Harriet Robinson Scott

Introduction

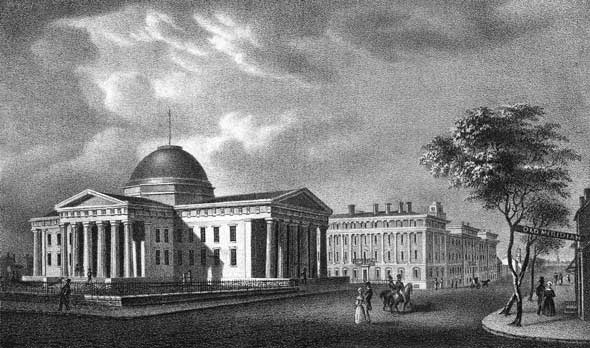

Harriet Robinson Scott was an enslaved woman who tried for more than a decade to gain her freedom through the court system. In separate cases that were later combined, Harriet Scott and her husband, Dred, sued for their freedom before several courts in Missouri. Their case eventually reached the U.S. Supreme Court in Washington, DC. It is one of the most important cases ever tried in the United States.

Early Years

Harriet Robinson was born into slavery in Virginia around 1815. She was enslaved by Major Lawrence Taliaferro (pronounced “Tolliver”) who served as a federal Indian agent. Major Taliaferro, a Virginian, was assigned to Fort Snelling around 1820 and served there for almost twenty years. Fort Snelling was a military fort and fur-trading outpost on the upper Mississippi River in present-day Minnesota. Taliaferro was a strong protector of Native American rights.

When Harriet Robinson was a teenager, she left Virginia, never to return. Major Taliaferro brought her with him to Fort Snelling in the early 1830s. He had his own dwelling at the fort and needed Harriet to work as his house servant. Though slavery was not officially allowed in this part of the United States as outlined in the 1820 Missouri Compromise, many members of the military kept enslaved people as they moved from one post to another, or went back and forth between a fort and their homes in other states.

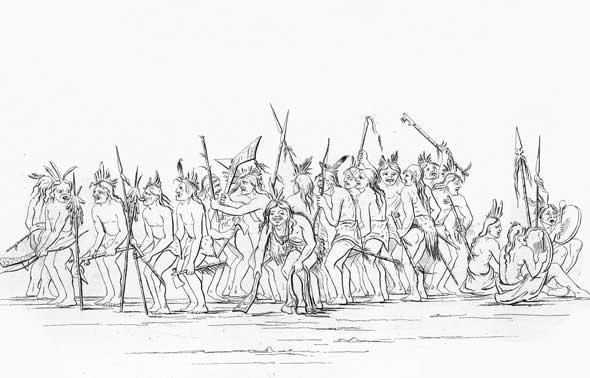

Harriet Robinson probably lived with many other enslaved people at Fort Snelling. She may have known an enslaved woman named Rachel who lived at Fort Snelling from about 1830 to 1834. Rachel would also later sue for her freedom in the Missouri courts in St. Louis. She based her claim on the argument that living in a free territory while at Fort Snelling had made her a free woman. In addition to working alongside other people of African descent, Harriet would have also been in contact with European fur traders and Native Americans, especially the Sioux and Ojibwe or Chippewa.

A Husband and a New Owner for Harriet

In May 1836, Harriet’s future husband arrived at Fort Snelling. Dred Scott worked as the personal servant or valet of his owner, Dr. John Emerson, a military surgeon. At that time, Harriet was about twenty-one years old, and Dred was probably thirty-six. Harriet and Dred must have met and formed a close relationship early on for in either 1836 or 1837, they were married in a civil ceremony performed by Major Taliaferro, who was a justice of the peace. At this point in her life, Harriet Robinson not only became Harriet Scott, the wife of Dred Scott, but she also became the property of Dr. Emerson. Some sources suggest that Major Taliaferro sold Harriet to Dr. Emerson and married her to Dred Scott so that the couple could remain together.

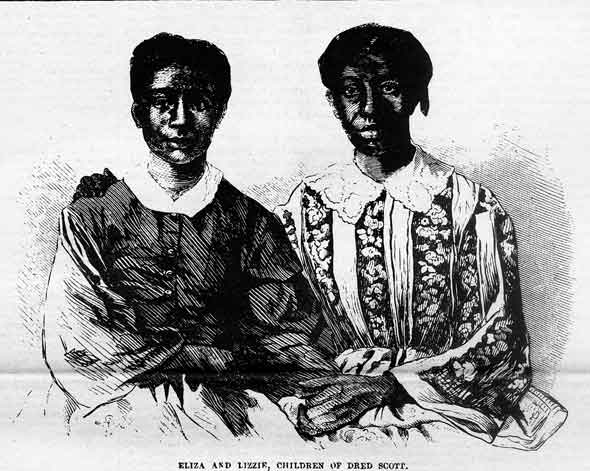

By April 1838, Harriet Scott was pregnant. Despite her condition, she had to leave Fort Snelling that month, perhaps for the first time since her arrival. Dr. Emerson had been transferred to Fort Jesup, Louisiana, and had requested that Dred and Harriet join him and his new wife, Eliza Irene Sanford. Harriet made the long journey to Louisiana but did not stay there long. By September, Harriet was almost full term and found herself in St. Louis. By October, she was heading north once again to Fort Snelling. On the way, Harriet gave birth in free territory to her first daughter, Eliza Scott, on the steamer, Gipsey. Once back at Fort Snelling, Harriet stayed there, nursing her baby and attending to Mrs. Emerson’s needs, for another two years.

Leaving Free Territory

During the summer of 1840, Harriet left Fort Snelling forever. Dr. Emerson had been transferred yet again, this time to Florida where the Seminole War was being fought. Harriet and her family were sent to St. Louis where they were hired out to work for other people while the Emersons collected their wages. Harriet gave birth to another daughter, Lizzie Scott, during this period of time. She most likely worked as a laundress and domestic servant. She probably worked long hours in her employer’s house, lived in quarters off the kitchen, cared for her children, but never collected any pay.

In 1843, Dr. Emerson suddenly died, leaving Harriet, Dred, Eliza, and Lizzie in the hands of his widow, Irene Emerson. Neither Harriet nor Dred appeared in Dr. Emerson’s will. After her husband’s death, Irene Emerson moved in with her proslavery father, Alexander Sanford, on his plantation in north St. Louis County. For the next three years, Harriet and Dred worked for other people while Mrs. Emerson collected their wages.

Filing a Suit for Freedom

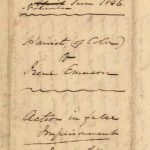

In the spring of 1846, Harriet Robinson Scott took legal action to claim her freedom. On April 6, 1846, Harriet and Dred Scott each filed separate petitions in the St. Louis Circuit Court to gain their freedom from Irene Emerson. Their lawyer was Francis Murdock.

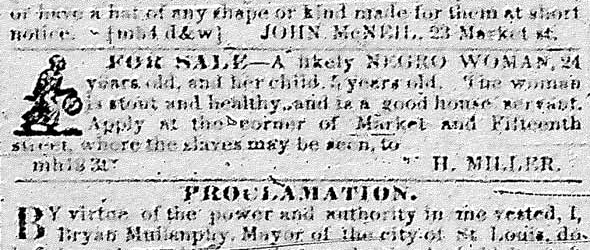

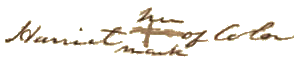

Unable to read or write, Harriet perhaps relied on advice from John R. Anderson, the minister of the Second African Baptist Church she attended in St. Louis. Harriet had learned about or knew personally other enslaved people who had filed lawsuits in Missouri courts. Many enslaved people were granted freedom if they had lived in free states with their owners’ permission or knowledge. Harriet had a good chance for freedom because of the many years she had lived at Fort Snelling. Harriet was helped legally and financially by the family and friends of Dred’s former enslaver, Peter Blow. Their cases came to trial on June 30, 1847, but were dismissed on a technicality. Their lawyer moved for a new trial.

Before the retrial took place, Irene Emerson made arrangements for the Scotts to be under the charge, or custody, of the sheriff of St. Louis County. For nine years, from March 17, 1848, until March 18, 1857, Harriet and her family remained in the custody of the sheriff. He was responsible for hiring them out and collecting and keeping their wages until the freedom suit was resolved.

It took two years for Harriet’s case to come to trial again. The delays were due to heavy court schedules, a tremendous fire in St. Louis on May 2, 1849, and an outbreak of cholera that followed the fire. Finally, on January 12, 1850, the case was heard, and the jury ruled in favor of the Scotts. Harriet and her family were free. This freedom, however, proved to be short lived.

A Long and Drawn Out Battle

The court’s decision did not please Mrs. Emerson and her brother, John F. A. Sanford, who had been handling her legal affairs since her husband’s death. Enslaved people were valuable property, and she did not want to lose Harriet, Dred, and their daughters and the income they provided her. Mrs. Emerson’s lawyers appealed her case to the Missouri Supreme Court. Before it came to trial, however, a decision was made to combine Harriet’s case with Dred’s. On February 12, 1850, the case was retitled Dred Scott v. Irene Emerson. The outcome of this case would also apply to Harriet and her daughters. Though her name disappeared from the trial title, Harriet’s desire for freedom did not cease. She would have to wait another two years for the trial to take place.

Meanwhile, Mrs. Emerson left St. Louis and moved to Springfield, Massachusetts. There she met Dr. Calvin Clifford Chaffee, an antislavery congressman from Massachusetts. They married in November 1850. Dr. Chaffee was unaware of his new wife’s court case involving the Scotts. In fact, he claimed later that he didn’t know that she was an enslaver. Mrs. Chaffee had handed the case over to her brother. On March 22, 1852, the Missouri Supreme Court reversed the earlier ruling, rejecting the Scotts’ plea for freedom. Tensions over the issue of slavery were rising throughout the county. The highest court in Missouri, in this decision, upheld the rights of enslavers over the rights of enslaved people.

A Refusal to Give Up

Harriet and Dred did not give up. Records show that Charles Edmund LaBeaume, a friend and supporter of the Scotts, hired Harriet from the sheriff on April 26, 1852. She worked for him for $4.00 a month, wages she never collected. Dred also worked for him for $5.00 a month. With the continued help of the Blow family and other supporters, the Scotts eventually took their case as far as the U.S. Supreme Court in what became the famous Dred Scott v. Sanford case.

Five years later, after moving the case through the Missouri courts to the highest court in the nation, Harriet finally received a decision about her suit for freedom. On March 6, 1857, the court ruled that Harriet, Dred, Eliza, and Lizzie Scott should remain enslaved. Just after the decision, John Sanford died, and Calvin Chaffee insisted that his wife transfer ownership of the Scotts to Taylor Blow. Blow then freed Harriet and her family on May 26, 1857, in St. Louis in the courthouse and before the same judge who had heard the first case. Mrs. Chaffee insisted on collecting the back wages held by the sheriff. They amounted to about $750.

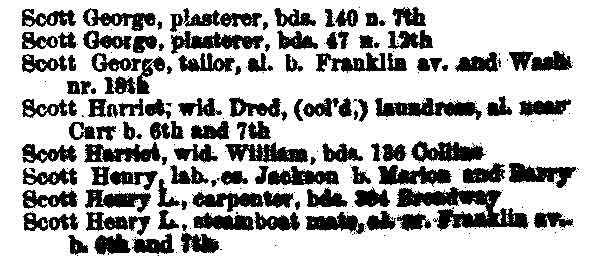

Just one year later, Harriet’s husband died of tuberculosis. Though Dred did not live to enjoy his freedom for long, Harriet worked as a “free Negro” laundress in St. Louis for many years. Her name is listed in St. Louis directories from 1859 to 1876. She is also listed in the 1860 census as living in her own home and in the 1870 census as a live-in domestic. Harriet Scott, a free woman, died of “general disability” at age sixty-one on June 17, 1876. She was buried in Greenwood Cemetery, a burial ground in St. Louis for Black Americans.

Legacy

Harriet Robinson Scott could not have known that her legal fight for freedom, first started when she was about thirty in 1846, would eventually contribute to civil war and the end of slavery in America. Her decision to file a suit for freedom and to stay with it until its final conclusion were acts of high courage and determination. These traits would give strength to the long and difficult struggle for civil rights that Harriet Robinson Scott’s descendants would endure for the next hundred years.

Text and research by Carlynn Trout

References and Resources

For more information about Harriet Robinson Scott’s life and career, see the following resources:

Society Resources

The following is a selected list of books, articles, and manuscripts about Harriet Robinson Scott in the research centers of The State Historical Society of Missouri. The Society’s call numbers follow the citations in brackets.

Articles from the Newspaper Collection

- “Finding a St. Louis Legend.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. March 5, 2006. pp. 1-2C.

- “Genealogist Fills in Gaps in Scott’s Story.” Columbia Daily Tribune. March 9, 2006. p. 8A. [Reel # 8752]

- “One Man’s Case and How It Changed a Nation.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. March 4, 2007. p. B1.

- “The Seed of Freedom and Justice for All was Planted Here.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. March 7, 2007. p. B1.

- “150th Anniversary.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. March 2, 2008. p. 11D.

Books and Articles

- Corbett, Katharine T. In Her Place: A Guide to St. Louis Women’s History. St. Louis: Missouri Historical Society Press, 1999. pp. 60-62. [REF H235.47 C81]

- Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. June 27, 1857, pp. 1-2. [REF IHG 973.7 L565 oversize]

- Hess, Jeffrey A. “Dred Scott: From Fort Snelling to Freedom.” Historic Fort Snelling Chronicles. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society. no. 2, 1975. [REF Vertical File: Dred Scott]

- James, Edward T.,et al., eds. Notable American Women, 1607-1950; A Biographical Dictionary. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1971. v. 1, pp. 181-183. [REF 920 N843 v.1]

- St. Louis City Directory. 1859 [REF H235.36 K386 1859 In Case]

- Swain, Gwenyth. Dred and Harriet Scott: A Family’s Struggle for Freedom. St. Paul: Borealis Books, 2004. [REF F552 Sw14]

- Trout, Carlynn. Notable Women of Missouri. Columbia, MO: Columbia, Missouri Branch of the American Association of University Women. Columbia, MO, 2005. [REF F508 T758 2005]

- van Ravenswaay, Charles. Saint Louis: An Informal History of the City and Its People, 1764-1865. St. Louis: Missouri Historical Society Press, 1991. [REF H235.47 V35]

Outside Resources

- Africans in America PBS Series

Based on the PBS series Africans in America, this website tells the story of Dred Scott’s life and legal battle. - The Dred Scott Case

Hosted by the National Park Service, this website on the Old Courthouse in St. Louis provides information about one of its historic trials, the Dred Scott Case. - Historic Fort Snelling

This website, offered by the Minnesota Historical Society, presents rich textual and visual information on the history and importance of Fort Snelling. - Missouri State Archives: Dred Scott: 150th Anniversary Commemoration

This Secretary of State Website offers a thorough study of the Dred Scott case as it moved through the Missouri court system and ended in the U.S. Supreme Court. Also of great interest is the link “Conservation of the Dred Scott Papers,” which shows how the State Archives restored and preserved the original court records of this case. - The Revised Dred Scott Case Collection

This comprehensive Website provides images of the actual case documentation, including petitions to the courts, writs of summons, appeals, and affidavits. A chronology of events is also included.