington proposes founding of a Manual Labor School in Missouri.” Jefferson Enquirer. December 11, 1847. p. 3, c. 1. [Reel # 16350]

- “Sketch of Dr. John Sappington and his family.” Columbia Missourian. November 1, 1924. p. 1, c. 2. [Reel # 7593]

Books and Articles

- Christensen, Lawrence O., William E. Foley, Gary R. Kremer, and Kenneth H. Winn, eds. Dictionary of Missouri Biography. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1999. pp. 666-667. [REF F508 D561]

- Hall, Thomas B., Jr. Dr. John Sappington of Saline County, Missouri. Arrow Rock, Mo.: Friends of Arrow Rock, 1975. [F508.1 Sa69h3]

- Morrow, Lynn. John Sappington: Southern Patriarch in the New West. Columbia, Mo.: Lynn Morrow, 1985. [F508.1 Sa69m]

- Sappington, John, and Ferdinando Stith. The Theory and Treatment of Fevers. Arrow Rock, [Mo.]: J. Sappington, 1844. [F567 Sa69]

Manuscript Collection

- Sappington Family Papers, 1819-1895 (C0159)

Papers of Dr. John Sappington of Arrow Rock, MO, and his family. Business letters about Sappington’s pills and book for the treatment of malaria. Letters and papers from family and friends; supplies; notes. Legal case of Coffee & Blacke vs. Sappington & Sons. Miscellaneous personal record and account book. - Sappington Family Papers, 1831-1939 (C2889)

Copies of miscellaneous papers of Dr. John Sappington of Arrow Rock, MO, and his family. A few personal papers, household accounts, and records of his pill business, but mostly material about the financial provisions Sappington made for the children of his daughter Eliza and Alonzo Pearson. - John Sappington Papers, 1803-1887 (C1027)

Correspondence and miscellaneous papers, largely concentrating on Sappington’s anti-fever medicine business. Also correspondence and papers of William B. Sappington, Erasmus D. Sappington, and Claiborne Fox Jackson.

Outside Resources

These links, which open in another window, will take you outside the Society’s website. The Society is not responsible for the content of the following websites:

- Dr. John Sappington Memorial Museum

The Friends of Arrow Rock maintain a museum in honor of Dr. John Sappington at Arrow Rock. The village is a National Historic Landmark.