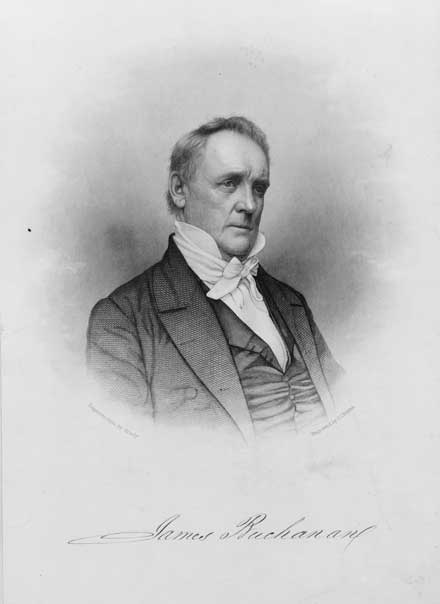

John B. Henderson

Introduction

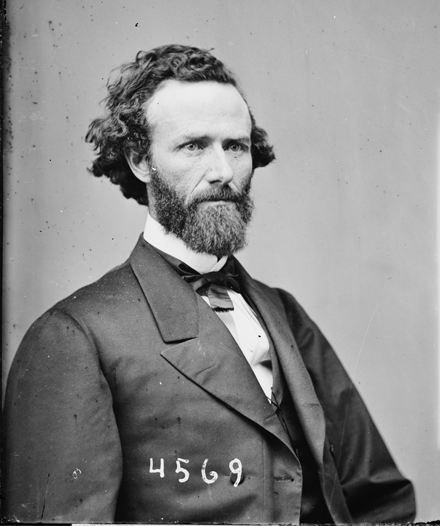

John B. Henderson represented Missouri as a US senator during the Civil War. Henderson worked hard to keep Missouri in the Union by offering his moderate view in the debate over the emancipation of enslaved people. In the opening weeks of 1864, Henderson proposed a resolution to ban slavery in the United States. His resolution became the Thirteenth Amendment to the US Constitution.

Early Years and Education

John Brooks Henderson was born on November 16, 1824, in Pittsylvania County, Virginia, near the village of Danville. His parents were James and Jane Dawson Henderson. The Henderson family had trouble making a living as farmers, in part because they were not enslavers. Hoping to find greater success in the West, James moved his family to Lincoln County, Missouri, in 1832.

Unfortunately, both James and Jane died four years after their arrival. Their deaths left twelve-year-old John as the eldest of his surviving siblings. Records do not show who cared for the orphaned children, but the impoverished couple left a small estate to help with their support.

Despite his early setbacks, Henderson managed to obtain a modest education. In 1843, at the age of nineteen, he moved to Prairieville in Pike County, Missouri, to attend school. After a year of formal studying, his instructor, Samuel F. Murray, encouraged Henderson to take up teaching. Teaching school in Prairieville left John with enough free time to study law. After three years of reading legal texts, he passed the bar exam and began work as a lawyer in Clarksville, Missouri.

Entrance into Politics

Henderson entered Missouri politics almost immediately after he relocated to Clarksville. The twenty-three-year-old announced his candidacy for the position of Pike County clerk in 1847. Henderson dropped out of the race after a few months “in pure deference” to the “worthy men” of “advanced age and numerous wrinkles” who remained in the field. His humorous letter gave the young lawyer one last attack on his opponents. The experience positioned him to receive the nomination as the Democratic candidate for state representative from Pike County. The Whig Party in the county supported a candidate named William Penix. The Whigs argued that Henderson was too young and too poor to represent their county in the state capital. Henderson’s supporters replied that their candidate could not control his age, and that the suggestion that Henderson did not have enough property or wealth showed the Whigs wanted to exclude average people from political office. Henderson won the close election by thirty-seven votes and became the youngest legislator in Missouri’s General Assembly.

Once in office, Henderson offered a resolution that demonstrated his position on the expansion of slavery into new territories. He argued that the US Congress had no constitutional right to regulate slavery in US territories such as those just taken from Mexico in the Mexican War. Henderson insisted that under the terms established in the Missouri Compromise of 1820, only the residents of the territories could make that decision. Meanwhile, the discussion in the General Assembly about the expansion of slavery became more agitated. More radical pro-slavery members of the legislature wanted to disregard the geographic restriction agreed to in the Missouri Compromise and widen the territory in which slavery could be instituted.

Becoming Established

Henderson lost his seat in the General Assembly in the 1850 election as Whig candidates won many contests across the state. He took the time off as an opportunity to refocus on his legal career. During the next several years he practiced law in northeastern Missouri. Working as a lawyer helped him to make more political connections. He also became involved in numerous real-estate transactions. Henderson’s work during this time placed him in a better position financially than he had been when he began his political career.

In 1856 Henderson won a second term in the General Assembly. Because of his political experience, he believed that he was ready to move to the level of national politics. Attendees of the Democratic congressional convention of Missouri’s Second District agreed and made Henderson the party’s candidate for the district. In the 1860 congressional race, Henderson ran against abolition and the expansion of slavery in the territories. Henderson lost the election because the Democratic Party was divided on the issue of slavery.

Shifting Views on Emancipation

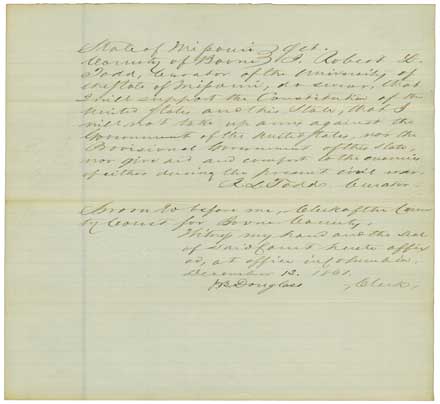

As the nation descended into division and civil war, politicians in Missouri had to decide which side of the conflict they would support. After a contentious convention to settle the question, leaders in Missouri opted to remain in the Union in 1861. Any state official who refused to take an oath of loyalty to the United States was removed from his position. US Senator Trusten Polk vacated his seat based on his sympathy for the secessionists of the South. Lieutenant Governor Willard Preble Hall appointed Henderson to serve the remainder of Polk’s term as senator in 1862.

Since Henderson was both a strong Unionist and an enslaver, he spent his first months in the Senate voicing his support for President Lincoln’s recommendation that emancipation be gradual and enslavers be compensated for their losses. After Congress passed a resolution in favor of compensated emancipation on April 10, 1862, Henderson traveled to Jefferson City to discuss the possibility of enacting the resolution in Missouri at the fourth session of the Missouri State Convention that summer. The senator urged the attendees to consider that the continuation of the war might force President Lincoln to “strike the final blow” to the Confederate and free enslaved people. Members of the convention, however, did not want to agitate the proceedings by discussing slavery.

Though his effort to have the state convention consider the idea of gradual emancipation initially failed, Henderson set out on a speaking tour to change public opinion in Missouri. Just a few months after his convention appeal, he told President Lincoln that “a great change is going on in the public mind in regard to this question.” Henderson’s analysis turned out to be correct. Missouri politicians in favor of emancipation won a majority of positions in the state elections of 1862.

Following the election, Henderson sponsored a new effort in the US Senate for compensated emancipation on December 9, 1862. His bill would pay enslavers in Missouri a total of $20 million to free the people they enslaved. But a Missouri congressman, John W. Noell, offered a competing bill. Noell wanted to provide only half of the amount that Henderson’s proposal offered. Henderson argued that Noell’s version would not be enough money to fully pay Missouri enslavers for their lost property. Neither bill earned enough support to pass during the session, ending the idea of compensated emancipation.

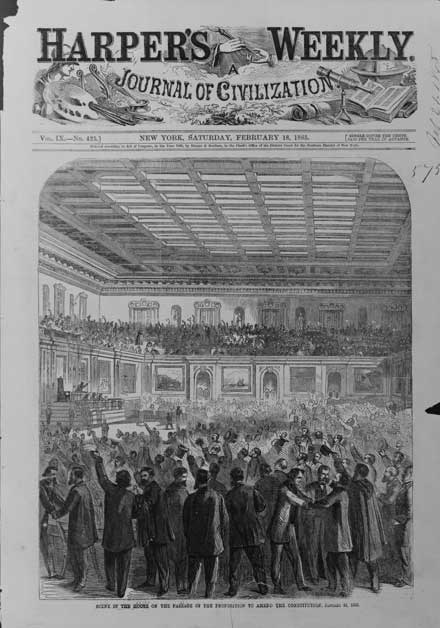

The Thirteenth Amendment

Henderson was selected for a full term as senator in November 1863. After he returned to Washington, he announced that he planned to propose a constitutional amendment that would emancipate all enslaved people. On January 11, 1864, Henderson presented Senate Joint Resolution 16 to abolish slavery in the United States. Senators Charles Sumner and Lyman Trumbull offered slightly different proposals to achieve the same purpose. All three agreed that slavery had to be immediately ended. The Senate passed an emancipation resolution after considerable debate on April 9, 1864. Just a few months later the House of Representatives cast their votes. Though a majority supported it, the vote fell short of the two-thirds margin required to pass an amendment. Six months later, on January 31, 1865, the votes were in hand, and the House passed The Thirteenth Amendment. After President Lincoln signed the bill, the amendment went to the states for ratification. Secretary of State William Seward announced on December 18, 1865, that the necessary three-fourths of state legislatures had ratified the Thirteenth Amendment. Slavery was now prohibited by the US Constitution.

Life after the Civil War

Henderson finished his term as a senator in 1869. He failed to win reelection and returned to Missouri. In 1876 Henderson served as the special prosecutor in the corruption trial known as the Whiskey Ring. The trial was held in St. Louis. His aggressive handling of the case threatened President Ulysses S. Grant’s administration. Henderson found connections between Grant’s personal secretary and the corruption in St. Louis.

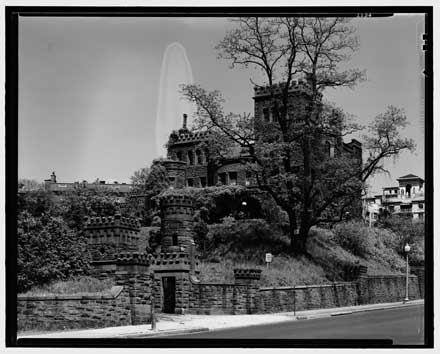

Henderson moved back to Washington during the late 1880s and lived in a large mansion at the corner of Florida and Sixteenth Streets that was called Henderson’s Castle. He remained active in Republican politics until his death on April 12, 1913.

Legacy

At the outset of the Civil War, John B. Henderson helped prevent Missouri from seceding from the Union. During his time as a senator, he tried to represent the views of conservative Unionists in his state. Over the course of the war, Henderson modified his position on emancipation to better reflect his constituents’ views. By 1864 the enslaving politician had written the original draft of the amendment that ended the institution of slavery in the United States. His moderate representation in a time of national crisis helped Missouri navigate the war.

Text and research by Zachary Dowdle

References and Resources

For more information about John Brooks Henderson’s life and career, see the following resources:

Society Resources

The following is a selected list of books, articles, and manuscripts about John B. Henderson in the research centers of The State Historical Society of Missouri. The Society’s call numbers follow the citations in brackets.

Articles from the Missouri Historical Review

- Guese, Lucius E. “St. Louis and the Great Whiskey Ring.” v. 36, no. 2 (January 1942), pp. 160-183.

- Sampson, F. A. “Hon. John Brooks Henderson.” v. 7, no. 4 (July 1913), pp. 237-241.

Articles from the Newspaper Collection

- “Henderson Burial Set for Tuesday.” St. Louis Globe-Democrat. April 14, 1913. p. 4. [Reel # 39651]

- “Keep it Before the People!” Bowling Green Democratic Banner. July 24, 1848. p. 2. [Reel # 27125]

- “Letter from Mr. Henderson.” Bowling Green Democratic Banner. July 30, 1849. p. 2, c. 2-5. [Reel # 27125]

- “Missourian Gone.” Clarksville Banner-Sentinel. April 16, 1913. p. 2. [Reel # 6663]

Books and Articles

- Christensen, Lawrence O., William E. Foley, Gary R. Kremer, and Kenneth H. Winn, eds. Dictionary of Missouri Biography. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1999. pp. 393-394. [REF F508 D561]

Manuscript Collection

- Henderson, John Brooks (1826-1913), Letter, 1870 (C0516)

The collection contains a single letter from Henderson to John T. Hoffman asking to be appointed as a delegate to the Liberal Republican convention in Cincinnati. Also includes a photograph of Henderson. - Rollins, James S. (1812-1888), Papers, 1546-1968 (C1026)

Includes several letters written by Henderson to James Sidney Rollins on national and state-level political matters during and after the Civil War.

Outside Resources

These links, which open in another window, will take you outside the Society’s website. The Society is not responsible for the content of the following websites:

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress

Several letters written by Henderson to President Lincoln during the Civil War on Missouri and national political issues have been digitized and can be found on this website.