The Chouteau Brothers

Introduction

Auguste Chouteau helped his foster father, Pierre Laclède Liguest, found the city of St. Louis. Auguste and his half-brother, Pierre, became successful fur traders, businessmen, and government officials. During their lifetime, the Chouteaus were the most prominent and powerful family in St. Louis. They helped make St. Louis a thriving commercial center.

Early Life and Education

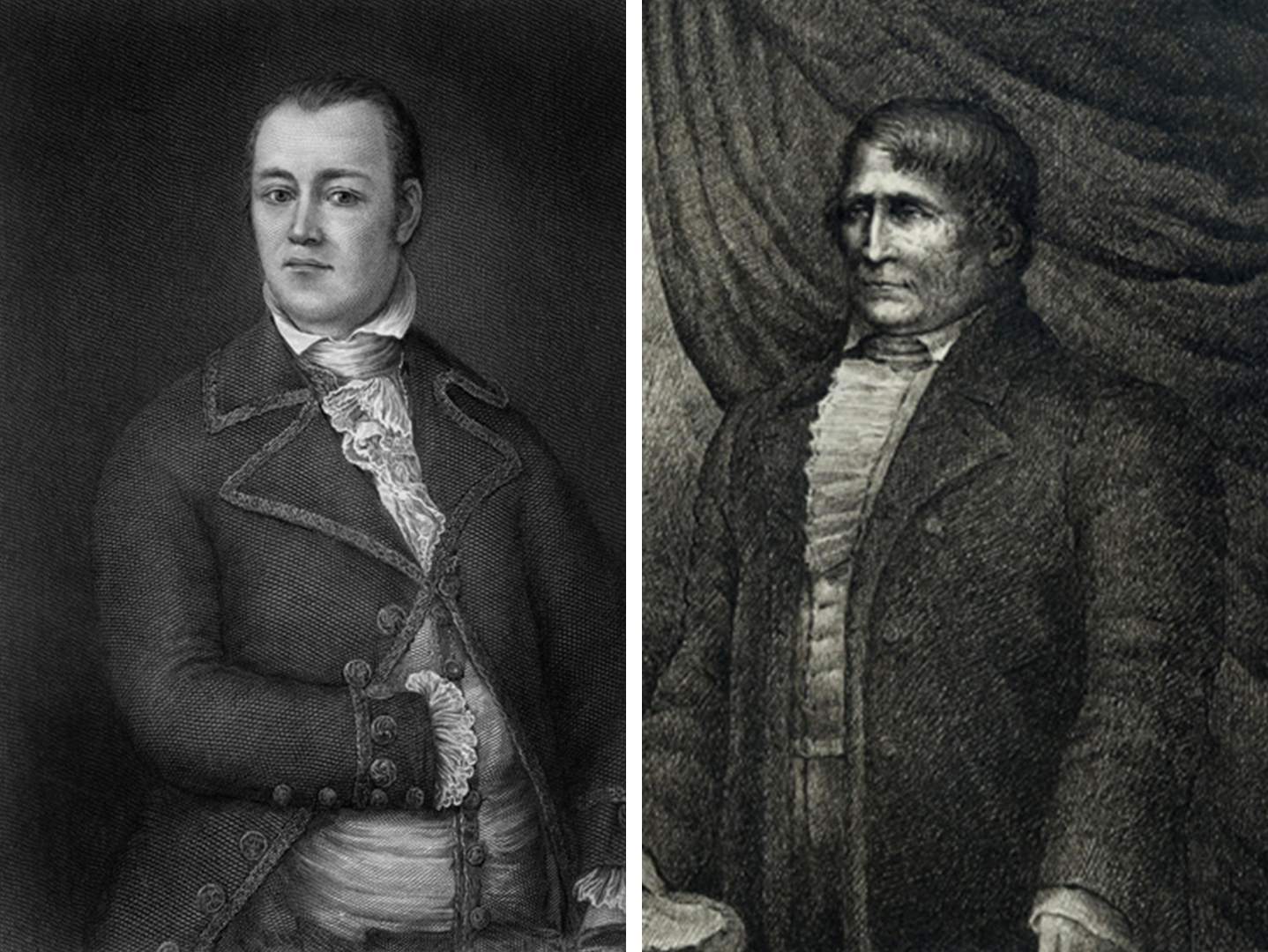

René Auguste Chouteau (called Auguste) was born in New Orleans on either September 7, 1749, or September 26, 1750, to Marie Thérèse Bourgeois Chouteau (known as Madame Chouteau) and her husband, also named René Auguste Chouteau, a baker and tavern owner. René Chouteau abandoned his wife and son sometime before 1755, the year that Pierre de Laclède Liguest (known as Laclède) emigrated from France to the New Orleans, in the French territory of Louisiana. Laclède and Madame Chouteau fell in love, but could not marry because of her previous marriage to René (the Catholic Church and New Orleans law forbade divorce). On October 10, 1758, Laclède and Madame Chouteau had a son, Jean Pierre (called Pierre). Between 1760 and 1764, they had daughters Marie Pelagie, Marie Louise, and Victoire. Since Laclède and Madame Chouteau were unmarried, all of their children were baptized under the name of Chouteau, as if Madame Chouteau’s estranged husband was their father.

Auguste likely attended school in New Orleans. Laclède was Auguste’s mentor and father figure. Both shared a lifelong love of reading and each owned a large library. Since Pierre was not yet six when he moved to the frontier village of St. Louis, he received a less formal education. Both Auguste and Pierre learned penmanship and a number of other skills, such as bookkeeping and surveying. Laclède joined a local military regiment and eventually became the business partner of his regimental commander, Gilbert Antoine de St. Maxent, a prominent fur trader. Laclède and Maxent eventually employed Auguste as a clerk, but his role in their business operations was soon to expand greatly.

Building St. Louis

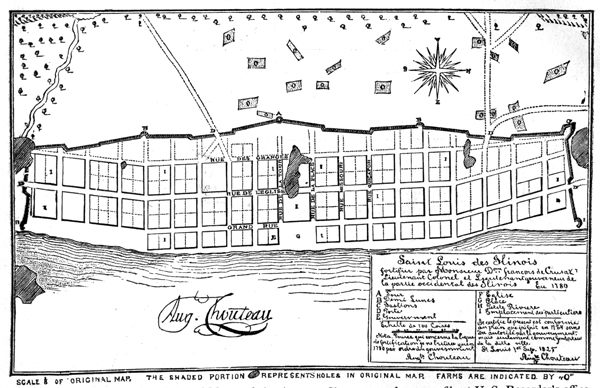

Amid financial problems caused by the French and Indian War, the governor of Louisiana gave Maxent and Laclède permission in 1762 to build a trading post several hundred miles upriver from New Orleans. They were also granted a monopoly on trade with indigenous tribes west of the Mississippi River. Accompanied by the thirteen-year-old Auguste, Laclède departed in August 1763 with about thirty workmen, some enslaved individuals, and a large collection of supplies on five boats.

Laclède located a promising spot south of the confluence of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers, then spent the winter in Fort Chartres, a French fort on the other side of the river. He sent Auguste ahead to start building a small settlement and trade depot. Auguste likely reached what is now the St. Louis riverfront on February 15, 1764, with a detachment of workers and supplies, and immediately began clearing land and erecting buildings. Laclède rejoined Auguste and his workers in the spring, with detailed building plans for the settlement he named St. Louis, after King Louis IX of France. They were soon joined by several other French colonists. In September, Madame Chouteau, Pierre, and the rest of the Chouteau children joined Laclède and Auguste in St. Louis.

The Secret to Their Success

Laclède and Maxent lost their trade monopoly when the French were forced to give their colonial holdings west of the Mississippi to Spain after the French and Indian War. Laclède went bankrupt after going into debt to buy out Maxent’s share of their partnership, then became ill and died in 1778. Auguste and Pierre went on to make a fortune in the fur trade. One reason for their success was their close relationship with local indigenous tribes.

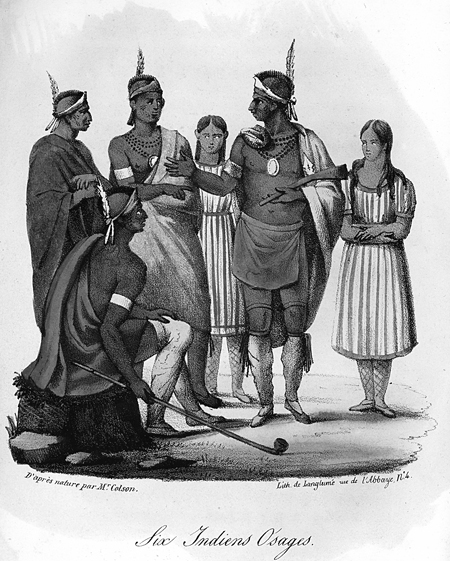

Before Laclède’s death, Auguste began a partnership with Pierre in the St. Louis fur trade. Since the valuable furs they sought were obtained by trade with Native Americans, Laclède taught Pierre and Auguste the importance of having good relations with the tribes that supplied their furs, particularly the powerful Osage tribe. The brothers took this lesson to heart, and it was the key to their financial success. Auguste and Pierre became students of indigenous culture. They were respectful of tribal customs and developed a reputation for being honest and fair. The Chouteaus were also known for providing a variety of high-quality goods to tribes that supplied them with furs. This reputation helped the Chouteaus succeed despite competition from other traders.

Pierre and Auguste even had family connections to indigenous tribes. Pierre lived in an Osage village as a teenager, and it is believed that as young men both he and Auguste had Native American wives. Auguste fathered four children with Native American women, and although it is unknown whether Pierre had any Native American children, many of his sons did.

Powerful Connections

Aside from their bonds with the Osages, another key to the Chouteau brothers’ success was their connections with several of the richest and most powerful people in the Louisiana Territory. They had a close relationship with Gilbert Maxent, Laclède’s former business partner, one of the most well-connected merchants in New Orleans. They also gained powerful connections through marriage. In 1786, Auguste married Marie Thérèse Cerré, the daughter of a rich merchant. In 1783, Pierre married Pelagie Kiersereau, an heiress to a small fortune. After Pelagie died during childbirth in 1793, Pierre married Brigitte Saucier. She had three brothers who were successful merchants. Aside from his Native American children, Auguste had seven children by his wife Marie Thérèse. Pierre had four children with his first wife and five more with his second wife. Almost all of Auguste and Pierre’s male children were successful businessmen and/or fur traders, and nearly all of their daughters married powerful and prominent men such as merchants, government officials, and military officers.

The brothers maintained a good relationship with the Spanish government. When the American Revolutionary War disrupted trade along the Mississippi, only Auguste and a few other merchants were given special permission to buy goods across the river in British territory. When Spain sided with the Americans against Britain, Auguste donated a large amount of money to help the Spanish military build defenses in St. Louis. Auguste and Pierre both served in the local militia that successfully defended the city against an attack from British soldiers and their indigenous allies on May 26, 1780.

When the relationship between the Osages and the Spanish government declined in the late 1780s and early 1790s, it resulted in a trade ban and, eventually, a declaration of war. The Chouteaus helped draft a peace agreement between the two sides. As part of the agreement, the brothers built Fort Carondelet in 1795 deep in Osage territory, in what is now western Missouri. Pierre was given the militia rank of lieutenant and paid by the Spanish to run the fort. The Chouteaus were then given a monopoly on trade with the Osage for several years. The brothers also invested in real estate, milling, banking, mining, and retail stores.

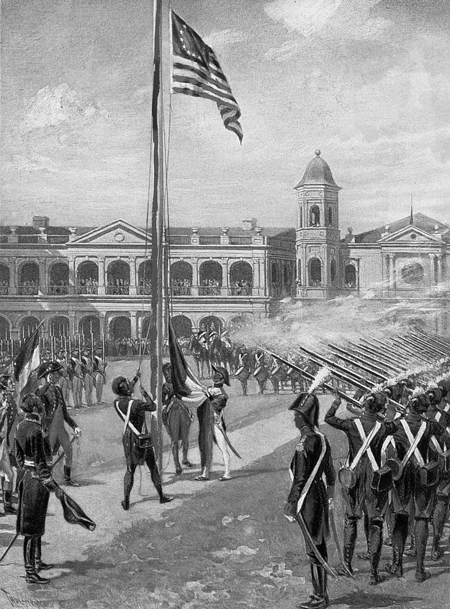

Becoming American

When the United States purchased the Louisiana Territory in 1803, the Chouteaus pursued the same kind of relationship with America that they had held with Spain. They shared their knowledge of the region and provided money, lodging, and supplies to aid Lewis and Clark‘s Corps of Discovery expedition. Auguste and Pierre communicated regularly with President Thomas Jefferson, and Pierre led a delegation of indigenous tribal leaders to meet him.

The Chouteau brothers served in a number of government offices after the Americans took over. Auguste was appointed as a judge, justice of the peace, pension agent for Missouri veterans of the Revolutionary War, lieutenant colonel of the first American militia group west of the Mississippi, and served in the Missouri territorial legislature. Pierre was a justice of the peace and served as a militia officer. Pierre was also named the head Indian agent for Upper Louisiana. He helped negotiate the Treaty of Fort Clark, which required the Osage to give up most of their land in Missouri and Arkansas.

In 1805, Marguerite, who was enslaved by Pierre, sued for her freedom. When the Spanish outlawed indigenous slavery in 1769, Marguerite’s mother, who was Natchez, should have been freed. Instead, she remained enslaved and her children, including Marguerite, were born into slavery. Although Marguerite lost the case, mainly due to Pierre’s political influence in St. Louis, she filed another freedom suit in 1825. In 1836 she won her freedom from Pierre, and the freedom of all her sisters and children. This case is credited with officially ending indigenous slavery in Missouri.

Death and Legacy

Auguste and Pierre remained leading citizens in St. Louis for the rest of their lives. By the early 1820s, Auguste’s health was declining. He died after a long illness on February 13, 1829, at the age of seventy-nine. Auguste was the richest man in St. Louis at the time of his death. His estate was valued at over $100,000, which today would be worth millions. It included several enslaved individuals, real estate, an impressive library, and many personal items. Around the time of Auguste’s death, Pierre retired from business and began limiting his public appearances in St. Louis. Pierre died on July 9, 1849, at the age of ninety. His estate was valued at over $79,000.

Auguste and Pierre Chouteau were pioneers in the fur trade and leading citizens of St. Louis. Auguste helped carve the settlement out of the wilderness, and the two brothers’ business activities helped make St. Louis an important trade center on the Mississippi River. Their many investments, their good relationship with local indigenous tribes, and their favor with the Spanish and American governments helped bring long-term success not only to generations of their descendants but also to the city of St. Louis.

Text and research by Todd Barnett

References and Resources

For more information about Auguste and Pierre Chouteau’s life and career, see the following resources:

Society Resources

The following is a selected list of books, articles, and manuscripts about Auguste and Pierre Chouteau in the research centers of The State Historical Society of Missouri. The Society’s call numbers follow the citations in brackets.

Articles from the Missouri Historical Review

- Brownlee, Richard S., ed. “Settling Upper Louisiana Territory.” v. 70, no. 4 (July 1976), pp. 386-392.

- Foley, William E. “The Lewis and Clark Expedition’s Silent Partners: The Chouteau Brothers of St. Louis.” v. 77, no. 2 (January 1983), pp. 131-146.

- Foley, William E. “Slave Freedom Suits before Dred Scott: The Case of Marie Jean Scypion’s Descendants.” v. 79, no. 1 (October 1984), pp. 1-23.

- Foley, William E., and Charles David Rice. “Pierre Chouteau, Entrepreneur as Indian Agent.” v. 72, no. 4 (July 1978), pp. 365-387.

- Goodrich, James W., and Lynn Wolf Gentzler, eds. “‘I Well Remember’: David Holmes Conrad’s Recollections of St. Louis, 1819-1823, Part 1.” v. 90, no. 1 (October 1995), pp. 1-37.

- Penn, Dorothy, ed. “The Missouri Reader: The French in the Valley, Part 1.” v. 40, no. 1 (October 1945), pp. 90-122.

- Rickey, Don, Jr. “The Old St. Louis Riverfront, 1763-1960.” v. 58, no. 2 (January 1964), pp. 174-190.

Books and Articles

- Ames, Gregory P., ed. Auguste Chouteau’s Journal: Memory, Mythmaking & History in the Heritage of New France. St. Louis: St. Louis Mercantile Library, University of Missouri-St. Louis, 2010. [REF H235.47 C459 2010]

- Chouteau, Auguste. Fragment of Col. Auguste Chouteau’s Narrative of the Settlement of St. Louis: A Facsimile Edition of the First Printing of a Translation from the Original French Manuscript in the Collection of the St. Louis Mercantile Library. St. Louis: St. Louis Mercantile Library Association, 1989. [REF H235.47 C459]

- Christian, Shirley. Before Lewis and Clark: The Story of the Chouteaus, the French Dynasty that Ruled America’s Frontier. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2004. [REF F508.2 C459ch]

- Cunningham, Mary B. The Founding Family of St. Louis. St. Louis: Midwest Technical Publication, 1977. [REF F508.2 C459c In Case]

- “Date of St. Louis’ Founding Disputed.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. February 14, 2010. [REF Vertical File]

- Fausz, Frederick J. Founding St. Louis: First City of the New West. Charleston, SC: History Press, 2011. [REF H235.47 F275]

- Foley, William E. “The Laclede-Chouteau Puzzle: John Francis McDermott Supplies Some Missing Pieces.” Gateway Heritage. v. 4, no. 2 (Fall 1983), pp. 18-25. [REF F550 M69gh]

- Foley, William E., and C. David Rice. The First Chouteaus: River Barons of Early St. Louis. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1983. [REF F508.2 C459f]

- “The Founding of the City.” St. Louis Globe-Democrat. December 11, 1963. [REF Vertical File]

- Hurt, Douglas A. “Brothers of Influence: Auguste and Pierre Chouteau and the Osages before 1804.” Chronicles of Oklahoma. v. 78, no. 3 (Fall 2000), pp. 260-277. [REF 976.6 C468]

- “Laclede, not Chouteau, Was the Founder of St. Louis. A Survey of Documentary Evidence.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. November 27, 1922. [REF Vertical File]

- McDermott, John Francis, ed. The Early Histories of St. Louis. St. Louis: St. Louis Historical Documents Foundation, 1952. [REF H235.47 M143]

- “Pierre Laclede Was Founder of St. Louis, Father Kenny Says.” St. Louis Star. September 11, 1922. [REF Vertical File]

- Westbrook, Harriette Johnson. “The Chouteaus and Their Commercial Enterprises.” Chronicles of Oklahoma. v. 11, no. 3 (June 1933), pp. 787-797, 942-966. [REF 508.2 C459]

- “Who Really Founded St. Louis—Laclede or Chouteau?” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. September 4, 1922. [REF Vertical File]

Manuscript Collection

- Breckenridge, William Clark (1862-1927) Papers, 1752-1927 (C1036)

The papers of this St. Louis businessman, writer, and historian contain correspondence, scrapbooks, book sale announcements, and miscellaneous materials with an emphasis on St. Louis and Missouri history. Volumes 3, 7, and 9 of this collection contain newspaper clippings related to the Chouteau family. - Corby Family Papers, 1804-1905 (C0086)

Folder 4 of this St. Joseph pioneer family’s papers contains several letters written in French, including one signed by Auguste Chouteau. - Dickmann, Bernard F. (1888-1971), Papers, 1895-1980 (C3403)

Bernard F. Dickmann was the mayor of St. Louis. Several materials related to the commemoration of St. Louis history are included in this collection. References to Auguste and Pierre Chouteau appear in various materials in folders 2, 61, 70, 73, 77, and 90. - Missouri, St. Charles, Papers, 1801-1831 (C1566)

This collection includes a letter from Jean B. Belland to Auguste Chouteau concerning a ferrying bill. - State Historical Society of Missouri, Typescript Collection (C0995)

Items 220 and 707 in this microfilm collection have material related to the Chouteau family, including a copy of Auguste Chouteau’s journal. - U.S. States of the United States, Records, Missouri, 1762-1870 (C2968)

Roll 1 in Unit 1 of this microfilm collection includes Auguste Chouteau’s journal describing the founding of St. Louis. It is written in French. - U.S. Superintendency of Indian Affairs, St. Louis, Records, 1807-1855 (C2969)

The records contain correspondence, account books, and treaties with various Indian tribes. Much of the material is to and from Indian agents at the area agencies. The bulk of the material is from the period when William Clark was superintendent. Also included are records of the Missouri Fur Company, 1812-1817. Volume 30 contains the signatures of Pierre and Auguste Chouteau.

Outside Resources

These links, which open in another window, will take you outside the Society’s website. The Society is not responsible for the content of the following websites:

- Auguste Chouteau Papers (M-022)

Digital copies of the journal fragments of Auguste Chouteau’s “Narrative of the Settlement of St. Louis,” including English translation, can be found at this webpage from the Mercantile Library at the University of Missouri-St. Louis. - St. Louis Circuit Court Records

This website from the St. Louis Circuit Court Historical Records Project provides descriptions and digital scans of case records relating to freedom suits filed by slaves in the city of St. Louis. This includes the case Marguerite filed against Pierre Chouteau. - Virtual Museum of New France

This website contains information about New France, the greater colony of which Upper Louisiana was a part.