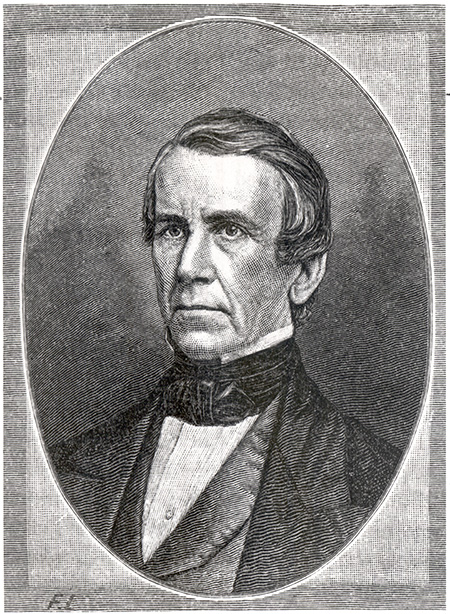

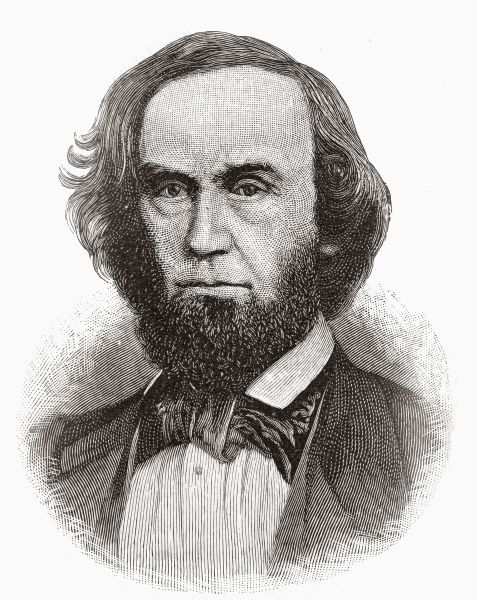

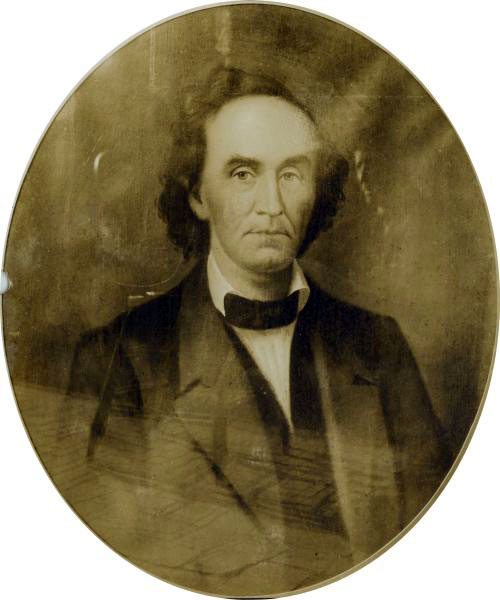

Claiborne Fox Jackson

Introduction

During the early period of Missouri’s state history, Democrat Claiborne Fox Jackson served as speaker in the state House of Representatives. He vigorously supported proslavery positions and making Texas a state. Jackson was elected governor in 1860 and soon after assuming office worked to take Missouri out of the Union.

Early Years

Claiborne Fox Jackson was born in Kentucky on April 4, 1806, to Dempsey and Mary Jackson. The Jacksons were prosperous tobacco farmers and enslaved numerous people. During his boyhood, young Claiborne received some educational instruction.

In 1826, not long after Missouri became a state, Jackson traveled to the central part. He settled in Franklin, where the Santa Fe Trail began. The establishment of the trail opened up a prosperous trade with Mexico. Despite poor economic times elsewhere, the town was a growing, thriving, and bustling community. Jackson and his older brothers established a mercantile store in the affluent town. Many of the first immigrants who settled in this region came from the South. They brought the people they enslaved and established small and large farms along the Missouri River.

Jackson Joins the Militia

In 1832 Jackson joined the Howard County militia and was elected by its volunteers to lead them during the Black Hawk War. Black Hawk was the leader of the Sac and Fox tribes, many of whom had been forced to leave their traditional territory in northern Illinois in 1804. Some, however, refused to leave permanently. After another treaty agreement was forced upon the Sac and Fox in 1831, Black Hawk led a band from Iowa country into northern Illinois. The military operations against the Sac and Fox tribes ended in their defeat.

Jackson soon returned to civil life and moved west a short distance from Franklin across the Missouri River to Arrow Rock, where he married one of John S. Sappington’s daughters.

Sappington became famous and wealthy for his development and sale of quinine pills, which were an effective cure for malaria. Jackson benefited both financially and politically from his marriage. His father-in-law had important connections to prominent members of the Democratic Party.

A Career in Politics

In 1836 the people of Saline County elected Jackson to the state House of Representatives. After the term, he moved to Fayette, the seat of Howard County and an important center of Democratic political power in Missouri. For a time, Jackson worked at the Fayette branch of the state bank and developed important political alliances, which proved invaluable to him later.

In 1840 Jackson became involved in a dispute with John B. Clark, the Whig Party nominee for governor. Both men resided in Fayette. The controversy began when Jackson anonymously published an editorial in a local paper accusing Clark of election fraud. The dispute led to Clark challenging Jackson to a duel, but the matter was resolved without bloodshed. Eventually, the two men became political allies after Clark switched to the Democratic Party.

The voters of Howard County returned Jackson to the state house in 1842. A strong supporter of slavery, he soon became a leader in the legislature. He was also a member of what came to be known as the “Central Clique,” an unofficial organization that sometimes made important policy and nomination decisions for Missouri’s Democratic Party. By this time Jackson had accumulated considerable wealth and devoted much of his time to politics.

During the 1844 campaign, Missouri’s Democratic Party was split over the issue of making Texas a state, which was then an independent country. The issue was known as the annexation question. Many Democrats, including U. S. Senator Thomas Hart Benton, and almost all Whigs opposed annexation as dangerous. They believed it would endanger the Union by agitating the slavery issue and possibly provoking war with Mexico. Jackson, who supported annexation, at first opposed Benton’s reelection. However, the Democrats worked out a compromise in which Benton agreed to annexation “at the earliest practicable moment.” In return they would support his candidacy.

Speaker of the House

In 1844 the state house elected Jackson as its speaker. He presided over a turbulent session marked by infighting among its Democratic members. Among the many disputes, serious splits developed over several issues in particular. They were a resolution instructing Missouri’s congressmen to vote for the annexation of Texas, a bill to reduce the pay of Missouri’s governor and judges, and legislation to make representation more equal in the General Assembly.

This latter bill angered those who wanted to maintain the advantage then held by rural Missourians over the more densely populated regions of the state. Even though it was unfair, many Democrats opposed reforming the system of representation because the law benefited their party.

Speaker Jackson, however, was from a populous region and favored a more fair system of representation. When it came time to appoint members to a committee to reconcile the house and senate bills, some Democratic members feared that Jackson would appoint members opposed to the house bill. To prevent this, some members moved to elect committee members on the house floor.

Because this had never happened before and reflected upon his leadership, Jackson resigned as speaker. He was soon reelected unanimously. Ironically, Hamilton R. Gamble, a Whig member of the house and later his firm opponent during the Civil War, renominated Jackson. After Jackson’s reelection, Gamble was one of three members sent to notify him.

Jackson and the Issue of Slavery

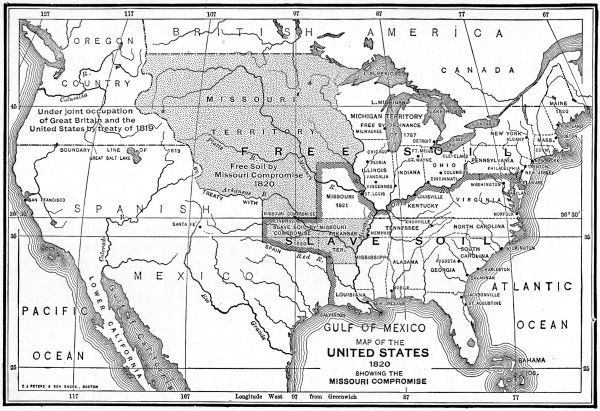

In 1821 Missouri had entered the United States as a slave state as part of the Missouri Compromise. After the United States acquired new territories from Mexico at the end of the Mexican War in 1848, debate over the future of slavery again became an important issue. Would these new lands be slave or free? Senator Benton’s forceful opposition to the further extension of slavery again brought him into direct conflict with the South and many Missourians. Led by Jackson, in 1848 Missouri’s General Assembly passed a series of measures called the Jackson Resolutions. The measures opposed Benton and asserted that Congress had no power to limit or prohibit slavery in the territories. These resolutions also instructed Missouri’s representatives in Washington DC to support the extension of slavery into the territories.

After Jackson and other proslavery leaders of the Democratic Party in Missouri opposed him, Benton failed to gain reelection in 1850. Instead, for the first time, the General Assembly elected a member of the Whig Party, Henry S. Geyer, a prominent lawyer. Jackson also suffered political repercussions, however, for Benton’s supporters prevented his nomination to Congress in both 1853 and 1855. During this period, Missouri Democrats, indicating the split in their party, referred to themselves as either Benton or anti-Benton Democrats.

Jackson Becomes Governor

While he held no elected office in the 1850s, Jackson remained deeply involved in politics as chairman of the Democratic Central Party and worked to mend the split in the party between Benton’s supporters and opponents. Through this position and his contacts, Jackson plotted to gain political office again. In 1860 he won the Democratic nomination for governor running as a moderate.

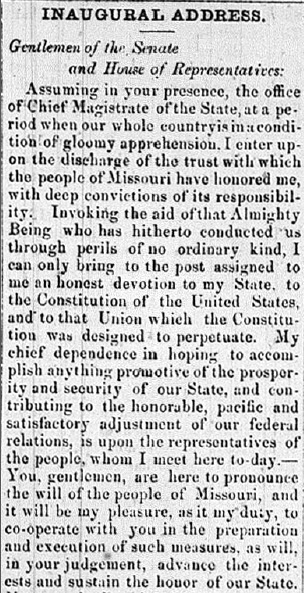

After Lincoln’s election, Jackson, despite having presented himself during the campaign as a supporter of the Union, immediately pushed for secession. In his inaugural speech as governor, he made clear his determination to support the South.

A majority of Missouri’s voters rejected secession, however, and elected to a state convention only delegates who favored remaining in the Union. This result surprised Jackson and others supporting secession. Up to this point, February 18, 1861, state legislators had been willing to arm and prepare for war.

Undaunted, Jackson tried to persuade the legislators to pass a military bill, but he was unsuccessful. The convention delegates rejected secession and called for Missouri to act as a neutral to mediate between the North and the South in the hope of avoiding war.

The Civil War

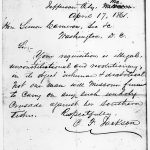

After this, Jackson secretly tried to achieve what he could not do openly through the political process. First, he rejected President Lincoln’s call for troops from Missouri. Later, he communicated with President Jefferson Davis and other Confederate representatives to coordinate efforts. Jackson also sought to prepare the state militia for conflict and hoped soon to seize weapons at the St. Louis Arsenal. After federal commander Nathaniel Lyon captured a militia training camp near St. Louis, incidentally named for Governor Jackson, both Unionists and Secessionists quickly prepared for war.

To buy time, Jackson met with Lyon and Congressman Frank Blair Jr., but Lyon made it clear that the time for negotiations was over. Jackson then called for 50,000 state volunteers for the militia. In response, Lyon led forces from St. Louis and captured Jefferson City, the state capital. Jackson and his supporters, including most of the state legislature, however, had fled before Lyon’s arrival. The state convention then passed measures removing Jackson from office. They replaced him with Hamilton R. Gamble, who served as Missouri’s provisional governor for more than two years.

In August 1861 Jackson met in Richmond, Virginia, with Confederate President Jefferson Davis and gained support for Missouri’s Confederate army under Sterling Price’s command. He arranged for treaty negotiations between the state and the Confederate government. Jackson also convened the ousted legislature, despite its legality being in doubt, to meet and pass a bill of secession. In late 1861 Jackson left Missouri never to return alive. He died of cancer at Little Rock, Arkansas, on December 6, 1862. His body was buried in a cemetery in Arrow Rock, Missouri.

Jackson's Legacy

Jackson’s career was similar to that of many state politicians of his period. As a Southerner, it seems he never questioned the morality of slavery and strongly condemned those who did. Jackson worked for Missouri’s secession from the Union and therefore shared responsibility for the great destruction of property and loss of life that occurred in the state during the Civil War.

Text and research by Dennis Boman

References and Resources

For more information about Claiborne Fox Jackson’s life and career, see the following resources:

Society Resources

The following is a selected list of books, articles, and manuscripts about Claiborne Fox Jackson in the research centers of The State Historical Society of Missouri. The Society’s call numbers follow the citations in brackets.

Articles from the Missouri Historical Review

- Lyon, William H. “Claiborne Fox Jackson and the Secession Crisis in Missouri.” v. 58, no. 4. (July 1964), pp. 422-441.

- Phillips, Christopher. “Calculated Confederate: Claiborne Fox Jackson and the Strategy for Secession in Missouri.” v. 94, no. 4. (July 2000), pp. 389-414.

Articles from the Newspaper Collection

- “Death of Gov. Jackson Confirmed.” Liberty Weekly Tribune. January 16, 1863. p. 2, c. 3. [Reel # 26664]

- “Gov. Jackson’s Reply to the Call for Troops.” Liberty Weekly Tribune. April 26, 1861. p. 1, c. 6. [Reel # 26663]

- “Governor’s Proclamation.” Liberty Weekly Tribune. June 21, 1861. p. 4, c. 1. [Reel # 26663]

- “Inaugural Address.” Liberty Weekly Tribune. January 18, 1861. p. 1, c. 3. [Reel # 26663]

- “A Secession Candidate.” Liberty Weekly Tribune. May 4, 1860. p. 2, c. 1. [Reel # 26663]

- “Sketch of C.F. Jackson of Howard.” Liberty Weekly Tribune. March 14, 1851. p.1, c. 6. [Reel # 26659]

Books and Articles

- Christensen, Lawrence O., William E. Foley, Gary R. Kremer, and Kenneth H. Winn, eds. Dictionary of Missouri Biography. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1999. pp. 423-426. [REF F508 D561]

- Phillips, Christopher. Missouri’s Confederate: Claiborne Fox Jackson and the Creation of Southern Identity in the Border West. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2000. [REF F508.1 J1325]

- Snead, Thomas L. The Fight for Missouri: From the Election of Lincoln to the Death of Lyon. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1886. pp. 17, 21-25, 66-67. [REF F554.1 Sn21]

Manuscript Collection

- John Sappington Papers (C1027)

This collection contains correspondence and miscellaneous papers, largely concentrating on Sappington’s anti-fever medicine business. Also included are the correspondence and papers of Claiborne Fox Jackson.

Outside Resources

These links, which open in another window, will take you outside the Society’s website. The Society is not responsible for the content of the following websites:

- Missouri State Archives: Claiborne Fox Jackson, 1861

This digital collection is part of Missouri Digital Heritage and contains records from Jackson’s term as governor.