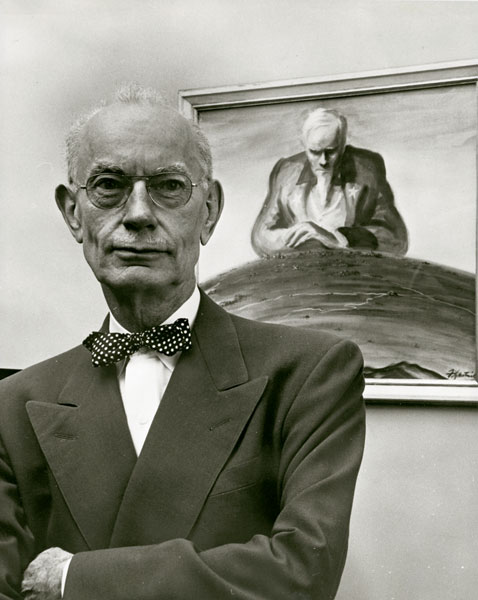

Daniel R. Fitzpatrick

Daniel Robert Fitzpatrick was one of the most important editorial cartoonists in the United States. He was born in Superior, Wisconsin, on March 5, 1891, to Patrick and Delia Ann Clark Fitzpatrick.

As a young man, Fitzpatrick dropped out of high school. He later said he left school because his love of history was not encouraged. When his mother discovered that he had dropped out, she asked, “What do you think you’re going to grow up to be?” Fitzpatrick retorted, “An editorial cartoonist.”

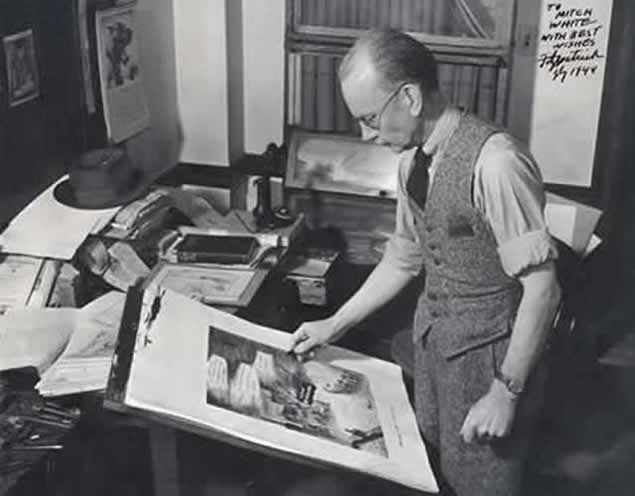

He studied anatomy and life drawing for two years at the Art Institute of Chicago before getting his first cartooning job at the Chicago Daily-News. In 1913 he married Lee Ann Dressen, and then took a job at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch where he remained until his retirement in 1958.

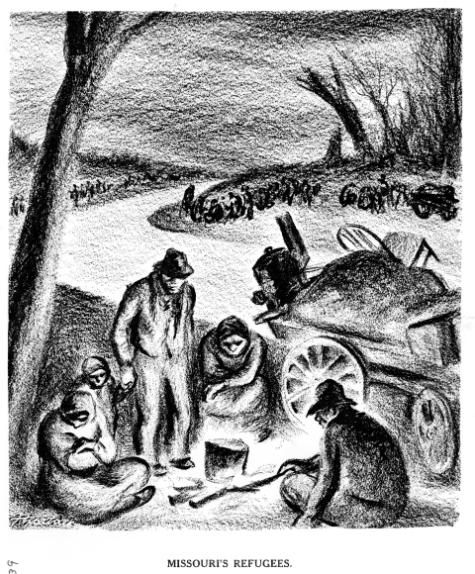

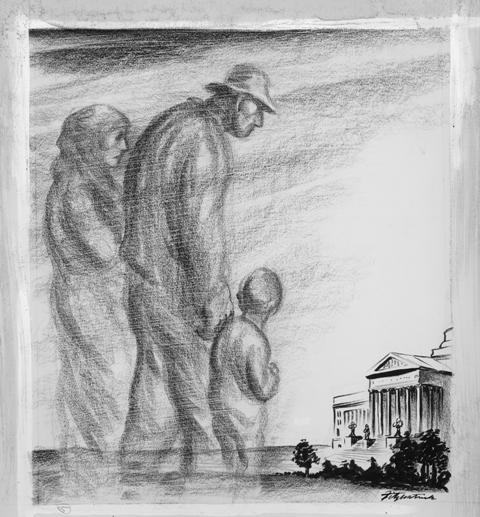

Universally acknowledged as the dean of editorial cartoonists, “Fitz” strongly supported the rights of the underdog while attacking the conservative “establishment.” Through cartoons with messages on equal rights for women and blacks, a clean environment, and concern for the militarization of America’s post-World War II foreign policies, he gained the admiration and respect of scholars, journalists, statesmen, and regular newspaper readers worldwide.

Fitzpatrick, never one to shy away from controversial subjects, earned the ire of a Missouri judge for a cartoon that chastised the courts after a criminal case against an alleged extortionist was dismissed. Fitzpatrick and Ralph Coghlan, editor of the Post-Dispatch editorial page, were fined and sentenced to jail for contempt of court. The decision was later reversed on appeal to the Missouri Supreme Court.

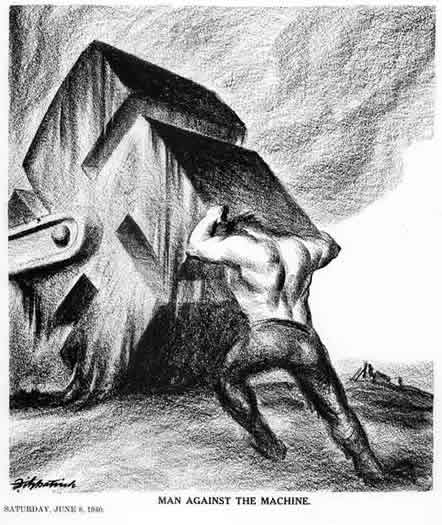

As Adolph Hitler rose to power in Germany during the 1930s, Fitzpatrick anticipated a second world war. In response, he created powerful cartoons that often depicted the threat of Hitler’s Nazi war machine in the form of a giant swastika rolling across Europe. His sophisticated and forceful use of imagery helped turn American public opinion against Hitler and Nazi Germany.

On the domestic front, Fitzpatrick challenged Kansas City political boss Tom Pendergast’s control of Missouri politics in a series of bold and provocative cartoons. The artist brought a similar awareness to political corruption in St. Louis through his “Rat Alley” series.

Fitzpatrick’s success was not only the result of his own creative genius; he also had the support of Post-Dispatch publisher and editor Joseph Pulitzer Jr. Fitzpatrick and Pulitzer agreed that the artist would not have to draw editorial cartoons that differed from his own personal beliefs. This allowed Fitzpatrick to take special leave from the newspaper when the Post-Dispatch supported presidential candidate Alf Landon over Franklin D. Roosevelt and Thomas E. Dewey over Harry S. Truman.

During his lengthy career, Fitzpatrick’s cartoons were syndicated in thirty-five newspapers in the United States. He won the Pulitzer Prize for editorial cartooning in 1926 and 1955.

Aware of his contribution to twentieth-century history, Fitzpatrick donated 1,750 original drawings to The State Historical Society of Missouri in 1946.

Daniel Fitzpatrick died after a long illness on May 18, 1969, in St. Louis, Missouri. His body was given to the Washington University School of Medicine. Fitzpatrick’s artwork continues to inspire new generations of editorial cartoonists.

Text and research by Kimberly Harper and Joan Stack

References and Resources

For more information about Daniel Robert Fitzpatrick’s life and career, see the following resources:

Society Resources

The following is a selected list of books, articles, and manuscripts about Daniel R. Fitzpatrick in the research centers of The State Historical Society of Missouri. The Society’s call numbers follow the citations in brackets.

Art Collection

- The State Historical Society of Missouri Editorial Cartoon Collection

The Society’s collection of editorial cartoons was started in 1946 with an important donation of works by Pulitzer-prize-winning artist Daniel R. Fitzpatrick. The collection continues to grow with over 21,000 works from Bill Mauldin, Tom Engelhardt, and many others. The works graphically and often poignantly reflect the attitudes and opinions of the artists and the citizens of Missouri from the early days of the twentieth century through World War I, the Great Depression, World War II, and later events that saw the United States develop into a world leader.

Articles from the Missouri Historical Review

- Yeshilda, Susan. “Daniel R. Fitzpatrick: A Missouri Cartoonist.” v. 83, no. 2 (January 1989), pp. 177-186.

Books and Articles

- “Cartoonist Daniel R. Fitzpatrick Dies; Two-Time Pulitzer Prize-Winner.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Undated. [REF Vertical File]

- “D.R. Fitzpatrick Will Retire Aug. 1” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. June 25, 1958. [REF Vertical File]

- “Daniel R. Fitzpatrick Dies; Noted Cartoonist.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. May 19, 1969. [REF Vertical File]

- Dunne, Gerald T. “In Durance Vile—A Case of Court-Press Conflict!” The Missouri Supreme Court Historical Journal. v. 1, no. 4 (Winter 1987), pp. 1-7. [REF Vertical File]

- Fitzpatrick, Daniel. As I Saw It: A Review of Our Times. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1953. [SHS REF 741.5 F582a]

- “Marks, Robert. “Crusader with a Crayon.” Coronet. v. 17, no. 3 (January 1945), pp. 36-41. [REF Vertical File]

- Pogel, Nancy. “Fitzpatrick, Daniel Robert.” Dictionary of American Biography. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1988. [REF 920 D561 Supplement 8]

Manuscript Collection

- Daniel R. Fitzpatrick Cartoons (C0820)

Newspaper cartoons concerned with Missouri politics during this period. Published in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

- Daniel R. Fitzpatrick Papers (C3832)

The Fitzpatrick Papers contain the personal and business correspondence of Daniel R. Fitzpatrick, editorial cartoonist for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. The collection also contains magazines and newspaper articles concerning “Fitz’s” cartoons of local, regional, and national politics, including government propaganda for both World Wars. Sixteen one-half hour television documentaries on political affairs, entitled Forty-five Years with Fitzpatrick are included in the collection.

Outside Resources

These links, which open in another window, will take you outside the Society’s website. The Society is not responsible for the content of the following websites:

- St. Louis Post-Dispatch FBI Files Archive

This website contains a collection of newspaper clippings from the FBI related to the Post-Dispatch and Fitzpatrick’s contempt of court case.